By Dr Christina Wolf (E-mail), University of Hertfordshire, UK

This article examines how the presence or absence of locally rooted anchor firms shapes regional resilience, drawing on evidence from East Germany’s post-reunification experience. The piece highlights how rebuilding anchoring functions can help “unmake” uneven development and support place-based regional transformation.

Reference to the original article:

Christina Wolf (2025). The making and unmaking of uneven development: the role of anchor firms in creating and overcoming industrial decline in East Germany, Journal of Economic Geography, 2025; https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbaf055

Revisiting development traps through anchor firms

Gaps between prosperous and “left-behind” regions continue to widen across Europe and other advanced economies. Spanning inequalities in income, wealth, foundational services, and overall well-being, and they fuel powerful emotional geographies—fear, loss, and betrayal—that increasingly feed into populist politics. Understanding the mechanisms that reproduce such uneven development has therefore become an urgent scholarly and political priority.

My research shows that uneven development is reproduced through the way industrial ecosystems are either anchored by – or cut off from – large, locally rooted firms that control key technologies. Regions that host such anchor firms become hubs of high value-added activity, innovation, and dense supplier networks. Those that do not risk becoming mere extended workbenches in someone else’s value chain, exposed to a drain in productive capabilities. This reveals a critical policy lever for addressing regional inequality: (re)creating anchor firm functions in peripheral regions.

What are anchor firms?

Anchor firms are large, regionally headquartered companies in proprietary control of key technologies. They act as agglomerating forces that shape the market expansion and technological trajectories of their suppliers and complementors (Feldman, 2003). Their presence – or absence – structures regional hierarchies of value creation in two main ways. First, by concentrating strategic decision-making and high-value technological activities near their headquarters while relegating routine production to branch plants, anchor firms generate a spatial differentiation of value addition. This produces uneven job types, income, wealth, and social status, and renders peripheral regions dependent on external headquarters for investment and technology. Second, where anchor firms are absent, regions face persistent losses of productive capabilities, as highly skilled labour and innovative firms tend to cluster in close proximity to anchor firms.

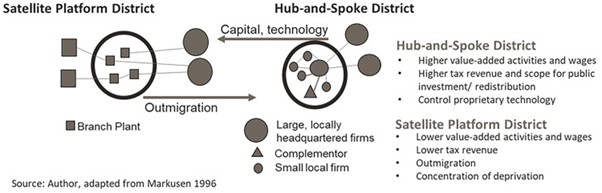

These dynamics point toward a broader conceptual distinction. Core regions form Hub-and-Spoke districts, where large, locally headquartered anchor firms organise and sustain surrounding smaller firms in spatial proximity. By contrast, peripheral regions resemble Satellite Platform districts, in which firms are connected to anchor firms as branch/ assembly plants or distant suppliers (Figure 1).

The making of uneven development: how anchor firms were dismantled in East Germany

East Germany after reunification is a critical case which illustrates these dynamics. More than three decades on, the East–West divide remains stark, despite massive fiscal transfers, estimated at up to €3.4 trillion. Using historical process tracing and spatial analysis, the article unpacks this conundrum.

Experiencing one of the most severe episodes of deindustrialisation in post-war Europe, it has seen a profound restructuring of regional productive ecosystems. The Treuhandanstalt pursued a rapid, neoliberal-era privatisation strategy, selling most East German firms directly to West German competitors. Implementing this approach required dismantling the socialist-era combines that had previously served as regional anchor firms. Their profitable divisions were absorbed into West German headquartered parent companies, while remaining sites became low-value branch plants or closed altogether. The result was a profound deindustrialisation shock, with nearly 90% of manufacturing jobs lost in a timespan of just three years, and the reclassification of much of the East as a ‘Satellite Platform’.

A telling example is Rudolstadt’s former X-ray technology cluster. Once a hub for X-ray technology development that coordinated a network of specialised regional suppliers, the site was reduced to an end-assembly location after its acquisition by Siemens. Engineers departed, supplier networks collapsed, and what had been an integrated ecosystem lost its technological core.

The long shadow of “neoliberal shock therapy”

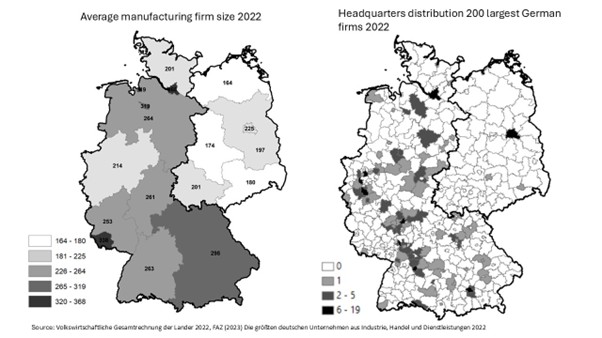

To this day, East German regional economies are dominated by small manufacturing firms lacking local anchors as shown below in the distribution of headquarters of Germany’s 200 largest firms.

