By Alex de Ruyter, David Hearne and Vangelis Tsiligiris, Centre for Brexit Studies, Birmingham City University, UK.

Drawing on findings from an international survey of RSA member’s attitudes towards Brexit, this insights articles explores what RSA members consider to be the likely impacts of Brexit on the economy and higher education sectors of the UK and EU.

Background

Brexit continues to dominate the political landscape of the UK, as negotiations for a Withdrawal Agreement with the EU reach their climax and the torturous process of having this ratified by both sides takes effect. Notwithstanding the prospect of a no deal, the expectation is that a transition period can be secured to ease adjustment, whilst the parameters of a new economic relationship begin to be negotiated upon. Within this context, an overlooked area of concern has been the potential impact of Brexit on the higher education sector in the UK (and the rest of the EU).

Indeed, the HE sector in the UK currently has strong links to the EU through funding via Horizon 2020, the Erasmus student exchange scheme and the vital contribution that EU staff make to UK universities, with 17% of academic and 6% of support staff being from other EU countries (Universities UK, 2018). As such, Universities UK (2017) called for negotiations to ensure continued access to the EU’s FP9 innovation and research funding programme and Erasmus+ mobility scheme, as well as an immigration system with “minimal barriers” to enable EU academics and students to continue to study and work in the UK.

It is not surprising, therefore, to find that a majority of business schools in the UK are anticipating a fall in the number of EU students (CABS, 2018). Nor is it surprising, in light of the fact that some 15% are already experiencing a fall in EU funding, that they are looking for ways to mitigate this. Replacing European academics, however, may be an even more difficult challenge.

Amidst this backdrop, the Centre for Brexit Studies at Birmingham City University was recently commissioned by the Regional Studies Association to create and analyse a survey of the views of its membership on Brexit. The survey involved a mixture of quantitative and qualitative responses on issues where the membership might be expected to have an unusual level of expertise relative to the population at large. As such, the survey sought to ascertain members’ views on several key aspects of Brexit, specifically:

- What are the overall views of the membership with regard to Brexit?

- What do they feel the economic impact of Brexit will be on both parties in the short and longer term?

- Will Brexit exacerbate existing regional disparities and spatial inequalities and, if so, what might be done to alleviate these?

- What do they feel the impact of Brexit on higher education and regional policy and practice is likely to be?

- What effects (if any) might Brexit have on members’ careers and personal lives?

Although a majority of learned societies take a view on Brexit – see, for example, this contribution from the British Academy (2017), only a minority appear to have actively canvassed their membership and most of these have taken a slightly different approach to the Regional Studies Association. The British Psychological Society, for example, sought the views of its membership but has taken a qualitative approach with a small number of relatively detailed views expressed (The British Psychological Society, 2018).

The Society of Spanish Researchers in the UK (with a membership of around 600, most of whom are either PhD students or early career researchers) sought the views of its members, focusing specifically on the personal impact of Brexit (Society of Spanish Researchers in the UK, 2018). Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Society found that almost half believe that Brexit will have a major impact on their personal and professional lives and 45.2% of them are waiting for the outcome of negotiations before deciding on future plans and a quarter have already changed their plans as a result of Brexit (ibid.) Particular concerns were the threat of additional bureaucracy to live and work in the UK, and the economic impact.

On a larger scale, the Institute for Employment Studies, surveyed EU nationals working in the higher education sector in the UK on behalf of the Department for Education. The survey has been roundly criticised due to its choice of language, asking respondents whether they were “considering a move back home” (Grove, 2018). In light of this comparative paucity of data on the views of academics in the field, we are now in a position to present some initial findings.

Survey findings

The survey contained a total of 165 valid responses, although not all respondents answered every question. Of the total, 27 of the respondents indicated that their nationality was British, 93 were from elsewhere within the EU and a further 45 from outside of the EU. This matches the demographics of the RSA membership, which is concentrated in Europe, albeit with members around the world.

