SME Resilience during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Exploring Urban-rural differences

DOI reference: 10.1080/13673882.2021.00001103

By Dafydd Cotterell and Dr Robert Bowen, School of Management, Swansea University

The Covid-19 pandemic – and subsequent lockdown policies established across much of the world – created unprecedented change for commercial organisations, with many businesses encouraging staff to work from home, placing staff on furlough and evoking redundancies. Furthermore, social distancing laws and restrictions on social gatherings meant that many businesses were obliged to close or adapt their operations during the trans-crisis stage. The sudden changes to business operations created challenges for many businesses, especially for resource-constrained Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), testing their ability to survive and adapt to the new environment. This paper investigates business resiliency in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, considering whether differences exist between urban and rural SMEs. The paper draws on a growing body of literature relating to crisis management and resilience before discussing evidence from the UK.

Managing crisis in SMEs

The subjectivity of the term crisis creates much ambiguity in the crisis literature with no universally accepted definition for the term in a business management context (Coombs, 2012). Crisis can be considered as part of a lexicon of terms describing negative events impacting on business operations. Other terms synonymous with crisis include business malfunctions, accidents, disasters, failure or serious incidents. This has led to an academic discussion in the literature seeking to decrease the subjectivity of the term crisis and present a definition. Two literal perspectives can be observed; one that seeks to separate the term crisis from terms such as disaster (Laws & Prideaux, 2005), and another which seeks to define a crisis as any event that is extreme, unexpected or unpredictable, that creates challenges for the organisation and requires an urgent response to minimise business losses (Doern et al. 2019). One of the most widely accepted and adopted definitions can be seen to accept the later conceptualisation defining a crisis as a low probability, high impact situation that requires the organisation to take action in some way (Pearson & Clair, 1998).

The Covid-19 pandemic can be seen as a macro-sized crisis that has created far-reaching implications and ramifications for economies across the globe, including that of the UK economy (Nicola et al. 2020). Covid-19 as an organisational crisis conforms with the most widely accepted crisis conceptualisation; a low probability, high impact situation that requires key stakeholders to take action in some way, under a perceived or real time constraint (Pearson & Clair 1998). Crisis studies in an SME context exist in a relative paucity, with the majority of studies within the field concerning larger more complex organisations (Herbane, 2013). SME crisis studies adopt two key conceptualisations for the effective mitigation of crisis events, crisis management and organisational resilience (Doern et al. 2019). Williams et al. (2018) differentiate these concepts by suggesting that the crisis management approach concerns the ability of actors to bring a weakened system (i.e. organisation) back into alignment, whereas organisational resilience studies the ability of an organisation to maintain reliable functioning throughout a period of disruption. To date, a relatively small number of crisis studies concerning Covid-19 in an SME context have been published. These studies predominantly examine SME and entrepreneur behaviours in the early stages of Covid-19. Kuckertz et al. (2020) examined the response of start-ups in the early stages of Covid-19 and found that the effective bricolage of resources proved an effective form of organisational resilience to the pandemic, adding to the already rich academic precedent behind bricolage as an effective crisis mitigating activity (cf. Gilbert-Saad, Siedlok, & McNaughton, 2018; Martinelli, Tagliazucchi, & Marchi, 2018; Brunjes & Revilla-Diez, 2013). In another study conducted by Thorgren & Williams (2020) the financial behaviours of SMEs during the pandemic were examined. The study identified a change in financial behaviour with small businesses engaging in cost cutting activities, a previously observed behaviour during times of crisis (Smallbone et al, 2012). Such literature has not, however, considered disparities in firm performance across urban and rural centres.

While the Covid-19 pandemic is an unprecedented crisis event in modern times, crisis literature points to various natural disasters, diseases and manmade incidents as previous events that have impacted on the ability of SMEs to maintain normal functioning. Such studies include small business response to Hurricane Katrina in the area around New Orleans, Louisiana, US in 2005 (Runyan 2006), the 2011 Christchurch earthquake in New Zealand (de Vries & Hamilton, 2021), and the 2011 London Riots (Doern, 2016). The 2008 Global Financial crisis proves comparatively similar to Covid-19 in the respect that it can be viewed as a fundamental crisis through the lens of Gundel’s (2005) typology matrix; an event that was difficult to predict and impact at a firm level. Smallbone et al. (2012) observed that while many SMEs were vulnerable to change caused by the crisis, they also displayed resilience through high levels of flexibility and adaptability, notably through cost-cutting and revenue-generating activities. Additionally, the 2001 Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) crisis in the UK offers lessons in the impacts of an epidemic on the rural economy, albeit an animal disease epidemic. Irvine and Anderson (2004) highlight the use of regional restrictions in the movement of livestock as a means of limiting FMD spread, which affected the ability of local businesses to operate, and negatively impacted levels of tourism across Cumbria and the Grampians, where tourism businesses explored substitute products in order to develop resilience.

