Writing your first academic article

By Marcin Dąbrowski, Department of Urbanism, Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment, Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands.

As academics, we must debate our research with peers, build on the existing body of research to address knowledge gaps and contribute to developing knowledge and theories that help us make sense of the increasingly complex and uncertain processes that shape regional and urban futures. We are also increasingly expected to step out of the ‘ivory tower’, engage with traditional and social media, co-create knowledge with stakeholders in the ‘real world’, and participate in a dialogue with society at large. Consequently, we witness the emergence of new (often online) tools and platforms to debate and spread knowledge and engage in these interactions. Despite all this, peer-reviewed research papers published in authoritative scholarly journals remain the cornerstone of academic work and the main medium for scholars to spread insights and lessons from their work.

However, the bar for publishing in highly-ranked academic journals is very high. Moreover, academic writing can be frustrating and very daunting, not only for beginning researchers. There is good news, though: writing academic papers is a craft, and like any craft, it builds on a set of principles, skills, and formulas. All of these can be learned and developed. In this short article, I outline some of those, along with ideas and tips on how to begin and succeed in writing your first academic paper.

How to start?

Most of us have experienced ‘blank page syndrome’, being petrified by the prospect of starting to write a research article and not knowing where to begin. While there is no ‘silver bullet’ solution for this, it may be a good idea first to determine your paper’s purpose and ‘sales pitch’, which should underscore the urgency of the problem you address and the relevance of your research in addressing it. Who am I writing for, and what makes my research relevant and engaging for that audience? Does my research solve a puzzle or address a challenge others have also grappled with? Then, in the second step, the questions to ask yourself would concern the existing studies and bodies of theory that the paper builds on and the knowledge gaps that could help bridge. Answering those questions will allow you to create a ‘narrative hook’ to grab your readers’ attention (you should do it from the very first lines of your paper) and position your work against that of others.

Then, the third step is to ask yourself what is new and original in your research? It is worth noting here that scientific research is about adding a small ‘brick’ to the larger ‘edifice’ of knowledge. This means that you do not have to develop a grand new theory explaining the phenomenon you study or propose groundbreaking new methods. To be original and bring new insights, it may be enough to propose a new take on an existing theory, nuancing it or challenging its applicability in a specific context. It may also be about proposing and testing a new combination of research methods, bringing new original empirical material from your case study area, or shedding light on a new problem that others have yet to point out.

The fourth question to consider is: who am I writing for, and what will be the key message I want to convey to that audience? In formulating this key message, conciseness and a focus on a clearly delimited issue (perhaps only a distinctive part of your research) are critical, as we often tend to cram too many aspects of the research into one paper, which will make it difficult to fit within the word limits that the journal sets and to deliver a clear and coherent argument in the paper. By answering these questions, not only will you have written up the bulk of your paper’s introduction, but you will also have gained confidence and drive to write up the paper.

Beyond this, the beginning of the paper write-up process should start with a clear plan. First, it is essential to schedule writing time and set milestones towards completion, being realistic about the time that this will actually require (many of us tend to be over-optimistic about this, especially when English is not our native language). Second, it is equally important to determine early on the structure of your paper, its main parts with the main messages and a target length in the number of words, and – if you are writing together with colleagues or supervisors – divide labour in writing up these parts between the co-authors. But how to actually do this, you may ask. More on that in the next section.

Is there a formula?

There is no one single way of writing an academic paper. Journals publish different types of papers, from research papers with original empirical content through literature reviews, policy discussion papers, and commentaries to conceptual pieces. The most typical is the first one. Even for this type of papers, there is no particular formula to follow, but there are some rules, conventions, and must-have elements within the structure of the paper.

While you may arrange the sections of a research paper differently, the conventional approach is as follows. First, you should set the study in context, explain how it fits within the ‘bigger picture’, the research’s relevance, and how it adds to previous scholarship. Second, you bring in the content, the heart of your paper, which includes your findings and an explanation of your methodology. Third, you close with conclusions and discussions on the main takeaways.

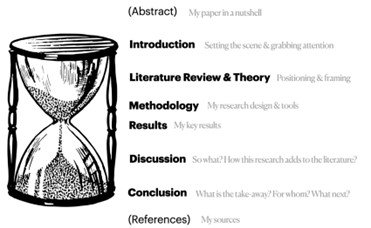

Figure 1. Three pillars of an academic article and the red line to follow.

Typically, these elements are spread across five or six paper sections of 6,000-8,000 words. These sections include: 1) introduction, 2) theoretical background or literature review, 3) methodology outline, 4) results of the research, 5) discussion, 6) and conclusion (the latter two are sometimes merged). On top of that, there is also the abstract, which is your paper in a ‘bite-size’ format, giving a quick impression of what your article is about, how you did the research, for whom it is relevant, and why one should read it. Naturally, there is the references list at the end, all your sources, prepared in the referencing style the journal uses.

