By John Edwards, Research and Policy Officer at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre and Maria Palladino, Seconded National Expert at the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture

In this insights article, John Edwards and Maria Palladino explore the challenges faced by the European Commission in implementing smart specialisation policies with higher education institutes (HEIs). With reference to the Higher Education for Smart Specialisation (HESS) project, they present six lessons on how to create projects that align the aims of smart specialisation with those of HEIs.

Introduction

Since the concept of Smart Specialisation was conceived and applied across the European Union, there has been great interest – as well as some concern – amongst Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). This is also the case for those who have studied the role of HEIs in regional development, which now has a long tradition (Arbo and Benneworth 2006; Boucher 2003; Goddard 2016). The renewed emphasis on Research and Innovation (R&I) within the EU’s Cohesion Policy stands to benefit the higher education sector considerably, especially those HEIs located in less developed regions which receive most of the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF). However, making the activities of HEIs more relevant to regional priorities is not without its challenges. For some HEIs it may lead to difficult decisions on whether to specialise or remain comprehensive; and in the short term there is a concern that some subjects may miss out on funding because of the ‘latest policy fad from Brussels’. From a policy maker’s perspective, the difficulty is to deliver an integrated approach that addresses the different activities of HEIs, rather than treating them as separate and unconnected missions. This article explores these issues based on the results of ‘Higher Education for Smart Specialisation’ (HESS), a collaborative project of the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) and its Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture (DG EAC).

Readers of Regions e-Zine are unlikely to need a detailed explanation of smart specialisation, its academic and policy origins (Foray 2014), how it acquired a spatial logic (McCann and Ortega-Argilés 2013) and that it now underpins the EU’s Cohesion Policy. RSA Members may also know that the Association has organised two editions of the ‘Smarter Conference’ with the JRC. The second conference took place last September in Seville. However, as the Commission’s Vice President Jyrki Katainen said when launching a Communication on the future of Smart Specialisation, “it has the potential to do even more”. In fact, this approach of knowledge led, place based development is attracting interest from policy makers in many of the Commission’s services, as well as from countries across the world. With regard to higher education, the Commission has called on HEIs to contribute more to innovation in their regions, and promised to roll out the HESS project more widely (European Commission 2017). For its part, DG EAC has promoted regional engagement through University Business Cooperation (See Box 1) and support for entrepreneurial universities (See Box 2 on HEInnovate), and the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT) in particular via its Regional Innovation Scheme.

| Box 1. The University-Business Forum and Knowledge Alliances |

|---|

| Every two years DG EAC organises a University-Business Forum in Brussels: The next one will be on 16-17 May. These events showcase cooperation between HEIs and companies, especially where they have boosted innovation and helped to reduce skills mismatches. Furthermore, Thematic University-Business Fora take place in EU Member States. The last one was held in Sofia under the Bulgarian Presidency of the EU with a special focus on regional development, and the next will take place in Lisbon on 14-15 February. University-Businesses cooperation, including at regional level, is also a key objective of the Erasmus+ programme. In particular, Knowledge Alliances aim to bring together HEIs to address specific needs in the economy. There are currently 93 ongoing projects throughout the EU, many of them with a regional perspective and in some cases help to implement S3. The 2019 call is now open and the deadline for applications is in February 2019. As with all Erasmus instruments, the Knowledge Alliances are designed as EU-wide projects involving partners from several Member States, but their approach could also be replicable on a smaller (regional) scale, possibly with the support of the European Regional Development Fund. |

Higher Education and Regional Development

Drawing on academic research into the role of HEIs in regional development, three points emerge that deserve consideration from a policy perspective:

Firstly, contributing to regional development is considered to be part of the ‘third mission’ of universities; often perceived as less important than their core missions of teaching and research. This is a major shortcoming: instead of separating their regional role, universities would have a greater impact if they systematically integrated the regional dimension into their research portfolios, educational curricula and external engagement activities more broadly. Furthermore, the impact of these different missions would be greater if they were integrated, in line with the concept of the Knowledge Triangle (OECD 2016; Leten 2014).

