Technological Sovereignty: Protecting Citizens’ Digital Rights in the AI-driven and post-GDPR Algorithmic and City-Regional European Realm

DOI reference: 10.1080/13673882.2018.00001038

By Igor Calzada (Urban Transformations/Future of Cities, COMPAS, University of Oxford, UK)

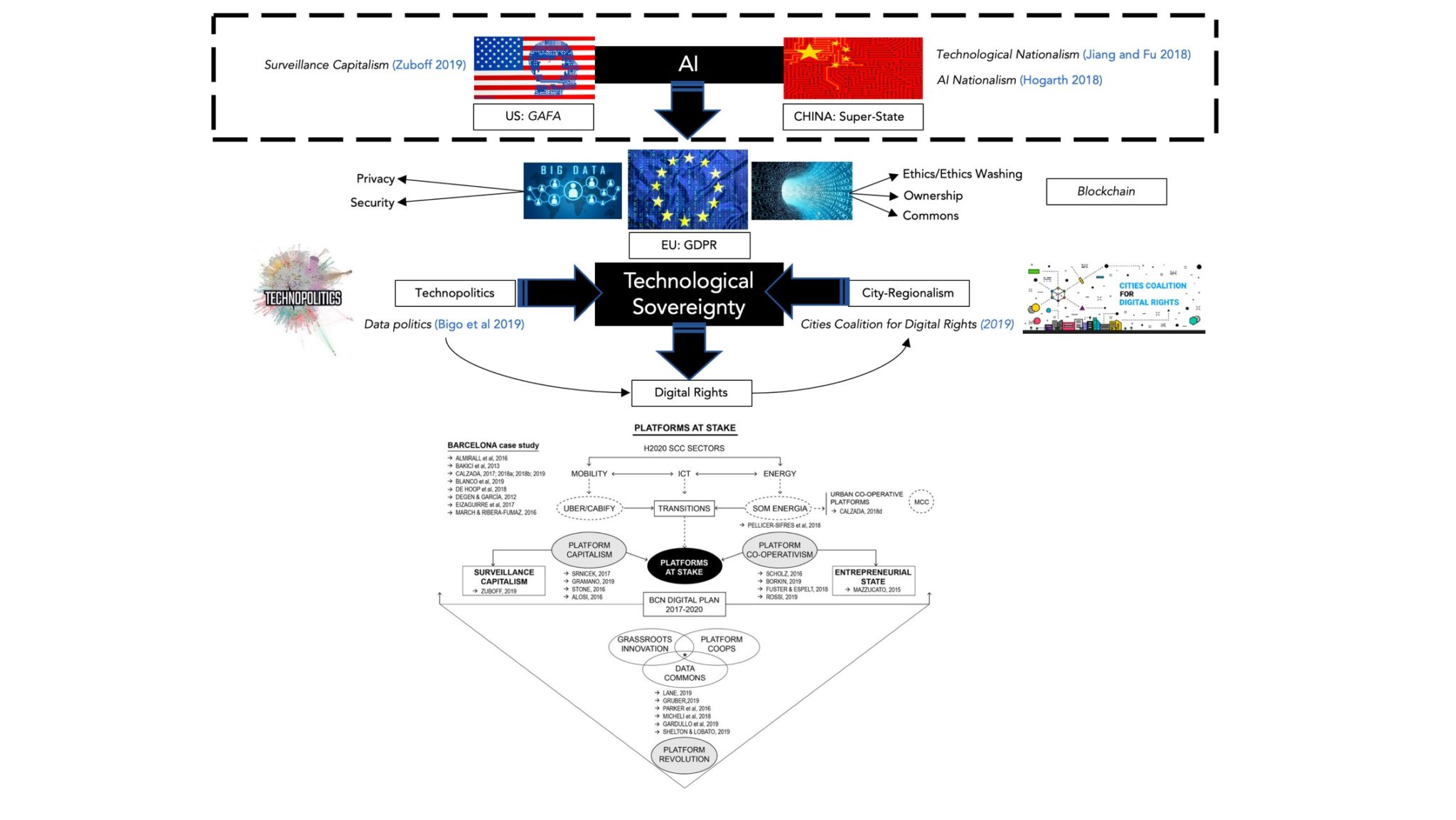

In this frontline article, blending techno-political and city-regional assemblages, Igor Calzada discusses how the algorithmic, AI (Artificial Intelligence)-driven, and post-GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) European realm affects citizenship. Drawing on evidence from previous publications, and particularly stemming from his case study of Barcelona, he builds upon a rationale through which citizens, at least in European cities and regions—unlike in the U.S. and China—are increasingly being considered decision-makers rather than mere passive data providers. He elucidates that Europe is now likely to speak with its own voice by taking the lead of the technological humanism approach, and for the first time globally by opening up an avant-garde, strategic AI overarching vision, wherein cities could federate themselves within a networked regional ecosystem and claim technological sovereignty in order to protect digital rights of their fellow citizens.

Introduction

The purpose of this article is to delineate a pervasive transitional momentum in Europe to protect citizens’ digital rights through data ownership in the aftermath of algorithmic disruption. As the profound implications of algorithmic disruption for cities and regions begin to surface around the globe, the considerable dangers and concerns regarding the hidden power of big data ‘evil geniuses’ (Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple—also known as GAFA) operating in porous regulatory systems have also come into view. As with the examples of the 2016 U.S. elections and the UK’s Brexit referendum, revelations on Cambridge Analytica’s stealthy manipulation of social media users may have performed a decisive function in shaping events of remarkable significance, thus drawing attention to the powerful social and political threats presented by increasingly sophisticated applications of big data-driven platforms (Kim et al, 2018).

Figure 1. Barcelona city, Catalonia (Spain) (i): At a glance

By contrast, in recent years, against the backdrop of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) taking effect in the European Union (EU)—and unlike the U.S. and China’s characterisation by Artificial Intelligence (AI) and data governance paradigms commanded by big tech corporations and the super-state power, respectively—a debate emerged in European cities about the role of citizens and their relationship with data (Craglia 2018; Micheli