SME Resilience in the UK

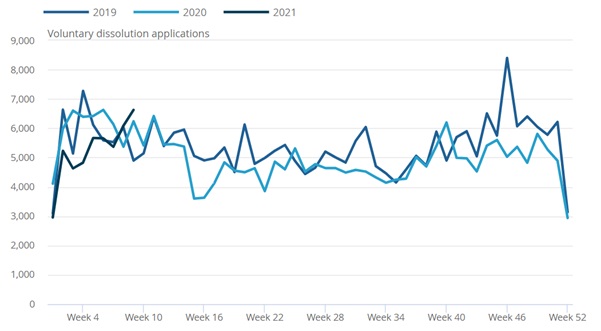

Despite the challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic, data from the Office of National Statistics (ONS) in the UK point to the resilience of businesses. This can be, in part, highlighted through comparing business dissolution and registration data during the pandemic to levels in 2019 (pre-crisis stage). Figure 1 outlines that company dissolution applications remained lower than levels of 2019 throughout the majority of the Covid-19 pandemic restrictions (beginning in March 2020).

Figure 1: UK Business Dissolution Applications

Source: ONS (2021)

Similarly, as displayed in Figure 2, higher levels of company incorporations were observed across 2020 and 2021 when compared to 2019. This is especially true from mid 2020 onwards, after the easement of first wave restrictions, with higher levels of new business registrations continuing throughout the height of the second wave during the first part of 2021.

Figure 2: UK New Company Registrations

Source: ONS (2021)

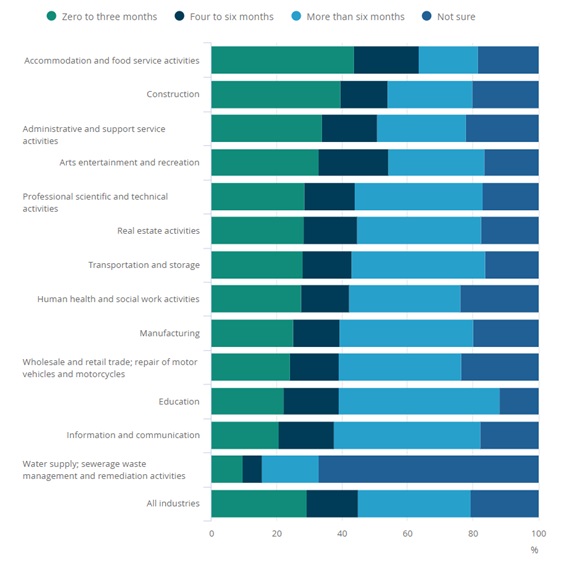

Findings in Figures 1 and 2 underline that although many businesses ceased operations during the Covid-19 pandemic, this occurred at a lower rate than in 2019, which implies that support measures, such as placing staff on furlough, and enabling staff to work from home, allowed many businesses to continue to operate across the trans-crisis stage. The increased level of new business registrations implies an increased level of entrepreneurial activity compared to 2019 levels. While general business resilience could be observed from the above data, differences exist across sectors. Figure 3 outlines the resilience of businesses in different sectors through evaluating the length of cash reserves among trading businesses. Findings show that accommodation and food services have the highest level of responses in the zero to three months category, highlighting the precarity seen in the hospitality sector due to businesses pausing or significantly reducing trade. The construction sector also expressed limited reserves, followed by administration and support service activities, and arts entertainment and recreation.

