By Xiangming Chen, Trinity College and Fudan University, Julie Tian Miao, University of Melbourne and Xue Li, Fudan University.

Xiangming, Julie and Xue present a framework for understanding the risks involved in China’s multi-national trans-regional Belt and Road Initiative. As part of research contributing to a Regional Studies Association Policy Expo they suggest how outcomes from the worlds largest and most complex infrastructure project could be improved by taking a multi-scalar approach to risk.

:Introduction:

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a massive program of funding and construction that weaves trade and infrastructure connections across 70 countries, has the potential of reshaping globalization and ushering in a new era of South-South cooperation. However, whilst recognizing these opportunities this paper will focus on the risks relative to potential benefits of the scheme and will set out a project of research investigating risk at local, national and international scales, which forms part of a Regional Studies Association Policy Expo. The aim of this research is to develop a meaningful index measuring risk for the 70-90 BRI countries and to evaluate the factors that affect this risk index. Using data on over 200 Chinese and non-Chinese cities along or near the Belt and Road, we will explore the factors that render some cities more prepared to take part in BRI. We also plan to use three case studies of BRI projects to illustrate how opportunities and risks interact to produce varied outcomes in terms of cross-border regional cooperation. The project will also seek to communicate the implications and lessons derived from this integrated analysis to the policy community that is developing across the different sectors and spaces of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Putting the Belt and Road Initiative in Context

The fundamental policy challenge of China’s Belt and Road Initiative revolves around the complexity of its grand vision and the massive scope of the many international and inter-regional partnerships it encompasses. It reflects President Xi Jinping’s ambitious vision for China to help the world achieve “shared growth through collaboration in the common human community.” However, official rhetoric aside, the BRI amounts to a China-led globalization and a new model and round of South-South cooperation (Liu and Dunford 2016). BRI covers around 70 countries, almost all of which belong to the Global South, including the so-called transition countries in East-Central Europe, although Deng et al (2018) include as many as 93 countries. Taken together, these countries account for about half of the world’s population and 40% of its GDP. In its vast geographical coverage, the BRI encompasses six corridor-shaped, boundary-spanning regions and 274 cities with populations of one million or more, 105 of which are located inside China (Li and Tu 2018). This diversity of countries and cities presents a challenge to policymakers and other stakeholders, such as funders and construction firms in understanding the complex economic, political and spatial distribution of risks and in realizing opportunities that can be mutually beneficial. The balance between the BRI’s promise vs. its territory-specific risks and blind spots is the crux of the policy problem and the focus of this Policy Expo.

This policy challenge looms even larger given the massive price tag for BRI, which is estimated to increase from US$1.4 trillion, to as high as US$8 trillion through 2030. As the driver of BRI, China will provide the bulk of this financing through concessional loans and other forms of investment. Given China’s intermediate position in global value chains, one aim of the BRI is to link up less developed countries and regions along the Belt and Road, which are primarily exporters of primary and intermediate goods and importers of higher value-added products. International development agencies such as the United Nations Development Programme and African Development Bank therefore see the BRI as facilitating accelerated industrialization in countries that are willing to join and work with China.

Nevertheless, the BRI carries certain, often unrecognized, risks that raise the policy stakes. In response, government agencies, international organizations and think tanks working inside China and internationally have produced a number of reports focused partly on risks, such as debt service and sustainability. However, the lack of rigorous academic studies means we know little about the full extent of these risks and the factors that produce and sustain them across spatial scales and boundaries. The small body of published research including recent work by Chen has focused on the BRI in limited regional contexts (e.g. Callahan 2016; Chen 2017; Chen 2018a). While national policymakers in China and other BRI countries may face risks in debt service and political instability for large-scale and expensive infrastructure projects, the latter are generally sited within and stitched together across key cities and regions serving as hubs or cross-roads for the BRI. As capital investors or project hosts, these diverse subnational units also confront risks associated with the construction and sustainability of BRI projects given their varied locations, development trajectories, physical connectivity and governance capacity. The relative power and resources of national vs. subnational governments of BRI countries is therefore a potential key point of financial and operational risk. Defining and predicting these risks can lead to proactive and remedial policies that are capable of delivering shared development benefits.

State, City, Project, Region, Rethinking the Belt and Road Initiative

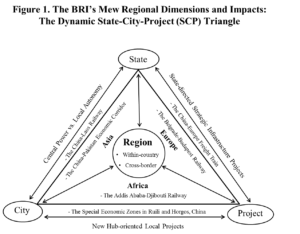

Assessing BRI’s risks should not be approached in a narrow and technical way, as it has been previously. Instead, research should be guided by a broader framework that takes into account the balance between the operational risks and development opportunities. In addition, this framework should address how the risk-opportunity balance is embedded into the multiple levels and units of observation and analysis involved in the BRI. Why? Because, the massive scope and myriad actors of the BRI could rescale its risks vs. opportunities into the clear and related domains of the state, the city, and the project that produce new regional trends and impacts (see Figure.1).