Our data on respondents’ locations indicates that a significant number of European members reside in the UK (around 20%), whilst a smaller proportion of British members (circa 10%) reside elsewhere in the EU. In total, some 48 respondents were located in the UK, 73 in the rest of the EU and 44 elsewhere around the globe. In terms of ages, around a quarter of all respondents were under 35 and half the total respondents were under 41. British respondents skew slightly older than this, with a median age of 50. There were no significant differences in the age profile of EU and non-EU academics (excluding the UK).

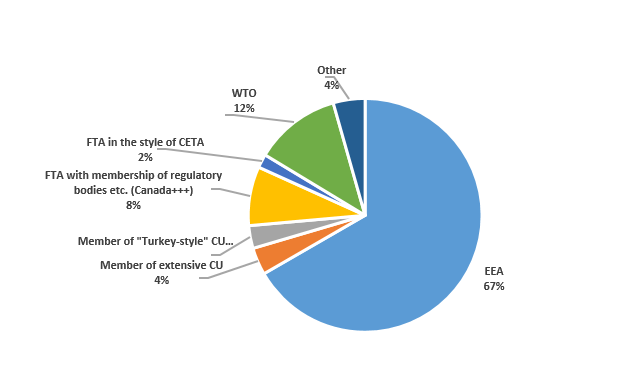

It will come as a surprise to few that members are overwhelmingly in favour of the UK remaining within the EU. Over 90% of respondents indicating that this is their preferred outcome and we can have a strong degree of confidence that the true proportion lies above 85% (a one-tailed test suggests a 0.986 probability that the interval from 85%-100% encompasses the true value). There are no significant differences between UK nationals, EU nationals and those from the rest of the world. Moreover, most RSA members feel that in the absence of EU membership, the UK should hew as closely as possible to the EU and, importantly that it should maintain freedom of movement:

Preferred Alternative to EU Membership

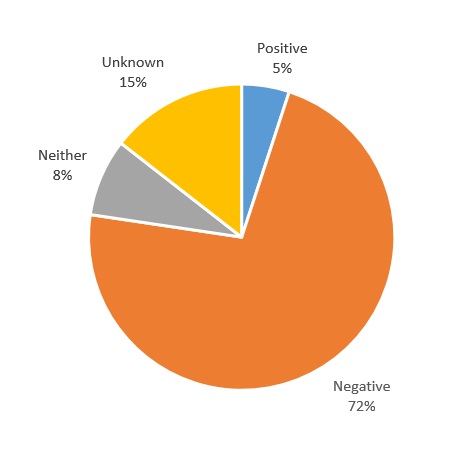

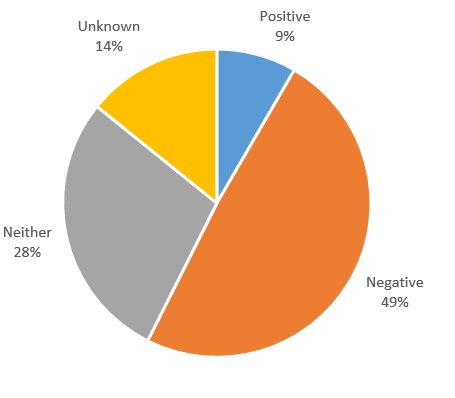

In light of the majority of evidence produced (see, e.g., Bailey & De Propris, 2017; Born, Müller, Schularick, & Sedláček, 2017; Dhingra, Ottaviano, Sampson, & Reenen, 2016; Dhingra, Ottaviano, Sampson, & Van Reenen, 2016; HM Treasury, 2016) it is unsurprising that a large majority of members felt that Brexit will have a deleterious effect on the UK economy in both the short and longer term. In a break from the academic consensus, a significant proportion of respondents did indicate both greater nuance and greater uncertainty about the long-term economic impact on the EU.