et al. 2018). This piece of research summarises and updates fieldwork research findings made since 2017 examining Barcelona as the leader of a new digital transformational agenda (Calzada 2018e) through a ‘Declaration of Cities Coalition for Digital Rights’ supported by UN Habitat (2019) and a ‘Manifesto in Favour of Technological Sovereignty and Digital Rights for Cities’ (2019). The declaration and manifesto demand technological sovereignty in cities and regions (Maurer et al. 2015) and particularly for the digital rights of citizens, mandating the ethical use of data to protect citizens from risks inherent in the disruptive, algorithmic-intensive European city-regional realm (Vesnic-Alujevic et al. 2019).

Rationale: Digital Rights and Technological Sovereignty

Smart cities globally are currently dealing with a remarkable amount of data being controlled by AI tools and devices owned by multinational corporations (Borsboom-van Beurden et al. 2019; Calzada and Cobo 2015; Goodman and Powles 2019; Green 2019). This situation raises the question of how a smart city can ensure privacy and security to its fellow citizens while experimenting with representative and deliberative democratic public expressions. In response to this question, and closely following the contours of the smart city citizenship debate, there has been a counter-reaction fuelled by the interplay of certain stakeholders, highlighting the need for an ethically transparent, data-driven society that reinforces the digital rights of citizens through accountable data ethics (Calzada 2018b). Even more recently, surveillance, privacy, anonymity, ownership, and the types of conduct that the Internet cultivates—including the so-called ethics-washing exercises (Kitchin 2019)—have been the main focus of criticism not only by critical scholars, but by an increasing number of declarations and manifestos as well. Consequently, an exploratory list may include the following 15 digital rights (Calzada 2018b):

- the right to be forgotten on the Internet;

- the right to be unplugged;

- the right to a person’s own digital legacy;

- the right of a person’s personal integrity to be protected from technology;

- the right to freedom of speech on the Internet;

- the right to a person’s own digital identity;

- the right to the transparent and responsible usage of algorithms;

- the right to have a last human instance in the expert-based decision-making processes;

- the right to equal opportunities in the digital economy;

- consumer rights in e-commerce;

- the right to hold intellectual property on the Internet;

- the right to universal access to the Internet;

- the right to digital literacy;

- the right to impartiality on the Internet;

- and the right to a secure Internet.

