By Ries Anderson (e-mail), Nancy Agyeman, Lord Kainyah, Richard David and Prof Dr Pablo Collazzo*, Business & Tourism Unit, Thomas More University of Applied Sciences, Belgium.

Introduction

When studying the microeconomics of competitiveness, we chose to focus on the Ghanaian cocoa cluster and the Flemish chocolate cluster due to their natural synergy. Our team, consisting of two Ghanaians and one Belgian, was well-equipped to explore this topic, as both clusters play essential roles in their respective economies and are deeply interconnected. Ghana is one of the world’s largest producers of cocoa beans, while Flanders excels in the production and export of premium chocolate. Through our research, we found that these clusters complement each other like puzzle pieces, creating a mutually beneficial relationship.

Improvements in one cluster typically benefit the other. For example, enhancing Ghana’s infrastructure and processing capabilities can lower costs for Flemish chocolate producers. In contrast, innovations in Belgian chocolate manufacturing can generate demand for higher-quality, ethically sourced cocoa from Ghana. At the macroeconomic level, both regions have shown resilience and growth.

Flanders benefits from advanced infrastructure, a skilled labour force, and high levels of research and development intensity. At the same time, Ghana capitalises on its abundant natural resources and efforts to attract foreign investment. However, both regions face challenges—Flanders must navigate sustainability and cost pressures, while Ghana grapples with infrastructure gaps and the need to add value.

By mapping these clusters and analysing them through Porter’s Diamond Model, we identified opportunities for synergy. Our recommendations emphasise fostering sustainable partnerships, investing in local processing in Ghana, and reducing the carbon footprint of cocoa supply chains. These steps will strengthen the relationship between Flanders and Ghana, ensuring shared growth and prosperity.

Microeconomics of Competitiveness and Cluster Policy

Porter’s Microeconomics of Competitiveness (1990; 2008) posits that national prosperity is grounded not in natural endowments or macroeconomic policy alone, but in the productivity of firms operating within competitive clusters. Clusters—geographically concentrated groups of interconnected firms, suppliers, and institutions—drive innovation, specialisation, and upgrading.

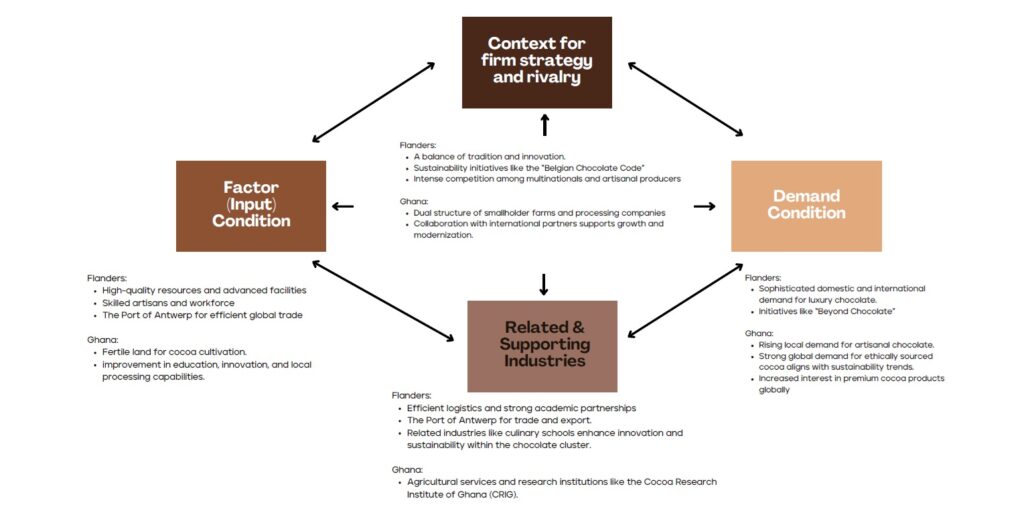

Porter’s Diamond Model identifies four interrelated determinants of national or regional competitiveness:

-

Factor conditions (infrastructure, skills, knowledge);

-

Demand conditions (sophisticated local markets);

-

Related and supporting industries; and

-

Firm strategy, structure, and rivalry.

These interact with government policy and have the chance to shape competitiveness outcomes. The model highlights how localised ecosystems—such as Flanders’ chocolate industry or Ghana’s cocoa sector—create and sustain competitive advantage.

Cluster policy, when effectively designed, stimulates collaboration between firms, academia, and public institutions, encouraging innovation and sustainable upgrading. In the Flemish–Ghanaian context, this means transforming a historically extractive relationship into a circular, knowledge-based partnership that enhances competitiveness in both regions.

Divergent Structures, Shared Dependencies

At the macro level, Flanders and Ghana represent two sides of the global value chain. Flanders, with a GDP growth rate averaging 1.7% from 2009 to 2022, benefits from advanced logistics, skilled labour, and high R&D intensity (National Bank of Belgium, 2024; Hanssens, 2022). Ghana, rebounding from fiscal challenges, achieved 5.9% growth in 2024, driven by industry and agriculture (IMF, 2024).

