By Lisa De Propris, Professor of Regional Economic Development, Birmingham Business School.

Applying for research funding is now firmly part of contemporary academic life. One is asked about it when applying for jobs, when attempting to be promoted and it is part of many performance metrics at the department, school or other aggregate level. In social sciences this is quite a recent phenomenon and has acquired different levels of importance across European academia. In this short piece I will share my experience about why I have applied for research funding, what funding I have won, what difference it has made to my career, and most importantly what I have learnt on the way.

My experience in bidding for and managing grants started in 2002 and I have since been involved in or led research grants almost every year, most of which have been EU funded grants. Somewhat unsurprisingly, besides this list of successful grants, there is an equally long list of non-successful bids, which of course took up an equally huge amount of time. And this is the first point worth making. Writing a bid is demanding, challenging and takes up time.

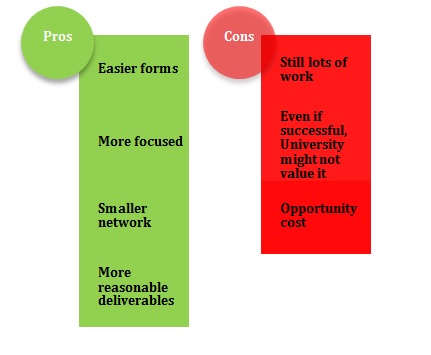

The experience of applying for funding can vary. Being part of a bid nevertheless requires ideas, commitment, expertise, contacts, and above all time. One can apply individually, lead a small team of colleagues, be part of a large national or international network or consortium, be a co-investigator, or play the leading role as a principal investigator of a large national or international network or consortium. These options each require different demands and different expectations. In my experience they were the steps on a learning ladder. I started with small bids and gained experience of managing small grants before engaging in bigger and more complex international grants such as FP5, FP7 and now H2020.

The advantage of this has been to allow my research agenda to lead my research funding, rather than the other way round. There are situations where early career researchers can be part of well set up research organisations and are from the very beginning engaged in large grants, learning quickly both about bid writing and grant managing. So moving from small to big grants as I have done might not be for everybody, or relevant to everybody’s experience.

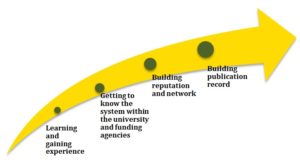

What I have learnt over the course of the many large grants I have been involved in has been valuable for my career and my profile. Within the University, I have gained the ability to connect and link different resources such as finance, legal advice, research support, and human resources. These resources are often located at the University level and this has meant I have had to learn to reach out beyond the confines of the department and school.

At the same time, every bid has also meant creating a team of colleagues within the department or school to deliver the research content of the grant. Even small projects are likely to require a pool of competences. Good team work is crucial to glue a group of researchers around a theme with sufficient commitment to take the project forward and deliver the agreed research output. As a result, I have had to develop my project management skills along the way.

Involvement in successful grants has in my case been recognised in my workload, which has allowed me to manage and balance my commitments across the many demands of academic life. Last but not least, academics are increasingly expected to apply for grants and be successful, in what sometimes appears to be more of a box-ticking exercise than anything else. However, in my experience writing grants has had other spillover benefits. It is often argued that good networks help successful bids, and this works the other way round too. The experience of writing bids and of being part of successful grants have been critical in enabling me to build an international profile, to engage actively in international communities of scholars in my area, together with sharing and comparing research hypotheses and findings. Large grants as such, provide the funding and the opportunity to scale up one’s research by adding a national or international comparison.

Being part of and leading large grants made a great difference to my career on a number of levels: networking, publications and exposure. Being involved in grants that fit my research agenda enabled me to work with colleagues with complementary expertise, attuned interests and an international perspective. My networks have thickened over time with collaborations and exchanges that have grown. Joint research has emerged and with it joint publications, contributions to edited volumes, special issues and top ranked publications. These collaborations and publications have given exposure to my work and raised my profile.

From a research leadership point of view, at every bid, I have learnt how to read the requirements of bids and the vocabulary that goes with them, such as aims, objectives, methodologies, work packages, networks, deliverables, impact, dissemination and so on. I have developed an understanding of the importance of bringing together a well balanced team of colleagues with different, complementary but connected competences. The same attention has to be paid when putting together a team of colleagues within a project or a full scale international consortium. In parallel with contributing to the scientific content of the bid, there are also crucial tasks such as preparing the budget, thinking about resources, and considering ethical and legal implications. Finally, from being part of bids led by more experienced colleagues, I saw how my contribution was expected to fit in and how a full proposal is knitted together. As one can see, an enormous amount of time and effort is invested in each bid.