Paralleling the emergence of these claims on digital rights, three global paradigms are distinctively competing on data governance between one another while pervasively producing entirely different algorithmic and AI disruptive scenarios. First, in China, the state is super-rich in data and determined to put these data to use through what is known as ‘technological nationalism’, whereby large technology companies and the state embrace a mutually beneficial symbiotic relationship. Second, in the U.S., the so-called GAFA is driven by large technological private multinationals are collecting massive amounts of data from global citizens without any informed consent. Third, in Europe, the post-GDPR context is attempting to address the debate on the digital rights of citizens.

Hence, unlike the Chinese dystopian present reminiscent of an episode of the Netflix series Black Mirror, wherein companies and local governments introduce social credit rating systems that rank Chinese citizens and business, Europe seems to be aware that the more sophisticated a technology is—such as the AI defined as the capability of a machine to imitate intelligent human behaviour and Big Data—the more ‘black-boxed’ its functionality is to citizens and to scrutiny from the general public (Bodo et al. 2017). Similarly, although the ‘super star’ American model of digital innovation might be appealing, Europe is focusing on the need to start from the bottom-up to build a truly European model that is sustainable, locally-driven, regionally-rooted, and inclusive. Thus, GDPR is politically speaking timely when considering the technological, sovereignty-minded debate over controversies related to algorithmic disruption fuelled by big corporations, along with hegemonic rhetoric about the benefits of technocentric smart cities.

Indeed, the non-transparency of algorithmic governance systems is all the worse when such algorithms are fused into already-opaque governance structures (Danaher et al. 2017). Furthermore, the increasing propagation of sensors and data collection machines in both the public and private sectors raises first-time challenges concerning surveillance and defending citizens’ digital rights to privacy and ownership. The opaque nature of socio-technical assemblages and decision-making processes thereby have the potential to erode different stakeholders’ trust in multilevel city-regional governance structures and their complex decision-making processes, particularly in contexts where the outcome may be perceived as unfair or illicit. Bauman already warned that our behaviour is perpetually scrutinised by a digital watchdog, which has a chilling negative long-term side-effect on citizens. In line with this, Welsh anthropologist Raymond Williams argued that technology is never neutral. Data through technology and sovereignty through politics are inseparable.

Hence, reverting this disruptive and extractivist logic, GDPR may have already shifted the conversations that city authorities like Barcelona have with smart-city solution providers (such as Uber, Cabify, Lift, and even AirBnB), particularly in relation to their business models, monetization strategies, and data-processing procedures (Calzada and Almirall 2019a; 2019b). The case of Barcelona contrasts with the case study of Sidewalk Labs in Quayside, Toronto (Goodman and Powles 2019), an operation led by Alphabet Inc. where the tech giants’ ambition seems to bypass citizens’ consent, instead investing in broadening and deepening their surveillance techniques and becoming exploration machines that compete in innovation with a new set of economics endowed with both human and non-human logics.

Figure 2. Barcelona city, Catalonia (Spain) (ii): Rush-hour.

In this volatile scenario, as the main findings of my research revealed, Barcelona seems to have established a common ground for attempting to strike a consensus among data developers, companies, and governments on the ethics of underlying decisions in the application of digital data technology. The post-GDPR future for European cities and regions appears to be at stake insofar as recent technological developments, such as data analytics and individual profiling, have raised the level of awareness (and criticisms) of the increasing power asymmetries between big digital players, civil society, and governments. A critical perspective on data ownership combined with a socially constructed and citizen-centric smart city approach emerged in Barcelona in 2015 as a counter-reaction. Moreover, a broader movement has been initiated under the umbrella of the ‘Cities Coalition for Digital Rights,’ with its influence spreading through several European cities, including Amsterdam, Athens, Berlin, Bratislava, Grenoble, Helsinki, London, Lyon, Milan, Moscow, Tirana, Turin, Vienna, and Zaragoza. Additionally, it extends through several remarkable international cities, such as Austin, Cary, Chicago, Guadalajara, Kansas, LA, NYC, Philadelphia, Portland, San José, and Sydney.