However, their microeconomic foundations reveal asymmetries. Flanders’ innovation-led economy invests 3.35% of GDP in R&D, exceeding EU targets. Ghana’s economy, which remains heavily reliant on raw commodity exports, faces challenges in local processing, infrastructure development, and the diffusion of technology (Strategy and Research Department, 2023).

Both regions demonstrate resilience: Flanders through high-value-added exports and Ghana through its diversification and growing participation in global supply chains. Yet, competitiveness remains unevenly distributed across the cocoa–chocolate value chain.

Porter’s Diamond Analysis

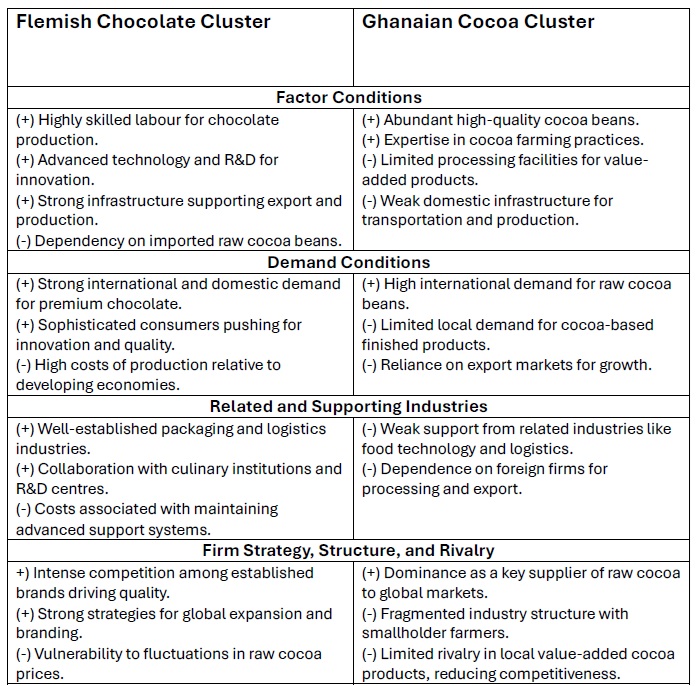

Factor Conditions

Flanders’ advanced infrastructure, research institutions, and skilled artisans underpin its innovation capacity (Ali & Ebers, 2015). Ghana’s factor advantages are primarily natural—fertile soils and experienced farmers—but are undercut by limited mechanisation and processing infrastructure. Bridging this gap requires investment in education, rural logistics, and technology transfer.

Demand Conditions

Belgian consumers are discerning, fostering innovation in flavour and sustainability—exemplified by initiatives like Beyond Chocolate, which ensures ethical sourcing. In Ghana, demand for locally processed cocoa is nascent but rising, offering scope for development of the domestic market (Food and Agricultural Commodity Systems, n.d.).

Related and Supporting Industries

Flanders’ cluster benefits from dense linkages with packaging, logistics, and academic partners, creating a dynamic ecosystem. Ghana’s supporting industries are weaker, though programs by the UNDP and EU seek to enhance agricultural services, traceability, and local processing (Agroberichten Buitenland, 2024).

Firm Strategy, Structure, and Rivalry

Flemish firms combine artisanal heritage with corporate scale, maintaining competitiveness through brand reputation and sustainability innovation. Ghana’s fragmented smallholder system limits rivalry and productivity upgrading, though emerging cooperatives and farmer associations are slowly changing this (International Trade Administration, 2023).

Figure 1: The Diamond Model of the Flemish and Ghanaian Clusters. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on desk research.

The Flemish Chocolate and Ghanaian Cocoa Clusters

Cluster History and Composition

Belgium’s chocolate-making tradition dates back to the 17th century and has evolved into a globally recognised symbol of quality. Flanders’ cluster comprises premium manufacturers, artisanal producers, and supporting institutions, such as the Chocolate Academy and the Port of Antwerp, a central logistics hub for cocoa imports (Toerisme Vlaanderen, n.d.).

Ghana’s cocoa industry began in the late 1800s and now supports the livelihoods of over 800,000 smallholder farmers. The Ghana Cocoa Board (COCOBOD) regulates the sector, while the Cocoa Research Institute of Ghana (CRIG) supports efforts to improve quality. However, the country still exports roughly 85% of its cocoa in raw form, limiting domestic value addition (UNDP, 2024).

Strengths and Weaknesses

| Cluster | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Flanders | • Strong reputation for high-quality chocolate and pralines (Visit Flanders). • Innovation-driven competition among firms. (Visit Flanders) • Excellent logistical infrastructure and strategic location in Europe (CHAN) • Rich history and expertise in chocolate-making (CHAN) | • Potential overreliance on traditional chocolate products. • Increasing competition from lower-cost producers. • Challenges in sustainable sourcing of cocoa beans. • Possible fragmentation among smaller producers. |

| Ghana | • Significant global market share in cocoa production. • Favourable climate for cocoa cultivation. • Government support through COCOBOD. • Growing focus on value addition and local chocolate production. | • Limited domestic chocolate manufacturing capacity. • Vulnerability to global cocoa price fluctuations. • Environmental concerns related to cocoa farming practices. • Need for improved infrastructure in rural cocoa-growing areas. |

These clusters are bound by interdependence: Ghana’s raw material supply fuels Flanders’ premium production, while Flanders’ innovations and demand patterns shape Ghana’s production practices.