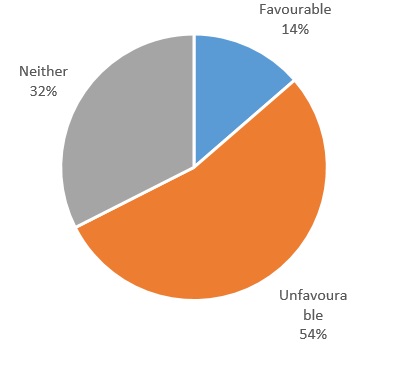

Long Term Economic Impact on the UK

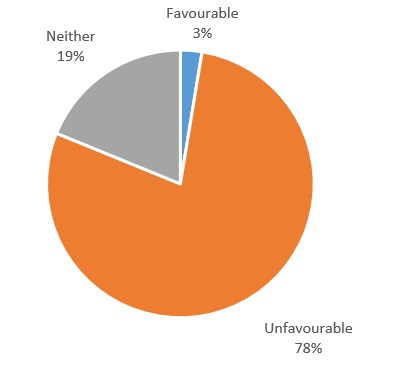

Long Term Economic Impact on the EU

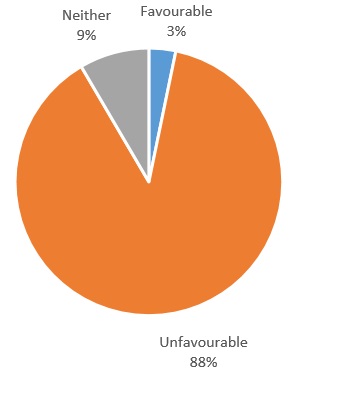

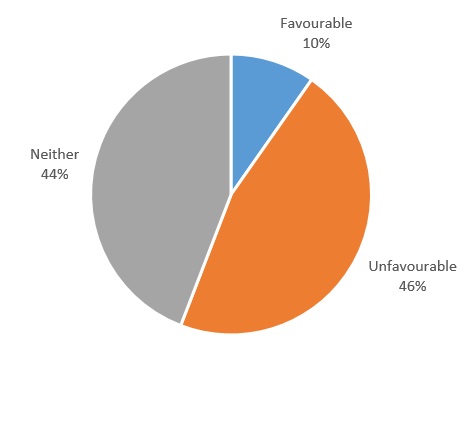

Of particular interest were respondents’ beliefs about the impact of Brexit on the Higher Education sector:

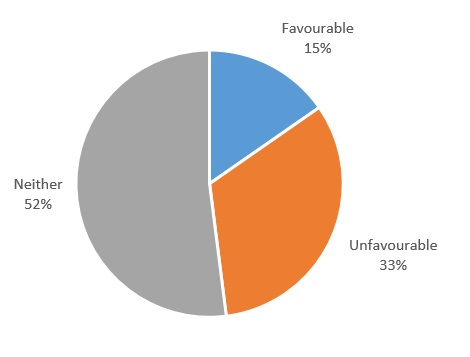

Brexit’s Impact on Research in the UK

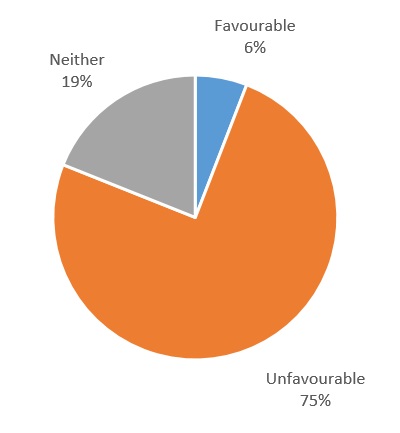

Brexit’s Impact on Research in the rest of the EU

Brexit’s Impact on Teaching in the UK

Brexit’s Impact on Teaching in the rest of the EU

Brexit’s Impact on HE Partnerships & Engagement in the UK

Brexit’s Impact on HE Partnerships & Engagement in the rest of the EU

As can be seen, a large majority of members felt that Brexit would have a negative impact on research, teaching and partnerships. Interestingly, however, there were some differences between British and European academics. Half of European academics felt that research in the EU would be negatively affected (36% felt it would be unaffected and 13% felt it would be positively affected), whilst most felt that teaching the rest of the EU would be unaffected.

More research is needed to understand what is driving these views as there are potentially competing processes at play. Whilst Brexit risks the loss of a significant funder of EU research, it also potentially takes UK institutions out of competition for that EU funding which remains. Similarly, if the impact of UK academics and students on teaching and learning in the EU was modest to begin with, it is not surprising that the impact of their loss is likely to be insignificant.