Secondly, when considering less developed regions in particular, the contribution of HEIs to the development of human and social capabilities through education and training is likely to be greater than through the production of scientific knowledge alone (Pinto 2013). For example, investment in tertiary education is considered a key factor in the growth of the ‘Asian Tigers’ (Sen 2001). Following the smart specialisation logic, less developed regions should concentrate more on the adoption, dissemination and application of knowledge, rather than its use (McCann and Ortega-Argilés 2013). Furthermore, scientific knowledge is even more footloose than human capital and is likely to be used by knowledge intensive firms located in other places, providing little added value to the region in which it was produced. It has been shown that firms are less concerned with geographical proximity than with research quality and fit (Fitjar and Rodriguez-Pose, 2011). Therefore, an indiscriminate attempt to increase research ‘excellence’ in all HEIs is unlikely to benefit Europe’s less developed regions.

Thirdly, not all HEIs can be considered and treated in the same way. The functions, objectives and strategies of research, technical or teaching HEIs differ (Hewitt-Dundas 2012; Kitagawa 2016) and can be influenced by the regional context (Boucher 2003). Therefore, a more place-based approach to higher education is needed. As with innovation policy overall, there is a tendency to imitate successful examples that are often not appropriate in all cases (Tödtling, 2005). In relation to HEIs, a prototype is pursued based on academic spin-offs from research intensive universities, but this has only shown results in a limited number of advanced regions and universities. Teaching universities and those located in less advantaged regions would benefit from learning from other models (Benneworth et al., 2016).

These perspectives from the literature have been considered in the light of the new regional innovation strategies introduced by smart specialisation, including the entrepreneurial process of discovery, priority setting and place based policy mixes. They form the conceptual basis for the joint work of the JRC and DG EAC on the role of higher education in the design and implementation of S3.

The HESS project

Universities and other types of HEIs were identified early on by the European Commission’s S3 Platform as key actors for the design and implementation of S3 (Goddard, 2011; Kempton et al., 2013). Representatives of universities have also engaged with Smart Specialisation (European University Association, 2014) and whilst initially focusing primarily on research, overtime they have acknowledged that all their activities can have an impact on regions, especially when integrated (European University Association, 2018). When designing their Smart Specialisation Strategies (S3), regional authorities were quick to point out the presence of HEIs in their territory (e.g. at the S3 Platform peer reviews over 2012-2014), but many have never worked closely with them or understood how to engage. As the S3 process has continued, policy makers and commentators have pointed to one of the missing links in the strategies: the crucial issue of human capital (European Commission 2015), and HEIs are forefront among the institutions that can build it (Edwards et al. 2017). As a result of these observations – that regional authorities need to build stronger partnerships with HEIs that are based on a wider set of knowledge exchange activities – the HESS project was launched in March 2016.

The main activity of HESS is action research in selected European regions. While this may not fully reflect the methodological vigour of action research set out in the literature (e.g. Denscombe 2010), the principles of knowledge co-creation and impact are followed. JRC researchers and external experts work with regional authorities and HEIs to establish research questions and methods. In addition to finding out how HEIs are involved in the S3 process, an important objective is to help build closer regional partnerships. A total of five case studies have been completed in: Navarra, North East Romania, Puglia, Centre Val de Loire and Severen Tsentralen (North Central Bulgaria), and three more are ongoing: Lubelskie, Northern Netherlands and a comparison of Portuguese regions. Reports from the case studies can be found on the S3 Platform website.

| Box 2. HESS Action Research |

|---|

| The HESS action research is proving to be an interesting and novel method for policy making as well as research, as shown by some of the experiences so far: · In Navarra, the public university (UPNA) has involved its staff in territorial development challenges through the establishment of multi-disciplinary research institutes. Each one has a manager to coordinate regional engagement and internationalisation issues, and through the involvement of the university in S3 governance, researchers cooperate with the S3 clusters. Furthermore, the UPNA has linked its industrial PhD programme to the S3 priorities and developed four new undergraduate degrees related to the strategy. · In North East Romania HEIs now enjoy a closer relationship with the Regional Development Agency (RDA), thanks in part to the HESS project. A leadership workshop was organised for all the main HEIs, which was the first time that they had met each other to talk about regional development issues. The RDA has since become an intermediate authority for some of the ERDF funded knowledge transfer projects and an expert group involving academics has been set up to assess applications. · Following the Puglia case study, the Italian Ministry of Education and the National Agency for Territorial Cohesion decided to deploy the HESS methodology to integrate the ongoing monitoring and assessment of the National Operational Programme on Research and Innovation. In autumn 2018, the HESS action research approach was replicated in Sicily, Calabria, Campania, Basilicata (less developed) and Abruzzo, Molise and Sardinia (transition). Furthermore, a survey on secondary data will analyse which strategic priorities of S3 are addressed by Industrial PhDs and how they are distributed across the different regions. |

