By John Harrison, Loughborough University, UK.

Why think big?

Here is the big paradox of academic research. Everything you read or hear as an early career researcher tells you that your research must involve ‘thinking big’. If you don’t believe me, read any journal website of your choice. The language will tell you something akin to only “the very best scholarship”, research which makes “a substantial theoretical, conceptual or empirical contribution to the advancement of understanding”, and article’s which are capable of “stimulating and shaping research agendas” will be published. What none of this tells you is that most research only sets out and achieves to make a small, incremental contribution to knowledge. This is perfectly fine. Indeed, it is to be expected. I would go so far as to say that >99.9% of published research falls into this category of making a small, albeit important, contribution to knowledge. So, what is going on here? Why does this paradox exist? And importantly, how do researchers make their way in this landscape?

Research and academic publishing takes place in a competitive environment. Journals, editors, and publishers are under pressure to attract the best research and this is reflected in the phrasing which appears on their websites. Your employer wants (and increasingly mandates and incentivises) you to only publish the best research, in the best journals, and generate the biggest impact. And let’s be honest here, research is a big investment of our time and effort, meaning it is only natural that at the end of it we want our ideas to be recognised as making an important contribution.

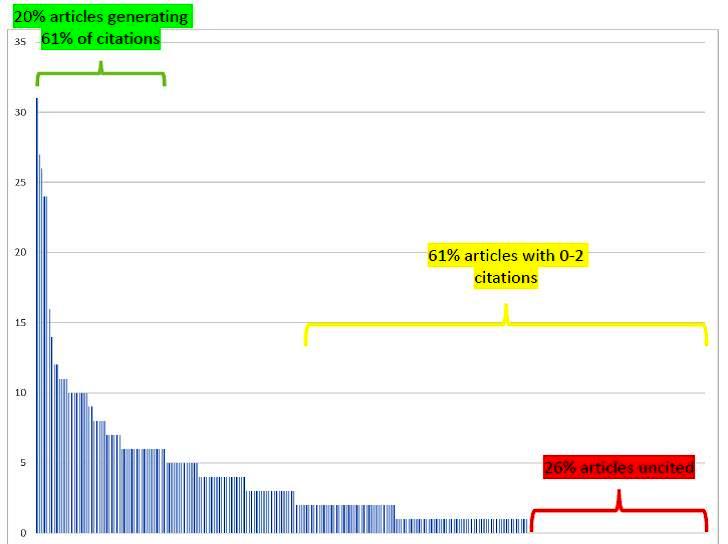

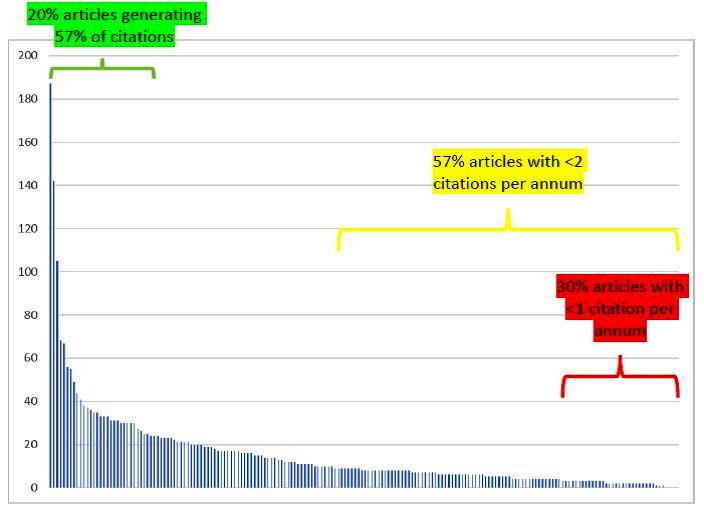

While estimates vary there is no denying that a lot of published research goes under the radar (Remler, 2016). Here is an example from a recognised journal in our field. Figure 1 presents the number of times research articles published in 2016 or 2017 were cited at the time of writing (August 2018). This is a useful indicator of (i) how quickly some research is picked up, and (ii) how very few papers are often doing the work to generate a journal’s impact factor. Now look at Figure 2. This presents the number of times research articles published in 2012 or 2013 (c. 5 years ago) were cited at the time of writing. What can we learn from this? For many years I worked with a notional 80/20 rule in my head. Although not quite backed up by the data in the two graphs below, the sentiment remains the same. When I first looked at this in 2009-10, across 5 journals in our field, 80% of citations contributing to those journal’s impact factor (calculated as the number of citations to articles published in the two previous years, divided by the number of published articles, to produce a figure which is the number of citations the “average article” in that journal will generate) were generated by only 20% of articles. This meant that the vast majority of articles (c. 80%) were only contributing 20% of the citations. You could argue they were going unnoticed.

Figure 1: Citations for papers published in 2016-2017 (Source: Web of Science)

Figure 2: 5-year citations for papers published in 2012-2013 (Source: Web of Science)

As an early career researcher, what I took from this was that “getting published” is great but it is not enough. There is a threshold to getting published (what it takes to get your writing through the peer-review process) but there is another threshold to getting it noticed. This is why you need to ‘think big’.

So where do you start …?

Constructing key research ideas

It all starts at the beginning. In a recent RSA blog I suggested we need to Stop! Look! Listen! Think! if we are to extend our research horizons. This applies to all researchers, but it was borne out of reflecting on the transition from early career researcher and some of the conscious decisions I took around 4-5 years post-PhD. For me, this was a crucial time. Immediately post-PhD, my publications were on two topics (new regionalism, English regionalism) which had been extensively researched for 5-10 years. Everything that needed to be written had already been written (by others). So, when embarking on a research project my advice is to ask yourself two key questions:

- What do we know?