Figure 3: Cash Reserves by Sector (October to November 2020)

Source: ONS (2020)

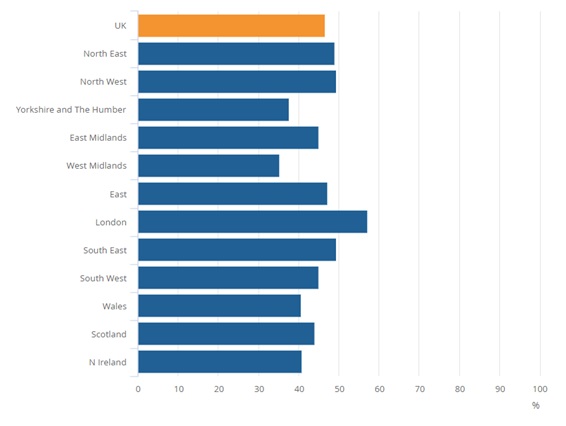

Tourism and hospitality are sectors that have been among the most impacted by the introduction of lockdown and social distancing regulations, limiting the ability of such businesses to remain open, and to trade at profitable levels of capacity, impacting many rural areas, such as coastal areas and national parks, where tourism is prominent. The nature of tourism and hospitality businesses limits the ability of such businesses to implement home working business model optimisations. When observing spatial data, levels of employees working from home during the height of the first wave of pandemic restrictions can be seen at their highest within the London region, with lower levels observed for the largely rural regions of Yorkshire and the Humber, the West Midlands, Wales and Northern Ireland (Figure 4). A survey of attitudes towards homeworking conducted in 2021, showed that respondents in rural areas expressed that they were less likely to return to work within the next two months, compared to respondents in urban areas.

Figure 4: Homeworking rates by UK Region, April 2020

Source: ONS (2020)

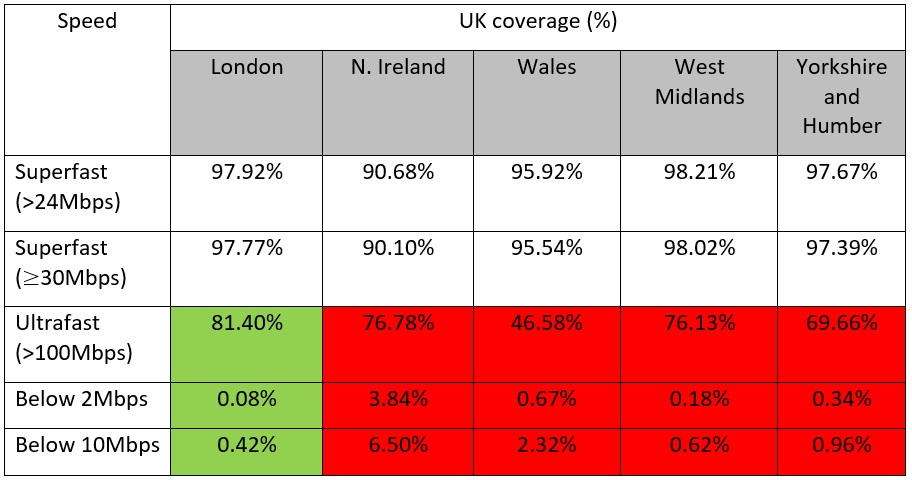

Further data from Thinkbroadband.com, outlined in Figure 5, suggests how these predominantly rural regions might also be falling behind the London region due to lower percentages of the population having access to ultrafast internet, while also having higher percentages of the population still receiving internet speeds below two and ten Mbps.

Figure 5: Broadband speeds across UK regions.

Source: Generated from Thinkbroadband.com data (2021)

While key industries in rural areas, such as tourism and hospitality, have been more impacted by Covid-19 regulations, there is optimism that the easing of restrictions seen in July and August 2021 could lead to a more rapid recovery, especially as domestic tourism levels increase during the summer of 2021, while international travel remains uncertain. This includes areas of Wales, Cornwall and Cumbria.

Rural SME Resilience

Previous crises have shown that rural economies can be resilient and adaptable (Philipson et al. 2021), most notably the 2001 FMD Crisis, in which many control measures seen during the Covid-19 pandemic, such as restrictions in movement, isolation, and testing, were employed on the animal population to prevent the spread of the disease. During the FMD crisis, rural businesses were able to become more resilient through pluriactivity. As with previous related crises, businesses have shown during the Covid-19 pandemic that they can adapt their business activities to work under new regulations, and become more entrepreneurial, however, there is a question over how resilient rural small businesses can be. Many businesses during the Covid-19 pandemic showed adaptability in diversifying their business activities in order to remain in operation. This was seen through bars and restaurants offering take-away services, or local shops selling products online, however, these diversified activities are often reliant on access to fit for purpose internet in order to facilitate marketing and logistical operations. Access to sufficient internet connectivity is considered a valuable resource, yet concerns are raised that some rural businesses, particularly SMEs, are disadvantaged due to limited and often no access to the internet in some hard to reach areas. Philipson et al. (2021) note that limited broadband access may impact on business activities, remote working, and the ability for businesses to apply for support, which is conducted through an online application. Further impacts of poor broadband connectivity on rural businesses are seen on the ability to engage in face-to-face interactions online, as well as the businesses’ abilities to conduct basic business operations such as efficiently managing their sales, customer service, social media and payments. These challenges experienced by rural businesses supports discussions relating to a digital divide.