Despite this global counter-reaction, relatively little is known about how such technological trends might actually serve the public good in terms of inspiring policy-making and the public sector. Technological sovereignty is likely to provide further insight into this pathway by designing new strategies for alternative models of data governance. As a result of this ongoing fieldwork research on Barcelona and the European model for technological sovereignty in cities and regions, I argue that we do not yet have matured, established models for sharing and adding value to data among all stakeholders (Calzada 2018c). Nonetheless, Barcelona’s experimental paradigm for technological sovereignty might have opened up the pathway for further consolidations through a federated ecosystem of cities (and regions) by putting learning processes into practice (as is the case of the EU-H2020 Replicate project among six European cities; City-to-City-Learning Programme, 2019) while preparing the fruitful strategic pathway to lead an open source platform globally beyond proprietary systems of software development.

My research concludes that Barcelona has successfully achieved its own and unique model for technological sovereignty by following these strategies: (i) explicitly addressing citizens’ needs rather than market demands alone; (ii) considering citizens as relevant actors, for example by giving them control of their personal information and letting citizens participate and collect data to use for policy-making; and (iii) using data to produce public value or urban commons (Bigo et al. 2019; Keith and Calzada 2018). Hence, technological sovereignty in European cities like Barcelona may have contributed to questioning the following aspects of: First, could cities and regions in Europe build the kind of alternatives that would put citizens back in the driver’s seat as decision-makers rather than data providers? Second, should cities and regions in Europe focus on building decentralised infrastructure like blockchain (www.ledgerproject.eu; www.eublockchainforum.eu; Allesie et al. 2019)?

Figure 3. Barcelona city, Catalonia (Spain) (iii): Streetwise, El Raval, CCCB.

Europe seems to be reaching an interesting post-GDPR algorithmic momentum. So far, Europe has somehow lacked digital leadership, reproducing policy ideas and paradigms created in other regions—as has been the case with ‘Open Data’ or the ‘City as a Platform’. This is perhaps the first time that Europe might speak with its own voice by blending avant-garde research and policy formulations beyond technocratic smart-city rhetoric (Borsboom-van Beurden et al. 2019).

Seeing Like an AI-driven post-GDPR Algorithmic and City-Regional European Realm: Through the Lenses of the Case Study of Barcelona (Catalonia)

Sovereignty is a contested term that in its Rousseauian tradition refers to a republican power derived from the people and under their control. Even more, as a result of the frenetic city-regional political context that has surrounded Barcelona since 2010, Catalonia seems to be rescaling Spain (Calzada 2018d). While the demise of the nation-state and its related post-sovereignty status is relatively clear to several scholars (Keating et al. 2019), I argue that technological sovereignty may still matter as much as cities and regions in rethinking regional Europe despite the fact that, at present, European significance in both might be rapidly shifting to a sort of algorithmic citizenship (Calzada 2018a; Couture and Toupin 2017). In this context, the positioning towards data governance has become a social and political issue not only because it concerns anyone who is connected to the Internet, but also because it reconfigures relationships between nation-states, subjects, and citizens (Bigo et al., 2019). The sovereignty of the nation-state in accumulating and generating data about citizens, health, security, or transport is being challenged by big corporations, agencies, authorities, and organisations that are producing myriad data about citizens whose interactions, transactions and movements cut across the borders of nation-states in more nuanced and pervasive assemblages (2018a).

Technological sovereignty has been used thus far as an umbrella term to suggest a spectrum of different technical and non-technical proposals, ranging from the construction of new undersea cables to stronger data protection rules. However, within the contours of the debate of this piece of research, technological sovereignty aims at breaking down the dependence on proprietary programs and encouraging public leadership through data sovereignty—safeguarding the privacy of citizens—and transparency—or constant scrutiny and auditing in the public eye. The case of Barcelona has become synonymous with the right to decide on the possibility of reproducing governance frameworks and technological artefacts that do not abuse citizens’ data by respecting them, working instead to tackle real (not only commercial) problems based on open codes. Thus, this notion of sovereignty is far from other notions like protectionism or ‘technological nationalism’ (clearly being deployed by China) that attempt (absurdly) to develop territorially-bounded and politically-predetermined technological infrastructures.

Figure 4. Board of Directors of the Barcelona City Council in the launching and participatory event of the City Data Analytics Office (#DataCommons) (Barcelona, 17th January 2018).