A good metaphor to summarise this structure is that of an hourglass. The first sections – introduction and literature review or theoretical framework – are meant to be broad. The introduction should place your research in the wider context and explain the relevance of your work in addressing the burning urban and regional challenges. Then, you narrow down the focus to position your research against the existing literature and frame it with the most relevant concepts from that body of work. Then, at the core of your paper, you narrow the focus further to describe the specific methodology used in your research and present the primary empirical material and findings. After this, in the discussion, you should open up again to explain how your findings relate to those from the previous research done by other scholars and highlight what you add to the literature you reviewed earlier. Finally, in the concluding section, you should reiterate your main findings, answer the research question, and point out the implications for practice and avenues for further research.

Figure 2 The main parts of a typical academic paper (Source).

Remember, though, that this is merely a convention that helps the reviewers and readers navigate your paper and helps you convey your findings and ideas. Like any rules, they can be bent and broken, opening up new perspectives and adding a bit of your own creative flair.

How to succeed?

We have now covered the basics of starting up the writing process and structuring your academic paper. This is, however, only the beginning of the writing process, which entails a steep learning curve. Here is a set of tips that could help you in writing:

- First impressions matter: To make a strong initial impact on your readers, make sure to develop a catchy yet informative title and abstract with carefully selected keywords that best reflect the content of your paper. These elements are crucial in capturing readers’ attention and enticing them to keep reading your paper.

- Less is more: A PhD or another research project typically has several components and tackles several research questions. This is usually too much to cover in one paper. Thus, make sure to select a coherent ‘chunk’ of your project that can be effectively communicated within the word limit given by the journal in which you want to publish. Also, focus on the essential aspects of the research, the most important and relevant insights, to maintain focus and clarity.

- Be strategic: Choose a journal to which you submit your work strategically. For this,do consider where the authors you cite most publish their work or where your research design will be deemed more innovative. Then, having made the choice of a journal, tailor your paper to grab the attention of its editors and try to engage in the debate within the papers published earlier in this journal. You can also flag this up in the cover letter supporting your submission.

- Embrace criticism: Rejection is a common experience in academic publishing. It happens to all of us, including ‘high-flying’ senior scholars. Rather than being discouraged by a rejection or request for major revisions, view this criticism as an opportunity to improve your writing and advice to deliver a better paper. What doesn’t kill you… makes you a better writer.

- Cut the jargon: Write plainly, aiming for conciseness and clarity in your language. This means avoiding excessive jargon or technical terms that may alienate your readers. There is a temptation in academic writing to ‘hide’ behind wordiness and complex terms, but this only makes reading such work difficult and frustrating. Instead, we should strive to communicate our ideas in a straightforward and accessible manner to make the biggest impact. By keeping your writing clear and jargon-free, you will also make the editors and reviewers happier.

- Don’t force reviewers to search for your arguments: Reviewers are extremely busy people doing peer-reviews for free. Make sure your key points and arguments are clearly highlighted and easily identifiable. By presenting your ideas well-structured and organised, and flagging up the key takeaways, you make it easier for reviewers to engage with your work. Conversely, if your core arguments are buried under an avalanche of words and digressions, the reviewers will likely be less positive about your paper.

- Follow the conventions: Adhere to the established writing conventions and guidelines, particularly in referencing and formatting. Make sure to familiarise yourself with the specific instructions for authors provided by the journal you are submitting to. It sounds obvious, but you would be surprised to see how often this needs to be addressed.

- Focus on conveying useful knowledge: Highlight valuable insights and knowledge that are useful to your peers and target audience. Consider the practical implications of your work, its relevance for policy and real-world practice, while also stressing its usefulness for future research. That way you can deliver a more impactful paper.

- You can disagree with reviewers: This tip may come as a surprise to beginning academics, but it is fine and quite common, in fact, to object to (some of) the feedback one receives in the peer-review process. If you receive critical remarks from reviewers, it is absolutely acceptable to disagree respectfully, providing reasons for this. If you think the reviewer misses the point, clearly explain your reasoning when responding to the comments comprehensively and thoughtfully. The editor may be on your side, too.

- Aim high because you can do it: If your research is original, brings something new and interesting to the debate on your topic, and is based on a sound theoretical and methodological foundation, there is no reason to aim for lower-ranked journals. If your research is sound and the paper is written following the above advice, do not hesitate to submit your paper to a prestigious journal. After all, the worst thing that can happen is that your paper gets rejected, and you receive feedback from experienced scholars, which will help you improve it.

And to round off this long list of tips, an extra piece of advice: You are not alone. Academics are part of a community, and publishing itself is a community endeavour involving volunteer work from peer reviewers and editors. You can ask your colleagues, mentors, and co-authors for feedback on your work and suggestions on communicating your research in a high-quality academic paper. Collaboration and peer support can greatly enhance your work’s quality and impact.