More interesting is the finding that a significant minority of respondents felt that teaching and research in the rest of the EU would actually improve post-Brexit. It would be interesting for future work to tease out exactly what processes might be at play here. In contrast UK academics were more likely to see Brexit as a lose-lose phenomenon, although around 50% agreed that teaching in the EU was likely to be unaffected as a result of Brexit.

A significant majority of respondents (some 72%) felt that Brexit would exacerbate regional disparities within the UK. Perhaps this is unsurprising given the results of published research (Chen et al., 2018; Los, McCann, Springford, & Thissen, 2017). Nevertheless, given that the Association’s membership would be expected to have an unusually high level of expertise in this field, this finding should cause concern amongst policymakers and ought to be a spur to action. Views were more mixed in terms of the impact on regional disparities in the rest of the EU, although a majority (56%) felt these would be unaffected by Brexit.

In terms of the personal impact of Brexit, 30% of members surveyed believe that Brexit will have an impact on their career. Unsurprisingly this was particularly prevalent amongst academics located in the UK with around half declaring that Brexit would affect their career. For academics located within the EU, this figure was around 21% and an overwhelming preponderance of members (64%) felt that Brexit made them less likely to work in the UK.

Members raised particular concerns about limits to freedom of movement, slower economic growth and a loss of job opportunities as well as the prospects of greater austerity. Xenophobia was mentioned a number of times as a concern, suggesting that the UK is seen as a less friendly place to settle following the vote. Finally, on a professional level, a number of respondents mentioned the potential loss of research funding as a major concern.

Implications

The survey findings confirm the great uncertainty caused by Brexit across all facets of the higher education sector. As we approach the Date of Brexit, negative perceptions about the impact of Brexit, primarily by EU academics based in the UK, will grow and UK HEIs should develop practical mechanisms for managing the actual risks to their operations and, most importantly, retention of their talent. Also in the light of the findings, there should be more focused work on how these negative perceptions will evolve and consolidate, until the full implementation of Brexit, at a regional level within the UK but also in relation to the different university groups (i.e., Russell Group, University Alliance).

Another important implication relates to wider perceptions about the UK being a less open and free country post-Brexit. Although this might not seem directly relevant to other EU countries, a potential slow-down in the activity between the UK and other EU countries will have a great impact on both sides. Further research is needed to explore these issues.

References

Bailey, D., & De Propris, L. (2017). Brexit and the UK Automotive Industry. National Institute Economic Review, 242(1), R51-R59. doi:

Born, B., Müller, G., Schularick, M., & Sedláček, P. (2017). The Economic Consequences of the Brexit Vote. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 12454.

Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS) (2018). Annual Survey results: UK business schools forging ahead despite Brexit impacts.

Chen, W., Los, B., McCann, P., Ortega-Argilés, R., Thissen, M., & van Oort, F. (2018). The continental divide? Economic exposure to Brexit in regions and countries on both sides of The Channel. Papers in Regional Science, 97(1), 25-54.

Dhingra, S., Ottaviano, G., Sampson, T., & Reenen, J. V. (2016). The impact of Brexit on foreign investment in the UK. 3.

Dhingra, S., Ottaviano, G., Sampson, T., & Van Reenen, J. (2016). The consequences of Brexit for UK trade and living standards.

Grove, J. (2018). EU academics in UK quizzed about ‘moving home’ after Brexit: Government poll condemned as insensitive. Times Higher Education.

HM Treasury. (2016). HM Treasury analysis: the long-term economic impact of EU membership and the alternatives. London: HMSO.

Los, B., McCann, P., Springford, J., & Thissen, M. (2017). The mismatch between local voting and the local economic consequences of Brexit. Regional Studies, 51(5), 786-799.

Society of Spanish Researchers in the UK. (2018). Written evidence submitted to the science & technology committee (BSI0028).

The British Academy for the Humanities and Social Sciences. (2017). Brexit means…? The British Academy’s Priorities for the Humanities and Social Sciences in the Current Negotiations.

The British Psychological Society. (2018). The Brexit Poll.

Universities UK (2018). The Brightest Minds – the vital contribution of EU staff.

Universities UK (2017). Initial Brexit deal good news for universities.