When successful, a bid comes to life and a research project has to emerge that delivers what has been promised. Amidst the enthusiasm for the award comes the anxiety of having to roll out all the activities designed and scheduled, as well as hiring staff, signing contracts and negotiating workload weightings. The implementation of the project requires in almost all cases, scientific and financial reporting. I therefore learnt to draw on the expertise of ‘post-award support’ teams in the university for dedicated advice and contribution.

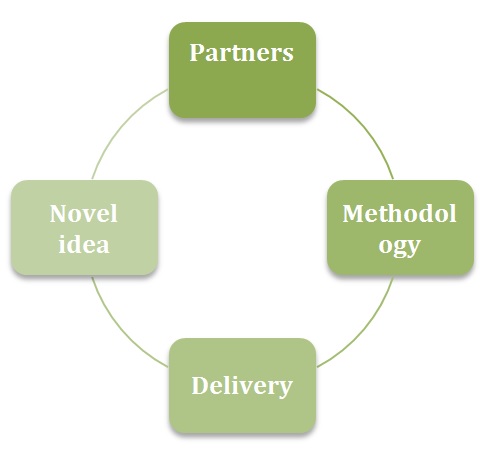

It might seem common sense but to me a good bid requires four elements: a truly novel idea, a robust and appropriate methodology, a competent consortium and reliable implementation.

A couple of points are worth noting here: To access large grants, for instance EU funding, one has to have a truly novel idea. This is however not enough: there must be a strong fit with the call. Trying to fit even a very new idea into a call that is on something else can be a recipe for disappointment. Looking for the right call to carry an idea forward is crucial.

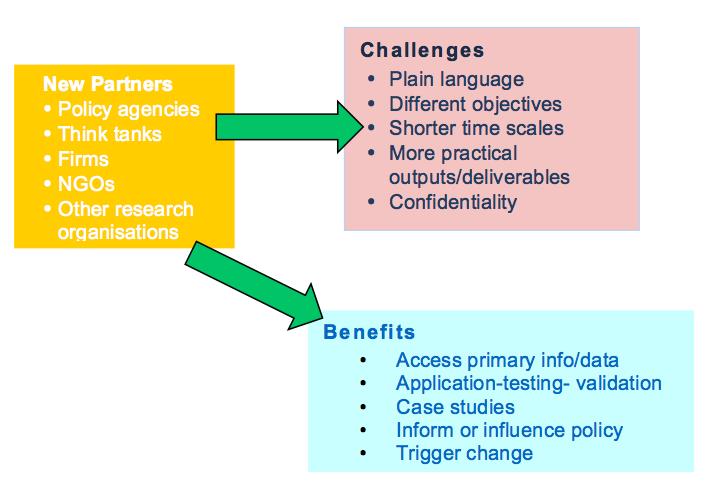

The composition of the consortium is increasingly challenging: firms, think tanks, NGOs, policy makers or not-for-profit organisations are required to be included to allow research to dovetail with economic and social interests. This makes research relevant, engaged and impactful; but it also pushes academia to forge linkages with new partners who have very different expectations, time horizons, time commitments and view points.

Recent statistics show that the chance of being successful when applying for EU funding is low: in 2016, the overall success rate of eligible full proposals under the first 100 H2020 calls was around 14% (vs 20% for FP7 calls). Around 38% of successful applicants were newcomers, in particular firms, against only 13% in 2013, the last year of FP7 (click here).

There are still gender imbalances especially when considering principal investigators. However, for the social sciences, there are simple measures that might address these imbalances. For example, there are still funding agencies that award grants to all-male consortia, but these practices are starting to be scrutinised more.

Brexit will change UK academia’s access to EU funding the UK has been a net recipient of EU funding. Routes to funding are likely to change, likely becoming more challenging in the case of a so-called hard Brexit. This will divert British universities to apply to other funding agencies such as UKRO, the British Academy or the Leverhulme Trust. Across the EU, this will mean that UK academic institutions might be unable to participate in EU bids in any capacity, forcing a re-composition of networks and contacts and more fundamentally a re-evaluation of a changed geography of competences without the UK.

As a conclusion remark I would say that applying for large grants has mattered to me and had a big impact on my career. Although there are clear benefits, writing bids is demanding and winning is uncertain. Some would argue that there is a trade off between writing bids and writing papers, but this is in my view a false trade-off. Evidence based research requires more and more stakeholder engagement. Research needs to be impactful and again this demands mechanisms to involve non-academic actors from the start of the grant. Ultimately, grant capture has become part of how we carry out our research.