Spatial analysis confirms that East German districts continue to lag in manufacturing intensity, research and development, and high-tech employment.

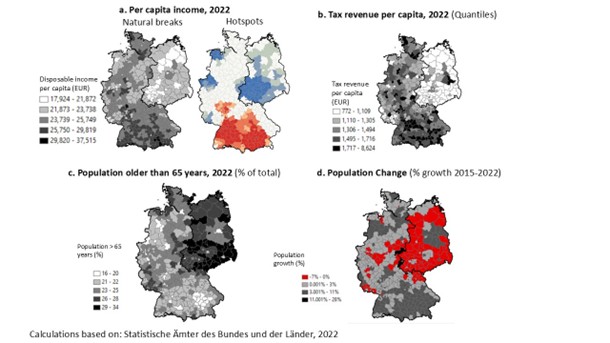

The absence of local anchors leaves East German productive ecosystems highly vulnerable to Myrdalian ‘backwash effects’: low wages and job growth prompting outmigration, shrinking the tax base, eroding public services and a deep sense of political and emotional marginalisation.

Unmaking uneven development: Anchor firms in Jena’s revival

Yet the East German experience demonstrates not only the destructive consequences of dismantling anchor firms, but also the developmental potential of strategically rebuilding and nurturing them. The industrial recovery of the opto-electronics cluster around Jena demonstrates how reconstituting anchor processes can help ‘unmake’ uneven development.

Jena’s modern opto-electronics and medical-technology clusters build on an industrial base created by the Carl Zeiss companies. Founded and developed in Jena, these foundation-owned firms and their close scientific partnerships made the city the historic core of Germany’s precision-optics industry. After 1945, Zeiss and Schott were split into East and West entities. At reunification, the East German VEB Carl Zeiss Jena was broken up and strategic control shifted to West German headquarters in Oberkochen and Mainz, triggering major job losses and contributing to wider economic decline in southern and eastern Thuringia.

The decline of the Jena site itself was averted by preserving and rebuilding capabilities through Jenoptik, retained under Thuringian ownership, which attracted investors, acquired firms while relocating their headquarters to Jena, and fostered dense industry networks alongside strong public research institutes. Zeiss later consolidated its medical-technology division in Jena, creating Zeiss Meditec and expanding through strategic acquisitions. Today, Jenoptik, Zeiss Meditec, and Schott function as anchor firms whose state and foundation-based ownership structures channel agglomeration gains back into local capabilities.

Lessons for left-behind regions

The East German experience highlights a powerful lesson: regional inequality is shaped by how economies are organised and who controls their productive assets. This insight can be mobilised as a policy lever for addressing regional inequality.

Policy approaches to regional polarisation typically fall into two camps: place-based approaches that rebuild a sense of belonging by restoring the foundational economy (MacKinnon et al., 2022), and place-sensitive, growth-oriented approaches that address market failures in the diffusion of agglomeration economies (Iammarino et al., 2019; Rodríguez-Pose, Bartalucci, et al., 2024). It is important for these two approaches to work well together.

A critical policy lever to create an economically dynamic and sticky productive ecosystem lies in the (re)creation of anchor firm functions. This does not mean reviving old-style conglomerates. Modern anchor firms can emerge from state-backed initiatives, university spin-offs, or cooperative ownership models, especially if tied to mission-oriented policies supporting the green and digital transitions. The double challenge is nurturing regionally headquartered anchor firms capable of developing dynamic technological capabilities, while simultaneously curbing the potential monopolising and rentierist tendencies of such firms. Without effective nurturing of anchoring processes, efforts to address market failures, such as improving connectivity or workforce skills, risk exacerbating outmigration rather than generating locally rooted development.

References

Feldman, M. (2003). The locational dynamics of the US biotech industry: Knowledge externalities and the anchor firm hypothesis. Industry and Innovation, 10(3), 311–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/1366271032000141661

Iammarino, S., Rodriguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2019). Regional inequality in Europe: Evidence, theory and policy implications. Journal of Economic Geography, 19(2), 273–298. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lby021

MacKinnon, D., Kempton, L., O’Brien, P., Ormerod, E., Pike, A., & Tomaney, J. (2022). Reframing urban and regional ‘development’ for ‘left behind’ places. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 15(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsab034

Rodríguez-Pose, A., Bartalucci, F., Lozano-Gracia, N., & Dávalos, M. (2024). Overcoming Left-Behindedness Moving beyond the Efficiency versus Equity Debate in Territorial Development (No. Policy Research Working Paper 10734). World Bank.