Table 2: Comparative Advantages and Disadvantages identified in the Diamond Model. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on desk research.

Insights from Industry Experts**

Synergies

1. Local Value Addition in Ghana:

Encouraging domestic cocoa processing into cocoa mass and butter could increase Ghana’s income retention by up to 45%, reduce transportation emissions, and improve export competitiveness. This aligns with Porter’s view that upgrading along the value chain enhances regional productivity and shared prosperity.

2. Long-Term Buyer–Farmer Partnerships:

Flemish firms can establish guaranteed contracts with Ghanaian cooperatives, enabling farmers to secure loans and invest in equipment. This mirrors successful cluster policies that link SMEs and multinationals within shared innovation networks.

3. Sustainable Supply Chain Governance:

The EU’s Deforestation Regulation offers an opportunity to formalise traceability while supporting farmers’ compliance. Uniform sustainability standards across global markets would reduce regulatory asymmetries that currently disadvantage European firms (Interview, 2024).

4. Knowledge and Training Exchange:

Joint R&D programs between Flemish universities and Ghanaian institutions (e.g., CRIG) could accelerate technology transfer in post-harvest processing, digital traceability, and regenerative farming.

Policy Recommendations

A more inclusive and resilient cocoa–chocolate value chain demands coordinated policy action grounded in Porter’s Cluster Policy Framework:

-

Invest in Processing Infrastructure and Logistics:

Ghana’s government should prioritise agro-industrial zones and rural road networks to reduce transaction costs and foster local processing clusters. -

Foster Cross-Regional Cluster Cooperation:

The EU and African Union can institutionalise inter-cluster partnerships linking Flemish and Ghanaian actors in R&D, sustainability certification, and innovation funding. -

Empower Farmers through Fair-Trade Contracts:

Firms and policymakers should establish mechanisms to guarantee minimum farm-gate prices and income security, thereby mitigating volatility and enhancing livelihoods. -

Align Sustainability and Competitiveness Policies:

Environmental standards must not become trade barriers; instead, they should incentivise sustainable upgrading across the entire value chain. -

Encourage Circular and Carbon-Neutral Practices:

Investments in renewable energy for processing and reduced transport emissions will enhance both clusters’ environmental competitiveness.

Conclusion

The Flemish and Ghanaian clusters illustrate the duality of global competitiveness: advanced economies lead in innovation and branding, while developing economies provide essential raw materials yet remain locked in low-value activities. Applying Porter’s Microeconomics of Competitiveness reveals that prosperity grows not from isolation, but from mutual upgrading within interconnected clusters.

A forward-looking strategy should view cocoa not merely as a commodity, but as a shared regional asset capable of driving sustainable development, technological transfer, and cultural diplomacy between Africa and Europe. Aligning cluster policy with global sustainability goals will transform this interdependence into a model of inclusive competitiveness—one where value is created, retained, and distributed equitably across continents.

The ultimate measure of a region’s competitiveness will no longer be its isolated excellence, but the resilience and equity of the global partnerships it builds. Policy must therefore shift from simply fostering local clusters to actively architecting a more balanced and sustainable global economy.

References

Ali, M., & Ebers, E. (2015). The Belgian Chocolate Cluster: Building Competitiveness at the Regional and National Level.

Hanssens, J. (2022). STI in Flanders: Science, Technology & Innovation Policy.

Strategy and Research Department (2023). Cocoa Industry in Ghana.

UNDP (2024). Ghana Launches Initiative to Promote Sustainable Cocoa Production.

National Bank of Belgium (2024). Economic Review 2024.

Porter, M. (1990, 2008). The Competitive Advantage of Nations.

*Note

This article is a reflective summary of a comprehensive academic work titled “An integrated exploration of the Flemish chocolate cluster and the Ghanaian cocoa cluster“, developed by Nancy Agyemang, Ries Anderson, Lord Kainyah, and Richard David, under the supervision of Dr Eduardo Oliveira and Prof. Dr. Pablo Collazzo at the Business & Tourism Unit of Thomas More University of Applied Sciences, Mechelen, Belgium.

Professor Pablo Collazzo has been instrumental in introducing business schools worldwide to the MOC network and guiding them in implementing MOC classes and related research activities, including at Thomas More University of Applied Sciences. The Microeconomics of Competitiveness (MOC) course is a distinctive course platform developed at Harvard Business School by Professor Michael Porter and a team of colleagues at the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Dr Eduardo Oliveira (e-mail). The students’ work is available upon request from Dr Oliveira.

**The interviewees have given their approval for the content of this article.