In Figure 1, we conceptualize BRI by distinguishing and reconnecting these three important spaces, (state, city and project), which should be investigated individually and in relation to each other. This framework moves beyond the prevailing focus on the nation-state in the discourse about BRI by scaling down to the city (where), and the project (what). These two spaces, relative to the state, are the where and what that localize and concretize BRI’s risks and opportunities, even though the national state often shapes and redistributes them from above. By triangulating them, we identify and connect each of these dyads as both a discrete and relational focus of analysis.

In a discrete sense, the state is where we begin our inquiry into BRI’s risks and opportunities. While the most common count of the countries covered by BRI is around 70, Deng et al (2018) posit a more inclusive number of 93 across Asia, Africa, and Europe. This relatively large number allows us to cover the maximum scope of BRI through a cross-national quantitative analysis of indicators that pertain to the balance of risk and opportunity associated with these countries as existing or potential participants in BRI. By including the city as a unit of analysis, we capture the important middle level of cities, and their regions, that can reveal where potential risk and opportunities can occur as BRI “touches down”. If we follow the 93-country scope of BRI, there are 252 cities with one million or more people in these countries (Deng et al, 2018), representing a rather comprehensive geographical scope of city-level analysis. Given the limited data for many of these cities, we will pursue the city-level analysis using the fullest subset of these 252 cities for which we can find indicators for comparable, quantitative analysis. As the third leg of the triangle, the project is the most basic component of BRI and ultimately matters the most to its success. Numerous in number and spread unevenly across a large number of cities and countries, the projects of BRI carry the collective concentration and spread of risk and opportunities. In light of the very large number of projects and the lack of information, we aim to combine a limited statistical analysis of the available data on the largest possible number of BRI-related projects with a few in-depth case studies of strategically important projects, such as those identified in Figure.1.

In the dyadic terms of our triangular framework, we suggest that the relative power of the central state to local government is the key factor in balancing the risk and opportunity of BRI within and across countries. While the Chinese state drives much of the financing for BRI projects, the latter must be sited in and through both Chinese and non-Chinese cities that are often the intended local beneficiaries and are expected to generate more development opportunities. If these cities are relatively autonomous as in the case of capitals and/or economic centers, they tend to benefit more from potential opportunities from BRI projects while bearing little risk. Small and weak cities with less autonomy relative to the nation-state, in contrast, tend to be more vulnerable to the risk side of BRI projects, especially if and when they fail to materialize. The nation-state can certainly bypass the city to initiate strategic BRI projects that are capable of creating significant long-term cooperation. For example, the China-Europe Freight Trains provide many overland and cross-border transport links that enable a greater volume of and more efficient trade through Eurasia (Figure 1). While some of these train routes run through key logistic hubs, they are more important for inter-state cooperation through trade. Finally, the city reappears as the anchor for some crucial BRI infrastructure projects such as special economic zones that in turn can facilitate trade through assembly or full manufacturing. These city-project connections generate and sustain the rise and continued importance of new hub cities for BRI.

By employing this framework we aim to understand and produce new policy responses to the opportunities and risks posed by the BRI. In particular, we believe this approach is well placed to address the following four questions, which are of great importance to the success of the BRI:

- What are the perceivable challenges to BRI from many participating players across the global, national, regional and local levels and boundaries?

- How can we define and differentiate BRI’s opportunities vs. risks?

- How do we measure and predict the risks embedded in and externally associated with BRI?

- How can a systematic risk assessment lead to effective bilateral and multilateral policies for achieving the BRI’s desired outcome of inclusive and sustainable development?

Methodology

To facilitate policymaking in a wide range of contexts, we have developed a framework to guide this integrated study to identify the main risks for BRI and reveal their causal or contributing factors. We plan to do so by: 1) constructing a composite Risk Index, or a series of similar individual indices for BRI countries, cities, and projects; 2) modelling the factors assumed to affect these risks relative to opportunities; and 3) examining the relationship between risks and opportunities involved in selected major infrastructure projects along three BRI corridors as case studies.