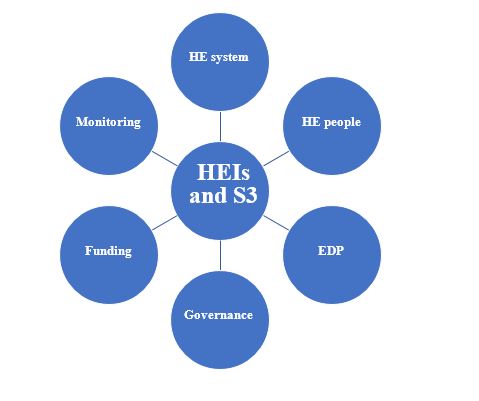

The action research has resulted in the following six areas of advice for regional authorities that wish to build partnerships with HEIs in the context of Smart Specialisation, as illustrated in Figure 1 and discussed at length in the HESS Handbook.

Figure 1. The six themes of the HESS Handbook

- Understand the higher education system: The main difficulty in creating partnerships is that the logic and drivers of classic universities come from outside the region, whether this is national regulation or peer reviewed international research networks. However, these drivers may be different in other types of HEIs such as universities of applied science. Regional authorities are encouraged to look at tertiary education in the round, and the links between different types of institutions. Whereas responsibility for regulation may be out of their hands, funding programmes can help to build a regionally based higher education system, by focusing the activities of HEIs on regional priorities.

- Build relationships with people as well as institutions: Formal processes of regional governance to develop S3 may involve HEI managers such as rectors and vice-rectors. Yet much of the regional engagement in HEIs involves individual academics, and it is important that they are brought into the S3 dialogue, for instance by participating in working groups. However, this needs to be encouraged through incentives, both financial and related to their core activities such as data collection, since most higher education systems are space neutral in terms of their performance and career appraisal systems.

- Allow HEIs to support the Entrepreneurial Discovery (EDP) Process: This is a core element of S3, and following the concept of entrepreneurial universities, HEIs can contribute to the process by drawing knowledge together and developing entrepreneurial skills among staff and students. A good first step is to use the HEInnovate self-assessment tool as described in Box.

- Closely involve HEIs in the governance of S3: Solutions to the challenges posed by spatially blind higher education systems, internal coordination within HEIs, involvement in the EDP, and the design of funding programmes, can be found through good governance structures at regional level.

- Design locally tailored funding programmes to incentivise HEIs: There is no one size fits all formula and Managing Authorities need to work with S3 managers to understand the strengths of local HEIs. Moreover, depending on how advanced the regional innovation system is, a balance needs to be struck between the development of horizontal capabilities and funding for vertical S3 priorities (although the latter can be good points of reference to structure capacity building activities).

- Make the most of technical skills in HEIs for S3 monitoring: Many regional authorities lack capabilities for S3 management, especially monitoring and evaluation. This is an area where HEIs have provided invaluable technical assistance and yet many more regions could benefit by assessing how researchers could help in data collection and analysis. This can also represent a win-win situation, in which academics can use this material for research purposes.

| Box 3. HEInnovate |

|---|

| The HEInnovate project offers an interesting opportunity to support regional innovation. It provides HEIs with a tool to self-assess their innovative and entrepreneurial capacity. It is neither a benchmarking nor a ranking tool; instead it focuses on helping HEIs to map their own strengths and weaknesses in relation to eight dimensions, and define a tailor-made improvement strategy. So far, the Commission, in cooperation with the OECD, has carried out individual country reviews based on HEInnovate in five EU Member States (Bulgaria; Hungary; Ireland; Poland; The Netherlands) while four countries are currently being reviewed (Austria, Croatia, Romania and Italy). Building on this experience, the tool is now also being used to assess the innovative and entrepreneurial capacity of HEIs at regional level, and may be used to support the upcoming revision of S3. * The eight dimensions are: Leadership and governance, organisational capacity, entrepreneurial teaching and learning, preparing and supporting entrepreneurs, digital transformation and capability, knowledge exchange and collaboration, the internationalised institution, and measuring impact. |