Against this backdrop, the AI-driven post-GDPR algorithmic and city-regional European realm has witnessed a significant strategic manoeuvre in Barcelona since 2015. My research has been following the case study of Barcelona since Ada Colau—representing the left-wing, green, social movement coalition called Barcelona en Comú—was appointed in May 2015. I have been carrying out fieldwork research through action research mixed methods (interviews, direct participation, and desk research) since 2017, examining the turning point in Barcelona’s smart city strategy through several publications and questioning whether Barcelona was establishing a sustainable paradigm in Europe by grassroots-led urban experimentation entitled ‘Data Commons’ policy framework (Calzada 2018e; Calzada and Almirall 2019a).

Since Colau’s appointment as major, Barcelona has been gradually experimenting more with shifting the smart policy agenda towards a less technocratic approach by taking on real AI-driven and post-GDPR data challenges. Yet, after the municipal elections that took place on 26 May 2019, I wonder whether the transition that started in 2015 will now be solid and sustainable enough given the victory of the independentist party Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC, Republican Left Catalonia). Although the three main parties (ERC, Barcelona en Comú, and PSC-Partit del Socialistes de Catalunya) may share a social-democratic approach towards digital rights, the future of the ‘data commons’ approach in Barcelona after the elections is likely to be uncertain due to the difficulties to reach agreements forgetting the digital value created so far. Nonetheless, despite unclear prospects for the direction of the city’s digital policy, this article highlights the remarkable contribution made so far by Barcelona in leading the European agenda towards a new digital city-regional policy agenda for Europe. The following section briefly outlines and maps Barcelona’s experimental, digital, and city-regional policy agenda, which may be used as an inspiration for other cities and regions in Europe while nourishing a federal ecosystem and willingness towards technological sovereignty protecting citizens’ digital rights.

Figure 5. Smart City Expo World Congress 2018 (#SCEWC18). Cities and regions’ stands (Barcelona, 15th November 2018).

Roadmap: Mapping Out a New Digital and City-Regional Policy Agenda for Europe

Research findings have revealed that since 2015, Barcelona has been trialling a unique policy agenda for its smart city, digital, and city-regional policy agenda, encompassing three experimental strategic initiatives in order to kick off a strategic vision based on technological sovereignty: First, the cutting-edge, innovative EU-funded projects such as DECODE led by Barcelona and Amsterdam (www.decodeproject.eu); second, the DECIDIM grassroots-led co-operative platform (www.decidim.barcelona); and, third, the METADECIDIM process for reflecting upon DECIDIM’s operations and future development through a ‘meta-lab’ of open debate (www.metadecidim.barcelona). According to several scholars, Barcelona is presently attempting to formulate and implement a different vision of a smart city and smart citizenship. What‘s more, my research discloses that Barcelona has been systematically altering socio-economic stakeholders’ structure and innovating through a new amalgamation of terms and ideas (Graph 1). This new terminological corpus was a result of a broad spectrum of stakeholders highlighting the novelty of using municipal institutions to spur a wide debate on digital rights and data ownership. Most of the interviewees agreed with the need for such a debate. A new orchestration of an active multi-stakeholder democratisation push was needed to reassert the validity of grassroots-led urban experimentation. The preliminary results of the merging of DECODE-DECIDIM-METADECIDIM, based on pilot projects in Barcelona and Amsterdam, are hybrid outcomes of technology for the signing of citizens petitions in a secure, transparent, and data-enriched manner. Thus, technological sovereignty in the case of Barcelona is characterised as a way to negotiate the technopolitics of the smart city as a contentious and dynamic process amongst several stakeholders.

In summary, Colau’s government managed to open a profound European debate on digital rights and technological sovereignty and to bring together a coalition of very strategic European and international cities, effectively restructuring European discourse about smart cities around the key idea of technological sovereignty. The final conclusion of this case study therefore shows that, through the debate about digital rights and data ownership in Barcelona (and in Europe), another metropolis was not only possible but already exists—it is waiting to be experimented with and recast as a common and co-operative good for the (smart) city itself, and, more fundamentally, for its fellow citizens.

Graph 1. Roadmap, Mapping Out a New Digital and City-Regional Policy Agenda for Europe

Figure 6. Barcelona city, Catalonia (Spain) (iv): Underground, Gràcia tube station.