Unlike the small, existing number of reports on BRI (eg. The Economist Intelligence Unit, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Center for Global Development, Cushman & Wakefield, among others), which focus exclusively on the national and inter-state scales, this approach will generate policy proposals based on a two-tiered study at the national and subnational levels. Further, our study also aims to not only clarify the nature and sources of risks for the BRI countries, but also to reveal the broader geographical spread of risks embedded in cities and regions spanning national boundaries. To do this we will conduct a cross-national analysis of risk factors for 70-90 BRI countries, which will be accompanied by a quantitative analysis of two sets, non-Chinese and Chinese cities, in an attempt to compare how BRI-related risks differ between Chinese cities and non-Chinese cities. Both analyses will keep the intended and potential opportunities for BRI’s development benefits as the reference target. The total numbers of cities in either set will be determined by the availability and consistency of data. This approach will allow us to break down the risk-opportunity nexus for BRI countries to the local level, and construct a reference framework for follow-on subnational policy scrutiny. The third prong of our analysis will focus on selected infrastructure projects for three BRI corridors that span national and regional boundaries. Here our focus will be contextualising our quantitative analyses in representative nation-city-project triangles. By combining the three analytical approaches suggested by our conceptual framework, we aim to lay the groundwork for advancing complementary policies that can mitigate or even forestall different risks and improve the chances for success in BRI projects.

National-level indicators will be mainly compiled from the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, United Nations databases, as well as Eurostat and European Data Portal. We will explore the possibility of adapting Moody’s sovereign credit risk ratings vs. constructing a new index and/or indexes that can measure multiple dimensions of the BRI’s risks. This index can be modelled as a dependent variable in response to national economic, political and social indicators. While our pre-project data mining reveals that available data for the main cities in BRI countries minus China may be uneven, we will gather as many annual indicators as possible from international and country-specific statistical sources. Regarding quantitative data on the Chinese cities located along or near the China portions of BRI, we plan to compile available indicators from municipal yearbooks. This will allow us to build an index that reflects the extent to which the approximately 100 Chinese cities, with one-million-plus populations, can participate in BRI relatively risk-free. For data on particular BRI projects, we will rely on China Global Investment Tracker, which is compiled by the American Enterprise Institute and The Heritage Foundation. We aim to include approximately 100 non-Chinese cities for a parallel statistical analysis derived from Deng et al (2018). Regarding independent variables with presumed effects on this index, we will include economic indicators such as GDP, GDP per capita, growth rate, industrial structure, foreign trade, capital flows and distance to the closest major city, relevant social indicators include membership of international organizations, population size, level of urbanization, social welfare spending, unemployment rate and so forth. Our case studies will target the China-Southeast Asia borderland, the New Eurasian Land Bridge and the China-Central Asia-West Asia Corridor, based on their geo-economic significance and extended regional implications.

Early Findings, Policy Directions

To illustrate the utility of our approach, we highlight early evidence from two of our case studies. The China-Laos Railway and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), two of the most important BRI projects (see Figure.1). The China-Laos Railway costs more than half of Laos’ GDP and depends on China for the bulk of its financing. It therefore subjects Laos to a potential and likely long-term risk of a heavy debt burden. This risk is heightened if the projected economic benefits from millions of Chinese passengers including tourists to Southeast Asia through Laos fail to materialize (Chen, 2018a, 2018b). A similar debt risk looms for Pakistan from the CPEC that will cost over $60 billion, the bulk of which comes from the Chinese government financing (Chen, Shahzad and Tariq, 2018). Compounding economic risks include the feasibility, uncertainty and coordinated development of multiple large-scale projects in energy, transportation, and manufacturing through special economic zones in Pakistan. This appears to have already occurred, as some contracted companies building parts of the CPEC projects have been reported to be falling behind on paying wages. Planned to run through Baluchistan Province, the CPEC is also exposed to political and security risks from the ongoing conflicts associated with a local independence movement. Returning to the national level, Laos and Pakistan are two of the eight most risky countries involved in the BRI. This preliminary evidence lends initial confirmation for studying BRI through the proposed triangular framework.

By constructing a meaningful Risk Index and uncovering the main sources of risk involved in the BRI, we will develop practical insights that benefit three different groups of policymakers and stakeholders. First, we aim to inform both the countries already committed to BRI and those who are ambivalent about it or opposed to it, such as the US, Japan and India. We believe the shortage of a systematic study of the risks vs. opportunities has created and sustained a lack of confidence and a level of suspicion. An aim of this Policy Expo will therefore be to bring the much-needed evidence to BRI countries to act more confidently, while providing evidence that will also allow countries that are either suspicious of, or against BRI to adjust their policies accordingly.

Second, for Chinese national and local policymakers, such as the The Export-Import Bank of China, our research will create a body of evidence that shows while China is well intentioned to implement BRI as a global public good, it can do so better by understanding and managing the varied risks that may threaten and even derail some beneficial projects. If the small number of BRI countries, especially Pakistan and Laos carry high risks in terms of the debt/GDP ratio (according to a recent Center for Global Development report), it should alert Chinese policymakers to rebalance the priorities of bilateral political relations vs. practical economic concerns. In light of our evidence on the risk for any Chinese cities to participate in BRI, municipal and business leaders can be more judicious in decision-making based on a systematic assessment of their desires to follow the national policy of BRI in light of local capacities.