Conclusion and invitation to collaborate

Smart Specialisation will be reinforced in the next programming period of EU funding through the ESIF and centrally managed programmes, yet there is still much to learn and improve in the process, not least with regard to the human capabilities in regions to deliver the strategies. HEIs have a critical role to play, but there needs to be a thorough mapping of what HEIs in a particular region can offer and how this can meet demand from firms and other actors contributing to innovation. The HESS project, the UB Forum and HEInnovate will be strengthened over the coming months and the European Commission would be pleased to receive comments and suggestions from readers.

Disclaimer

Views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent an official position of the European Commission

References

Arbo, P. and P. Benneworth (2006). Understanding the Regional Contribution of Higher Education Institutions: A Literature Review.Paris, OECD

Benneworth, P., R. Pinheiro and M. Sánchez-Barrioluengo (2016). “One size does not fit all! New perspectives on the university in the social knowledge economy.” Science and public policy.

Boucher, G. (2003). “Tiers of engagement by universities in their region’s development.” Regional Studies 37(9): 887-897.

Denscombe, M. (2010). The Good Research Guide for small scale research projects. Oxford, OUP.

Edwards, J., E. Marinelli, E. Arregui Pabollet and L. Kempton (2017). Higher Education for Smart Specialisation: Towards Strategic Partnerships for Innovation.Luxembourg, European Union

European Commission (2015). Perspectives for Research and Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialisation (RIS3) in the wider context of the Europe 2020 Growth Strategy.DG Research and Innovation. Luxembourg, Publications Office of the European Union

European Commission (2017). A Renewed EU Agenda for Higher Education, COM(2017) 247 final.

European University Association (2014). The role of universities in Smart Specialisation Strategies: Report on joint EUA- REGIO/JRC Smart Specialisation Platform expert workshop. Brussels, EUA Publications.

European University Association (2018). Coherent policies for Europe beyond 2020: Maximising the effectiveness of smart secialisation strategies for regional development. Brussels.

Foray, D. (2014). “From smart specialisation to smart specialisation policy.” European Journal of Innovation Management 17(4): 492-507.

Goddard, J. and L. Kempton (2011). Connecting Universities to Regional Growth: A Practical Guide.Luxembourg, European Commission

Goddard, J., E. Hazelkorn, L. Kempton and P. Vallance (2016). The Civic University: The Policy and Leadership Challenges. Cheltenham, Edward Elgar.

Hewitt-Dundas, N. (2012). “Research intensity and knowledge transfer activity in UK universities.” Research Policy 41(2): 262–275.

Kempton, L., J. Goddard, J. Edwards, F. Barbara-Hegyi and S. Elena-Pérez (2013). Universities and Smart Specialisation.Luxembourg, Publications Office of the European Union

Kitagawa, F., M. Sánchez-Barrioluengo and E. Uyarra (2016). “Third mission as institutional strategies: Between isomorphic forces and heterogeneous pathways.” Science and public policy

Leten, B., P. Landoni and B. Van Looy (2014). “Science and graduates : How do firms benefit from the proximity of universities?” Research Policy 43: 1398-1413.

McCann, P. and R. Ortega-Argilés (2013). “Smart Specialization, Regional Growth and Applications to European Union Cohesion Policy.” Regional Studies: 1-12.

OECD (2016). Enhancing the Contributions of Higher Education and Research Institutions to Innovation; Evidence from the OECD Knowledge Triangle project case studies.

Pinto, H., M. Fernandez-Esquinas and Uyarra (2013). “Universities and knowledge-intensive business services (KIBS) as sources of knowledge for innovative firms in peripheral regions.” Regional Studies.

Sen, A. (2001). Development as Freedom. Oxford, OUP.

Tödtling, F. and M. Trippl (2005). “One size fits all?: Towards a differentiated regional innovation policy approach.” Research Policy 34(8): 1203-1219.