Debate: Opening the Floor for Discussion

Before finalising this piece of research, which has summarised several publications and findings, I would like to open the floor for discussion by sparking a constructive debate on the challenges and threats of technological sovereignty. After GDPR turned privacy into a hot topic and the Cambridge Analytica scandal catapulted the issue of the ethics of data, city-regional authorities have been growing increasingly aware of their political and institutional power to decide on their technological sovereign share.

- How and which data can be collected and by whom?

- How can city-regional governments make policies for the digital public space?

- What happens with citizens’ data after it has been collected, or under which schemes are commercial re-use, privacy, and profits managed?

- Can a citizen decide individually to share his/her data even when it contains the data of other individuals?

- How can we strike a balance between privacy and innovation?

- Is it feasible to use procurement to enforce digital rights through ‘data commons’ frameworks?

- How can cities and regions reclaim their data in order to benefit the public good with regard to migration, residency, taxation, entrepreneurship, health, mobility, energy, or voting purposes?

- Is it feasible to attempt to overcome the barrier between the incompatibility of blockchain-based solutions and existing institutional frameworks?

- How can city-regional authorities regulate and minimise the negative side-effects of platform capitalism (Uber and AirBnB, among others); moreover, is it realistic (or wishful thinking) to establish a network of platform co-operatives across Europe?

- Ultimately, how can we unpack AI-driven applications that directly (or indirectly) affect citizens’ social, economic, and political well-being (Delponte 2018;European Commission 2018a, 2018b; European Commission and Social Committee 2019; OECD 2019; Renda 2019; Stix 2019)?

Figure 7. Barcelona city, Catalonia (Spain) (v): Streetwise, Gótico neighbourhood.

Summary

As shown through the case study of Barcelona, this piece of research depicts the key role that technological sovereignty could play by federating cities and regions in Europe into a city-regional ecosystem in order to protect citizens’ digital rights. Against the backdrop of the increasingly AI-driven world and after GDPR going into effect, there is an opportunity to further embrace a humanistic technological approach in Europe by avoiding both the American extractivist model led by big tech firms and the Chinese ‘technological nationalistic’ model exercised through social credit systems as a technique of algorithmic social control run by the state. Beyond so-called data privacy and security—bypassing ethics washing exercises even further —unlike in the past, Europe can now lead and speak with its own voice in protecting citizens’ digital rights by developing real data ownership policies in a unique fashion. By following the pathway trail-blazed by Barcelona, among others, Europe can attempt to initiate a voluntarily-federated ecosystem made up of a diverse set of cities and regions.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are extended to those who have assisted the author during his fieldwork research in Barcelona and Catalonia.

References

Allesie D, Sobolewksi M, Vaccari L, and Pignatelli F (Ed) (2019) Blockchain for digital government. EUR 29677 EN. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Bigo D, Isin E, and Ruppert E (2019), Data Politics, London: Routledge.

Bodo B, Helberger N, Irion K, Zuiderveen Borgesius F, Moller J, van de Velde B, Bol N, van Es B, and de Vreese C (2017) ‘Tackling the algorithmic control crisis-the technical, legal, and ethical challenges of research into algorithmic agents’, Yales JL & Tec, 19(133).

Borsboom-van Beurden J, Kallaos J, Gindroz B, Costa S, and Riegler J (2019) Smart City Guidance Package: A Roadmap for Integrated Planning and Implementation of Smart City projects. Brussels: EIP-SCC.

Calzada I (2015) ‘Benchmarking future city-regions beyond nation-states’, Regional Studies, Regional Science, 2(1), 351-362.

Calzada I (2018a) ‘‘Algorithmic nations’: seeing like a city-regional and techno-political conceptual assemblage’, Regional Studies, Regional Science, 5(1), 267-289.

Calzada I (2018b) ‘Deciphering Smart City Citizenship: The Techno-Politics of Data and Urban Co-operative Platforms’, Revista International de Estudios Vascos, RIEV, 63(1-2), 00-00.

Calzada I (2018c) ‘From Smart Cities to Experimental Cities?’, in V. M. B. Giorgino & Z. Walsh (eds), Co-Designing Economies in Transition: Radical Approaches in Dialogue with Contemplative Social Sciences, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 191-217.