Third, while international development agencies such as the United Nations, the World Bank and the regional Development Banks of Asia and Africa are interested in collaborating with the BRI to promote shared development goals, they can also use the evidence provided by this policy expo to better align and cooperate with China and BRI countries in jointly financing projects with the least risk and the greatest potential for shared benefits. The beneficiaries of this research may also include the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and China’s Silk Road Fund, as they can undertake and contribute to more targeted and effective financing with better knowledge of the relative risk and opportunities facing diverse national, regional and local actors in BRI.

Given the variety of the groups targeted by our Policy Expo, we will adopt an integrated and engaged strategy to leverage policy impact. Specifically, we will rely on the MAPS approach (Mainstreaming, Acceleration and Policy Support), which was adopted by the United Nations in implementing its 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. To achieve Mainstreaming, our Policy Expo will explore possibilities of tapping into the broadcasting channels of two influential platforms. The first is the UN Development Group with which we intend to share our findings through its 2030 Agenda blogs; and the other is China’s One Belt One Road 100 Forum, the official talent pool for debating and advising on BRI. Since Acceleration targets priority areas, trade-offs, bottlenecks and partnerships, we will offer policy-relevant evidence at the regional and city level that goes beyond the conventional focus and practice at the national and international level. This policy outreach could be achieved through adopting different publishing channels including multimedia such as 1-2 e-newsletters and blogs published by our host institutions . The academic community studying the BRI will also be informed through traditional journal publications, one of which we will seek to publish open access in Regional Studies, Regional Science. A policy-oriented book in the RSA Impact and Policy Series will also be produced aiming to synthesise the results of this study. In delivering Policy Support, which employs research skills and expertise, we will use this Policy Expo and its results as a longer-term databank and set of resources that can be updated by our continued research to inform policymakers and stakeholders about BRI. The fact that we as researchers on this project based in, Europe, the US and China, can collaborate on this project gives our research another distinct advantage in leveraging interest from a variety of international stakeholders. Having already established several connections and potential partnerships with BRI research outfits in China including the new BRI Research Institute at Fudan University, Hong Kong University and beyond, we are very well positioned to secure extended research and policy impacts. Larger scale research collaborations with stakeholders will also be sought for throughout the course of the project and after to develop this body of knowledge on the BRI.

Conclusion

China’s ambitious Belt & Road initiative, combining the overland ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ and the ‘21st-Century Maritime Silk Road’, emphasises the coordination of development policies, financial cooporation, strengthening investment and trade relations, forging infrastructure networks and deepening social and culture exchanges. Its sheer scale in geographical coverage and complexity in formats and partners involved call for detailed risk-benefit analysis that to date has been missing from both academic and political spheres. To many observers, this initiative represents China’s effort to challenge and reconfigure the existing global political and economic status quo, a challenge which could bring new growth opportunities to other developing countries and cities involved in the numerous projects. On the other hand, we see the potential financial and even political risks to the cities and nations engaged, which could potentially be damaging to the project if left undiscussed. A clearer picture on the level, composition and nature of BRI risks to participating countries and cities is therefore a necessity if the BRI is going to achieve its ambitious goals.

In this article, we have outlined the rationale, framework, data sources and the dissemination strategies that our research relies on. We look forward to presenting in more detail the data analyses and case studies that we will undertake as part of this project and we welcome readers of Regions E-Zine to contact us and be part of an emerging group of scholars working on the Belt and Road Initiative.

References

Chen, Xiangming. 2018a. “Globalization Redux: Can China’s Inside-Out Strategy Catalyse Economic Development Across Its Asian Borderlands and Beyond.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11 (1): 35-58;3.

Chen, Xiangming. 2018b. “Rethinking Cross-Border Regional Cooperation: A Comparison of the China-Myanmar and China-Laos Borderlands.” Pp. 81-105 in Region-Making and Cross-Border Cooperation: New Evidence from Four Continents, edited by Elisabetta Nadalutti and Otto Kallscheuer. London: Routledge.

Chen, Xiangming, S. K. Joseph, and Hamna Tariq. 2018. “Betting Big on CPEC.” The European Financial Review (February/March): 61-70.

Deng, Zhituan, Yubo Liu, Qiyu Tu, and Chuankai Yang. 2018. “The Silk Road’s Nodal Cities: Recognizing and Leveraging the Pivots of ‘BRI’s Construction.” Pp. 1-50 in The Blue Book of World Cities, No. 7. Shanghai: Social Science Academic Press. (in Chinese.)

Li, Jian and Tu, Qiyu. 2018. “The Silk Road Cities Corridor.” International Urban Observation. March 2; online.

Liu, Weidong and Dunford, Michael. 2016. “Inclusive Globalization: Unpacking China’s Belt and Road Initiative.” Area Development and Policy 1: 323–340.