- What should we know that we don’t know?

In my case, looking back I can see the answers in the first part of my “early career” were (i) an awful lot, and (ii) arguably very little!!

But it is not all doom and gloom. This is to be expected coming out of a PhD. What comes next is the important part.

Looking back to the second part of my “early career” stage (2007-2010), I can see how the answers to these two questions began to change. My research began to move away from where the debate was 5-10 years ago and started to engage with where regional debate were today. In my case this was the new city-regionalism.

Try thinking of it like a wave. When I published my first papers on the new regionalism and English regionalism the wave had already gone. I was somewhere marooned in the backwaters. This time I felt like I was on the wave, part of the debate.

And then it came together. I distinctly remember reading a 2009 editorial by Neil Wrigley and Henry Overman in the Journal of Economic Geography where they talked about ripple-, wave- and splash-making papers. Writing in the context of the 10th anniversary of the journal, they identified ripple-making papers as those with 10 or more cites, wave-making papers as those with 40 or more cites, and splash-making papers being those with 60 or more cites. This perked my interest in understanding what it took to produce research of this type. It is where the 80/20 mantra became important for me because not only did I want to get my research published (the goal of any early career researcher) it gave me a new goal: to get my research in to the 20% of papers published in each journal each year which are the ripple-, wave- and splash-making papers.

For people coming out of “early career”, as I was, this is key because up to that point I don’t ever remember consciously looking and wondering about the bigger picture. I was not ‘thinking big’. It was only then that I first seriously considered the questions of “What do we know?” and “What should we know that we don’t know?”. Or to finish off the analogy, what does it take to start a wave, to set the agenda.

But let’s not get carried away. There is a balance to be had after all …

Defending key research ideas

Here it is in a nutshell: don’t oversell, don’t undersell, be realistic. This is important because having read the previous section and hearing all this talk of ‘thinking big’, you might be tempted into thinking that to get noticed your research has to revolutionise regional thinking and debate. Remember, most research only sets out and achieves to make a small, incremental contribution to advancing regional debate. Indeed, many ripple-, wave-, splash-making articles result not because the author/s set out to achieve this, but through a combination of factors many of which are often outside their control.

So, what can you do as a researcher?

Don’t oversell: remember, before your research is published it will go through peer-review. As a journal editor and regular peer-reviewer I have to say that overselling is much less common than underselling, but all the same it is important to remember that any claims you make must stand up in the face of scrutiny.

Don’t undersell: this is much more common, particularly among early career researchers. Think of it as addressing the “so what” question? You cannot assume readers will be interested in your research or that they will read it and automatically work out what they are meant to do with it. Help them. Reach out to them. Tell them why your interest in this research could/should be of interest to them and their research.

But be careful. This is all a balancing act. ‘Thinking big’ is not found in statements of grandeur dripping with boosterist language. It may sound surprising but ‘thinking big’ is about research which recognises its own self-importance. In other words, it addresses the “so what” question. It does tell the reader why it is original, why it is significant, and these claims stands up to scrutiny i.e. they can be defended.

Advertising key research ideas

Can you still publish and perish? Well, in short, yes. The still oft heard “publish or perish” mantra is to my mind completely redundant in academia today. This is why advertising your key research ideas is so important. Let’s look at three approaches which as researchers we can look to control.

As outlined the first part to advertising your key research ideas is to remember that it is not simply enough to say, “I set out to research this, this is how I did it, this is what I found”. Research that gets noticed does much more than this. It reaches out and engages its intended audience. It says to readers “Here is a significant issue of broad relevance, this is my contribution that represents new knowledge and deepens understanding, this is why it should be of interest to you”.

This is great but how do people find your research in the first place?

The second part to this revolves around advertising in the classical sense. The economist John Kenneth Galbraith famously outlined in his 1958 book The Affluent Society how the function of advertising is to “create desires – to bring into being wants that previously did not exist”. This is as true for advertising a new academic paper as it is advertising a new product. Advertisers place adverts where they know their intended audience will likely see it. The equivalent for research is choosing the journal where the audience you want to find your work will most likely see it.

Finally, the third part. Seeing the advert or article is one thing but there is no guarantee that once they have seen it, they will “want” to buy it or in our case read and engage with it. It most cases seeing it will involve a split-second look at the title and an instant decision whether to take a second look or move on. Therefore, the title, and then the abstract, is so important to get right. Titles and abstracts are what advertise your research ideas. Their function is creating the desire among readers, to make readers want to read something that before they saw it they previously did not know existed. You can read more on what makes good and bad titles and abstracts here, but my advice is to think of the title like a newspaper headline. The title needs to be eye-catching. It needs to make your research ‘visible’ in the first place and make people stick around long enough to read the abstract. The abstract must then convince the reader that this is a ‘quality’ piece of research such that investing the time to read it will pay-off. What this means is returning to those two key questions that we started with: “What do we know?” and “What should we know that we don’t know?” A good abstract will tell the reader this and one more thing: how your research which is being presented in the article advances regional thinking and regional debate.

Go on, give it a go!

John Harrison is Reader in Human Geography at Loughborough University, UK. He is editor of the Urban and Regional Horizons section of Regional Studies. This article is based on a presentation delivered at the 2017 RSA Student and Early Career Conference in Newcastle. You can follow him on twitter @DrJWHarrison.