Calzada I (2018d) ‘Metropolitanising small European stateless city-regionalised nations’, Space and Polity, 22(3).

Calzada I (2018e) ‘(Smart) Citizens from Data Providers to Decision-Makers? The Case Study of Barcelona’, Sustainability, 10(9), 3252.

Calzada I and Almirall E (2019a) Barcelona’s Grassroots-led Urban Experimentation: Deciphering the ‘Data Commons’ Policy Scheme. Paper presented at the Data for Policy 2019, London.

Calzada I and Almirall E (2019b) Is Barcelona establishing a sustainable paradigm in Europe by grassroots-led smart urban experimentation through the ‘data commons’ policy? Paper presented at the American Association of Geographers Annual Meeting 2019, Washington DC.

Calzada I and Cobo C (2015), ‘Unplugging: Deconstructing the smart city’, Journal of Urban Technology, 22(1), 23-43.

Manifesto In Favour of Technological Sovereignty and Digital Rights for Cities (2019)

European Commission (2018a) The European AI Landscape. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission (2018b) Ethics Adivsory Group – Report 2018. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission and Social Committee (2019) Artificial Intelligence for Europe. Position Paper.

Declaration of Cities Coalition for Digital Rights (2019)

City-to-City-Learning Programme, Replicate EU (2019)

Couture S and Toupin S (2017) What Does the Concept of ‘Sovereignty’ Mean in Digital, Network and Technological Sovereignty? Paper presented at the Giganet 2017 Conference.

Craglia M (Ed) (2018) Artificial Intelligence: A European Perspective. Luxembourg: Publications Office.

Danaher J, Hogan M J, Noone C, Kennedy R, Behan A, Paor A D, Felzmann H, Haklay M, Khoo S-M, Morison J, Murphy M H, O’Brolchain N, Schafer B and Shankar, K. (2017) ‘Algorithmic governance: Developing a research agenda through the power of collective intelligence’, Big Data & Society, 4(2).

Delponte L (2018) European Artificial Intelligence (AI) Leadership, the path for an integrated vision. Brussels: ITRE-Committee European Commission.

Goodman E P and Powles J (2019) ‘Urbanism Under Google: Lessons from Sidewalk Toronto’, Fordham Law Review.

Green B (2019) The Smart Enough City: Putting Technology in Its Place to Reclaim Our Urban Future, Boston: MIT Press.

Keating M, Jordana J, Marx A, and Wouters, J (2019) ‘States, sovereignty, borders and self-determination in Europe’, in J. Jordana, M. Keating, A. Marx, & J. Wouters (eds), Changing Borders in Europe: Exploring the Dynamics of Integration, Differentiation and Self-Determination in the European Union, London and NYC: Routledge/UACES Contemporary European Studies, pp. xii-18.

Keith M and Calzada I (2018) Back to the “Urban Commons”? Social Innovation through New Co-operative Forms in Europe. Brussels.

Kim Y M, Hsu J, Neiman D, Kou C, Bankston L, Kim S Y, Heinrich R, Baragwanath R and Raskutti G (2018) ‘The stealth media? Groups and targests behind divisive issue campaigns on Facebook’ Political Communication, 35(4), 515-541.

Kitchin R (2019) ‘The ethics of smart cities’

Maurer T, Skierka I, Morgus R, and Hohmann M (2015) Technological Sovereignty: Missing the Point? Paper presented at the 2015 7th International Conference on Cyber Conflict: Architectures in Cyberspace, Tallinn.

Micheli M, Blakemore M, Ponti M, and Craglia M (2018) The Governance of Data in a Digitally Transformed European Society. Ispra: European Commission. DOI: JRC114711.

OECD (2019) ‘OECD moves forward on developing guidelines for artificial intelligence (AI)’

Renda A (2019) Artificial Intelligence: Ethics, governance and policy challenges. Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS).

Stix C (2019) A survey of the European Union’s artificial intelligence ecosystem. Cambridge: Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence.

Vesnic-Alujevic L, Stoermer E, Rudkin J, Scapolo F, and Kimbell L (2019) The Future of Government 2030+: A Citizen-Centric Perspective on New Government Models. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.