A UK Digital Divide

A digital divide can be defined as “a situation where a discrete sector of the population suffers significant and possibly indefinite lags in its adoption of information and communication technologies (ICT) through circumstances beyond its immediate control” (Warren 2007, p.375). This phenomenon is commonly considered from two perspectives, one that considers connective infrastructure and another that considers the degree to which persons are included within the digital society (Salemink et al. 2017). The digital divide debate can be seen to have evolved from an argument of haves and have nots to an argument concerning Next Generation Access technologies (NGA). Digital connectivity is considered important in facilitating business start-ups (Audretsch et al., 2015) and enabling entrepreneurship (Alderete, 2017). Indeed, research by Bowen and Morris (2019) concluded that broadband access issues in rural areas in Wales led to local SMEs becoming more passive towards growth opportunities, limiting the ability for rural SMEs to engage in more diversified activities. The authors also state that failure to address such divisions between urban and rural areas leads to the risk of a ‘brain drain’ and loss of skilled people from rural to urban areas. The value of digital connectivity to rural areas is further underlined by Townsend et al. (2013), who recognise broadband access as a key enabler to a range of business activities. Limited digital connectivity, notably in rural areas, could therefore constrain the opportunities for businesses to conduct fundamental business activities, and diversify their business model.

Conclusion

The Covid-19 pandemic has brought numerous challenges for businesses across a range of sectors. Despite this, findings imply that businesses in the UK have shown resilience in surviving the difficulties of periods of lockdown. This has been achieved through support and the ability to be flexible in diversifying the business activity, with access to broadband internet acknowledged as a valuable resource in enabling businesses to apply for financial support, retain employees working at home, and engage in new business activities, such as selling products online. While businesses have managed to survive, the lasting impacts of lockdown regulations were more prominent in the tourism and hospitality sectors, where businesses remained closed for longer period of time, employees were less able to work from home, and businesses were constrained by limited capacity, once re-opened, due to social distancing. These businesses are prominent in rural areas, where limited access to internet is also more evident, and has the ability to affect the entrepreneurial capacity for businesses. This underlines the need to address rural-urban differences in broadband activity, and end the digital divide.

References

Alderete, M. V. (2017). Mobile Broadband: A Key Enabling Technology for Entrepreneurship? Journal of Small Business Management, Vol 55, No 2, 254–269.

Audretsch, D. B., Heger, D., & Veith, T. (2015). Infrastructure and entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, Vol 44, No 2, 219–230.

Bowen, R., & Morris, W. (2019). The digital divide: Implications for agribusiness and entrepreneurship. Lessons from Wales. Journal of Rural Studies, 72, 75–84.

Brünjes, J., & Revilla-Diez, J. (2013). Recession push’ and ‘prosperity pull’ entrepreneurship in a rural developing context. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, Vol 25, pp. 251–271.

Coombs, W. T. (2015). Ongoing Crisis Communication, 4th ed. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

De Vries, H., & Hamilton, R. (2021). Smaller businesses and the Christchurch earthquakes: A longitudinal study of individual and organizational resilience. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, Vol 56, e102125.

Doern, R. (2016). Entrepreneurship and crisis management: The experiences of small businesses during the London 2011 riots. International Small Business Journal, Vol 34, No 3, pp. 276-302.

Doern, R., Williams, N., & Vorley, T. (2019). Special issue on entrepreneurship and crises: business as usual? An introduction and review of the literature. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, Vol 31, No 5-6, pp. 400-412.

Gilbert-Saad, A., Siedlok, F., & McNaughton, R. (2018). Decision and design heuristics in the context of entrepreneurial uncertainties. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, Vol 9, pp. 75–80.

Gundel, S. (2005). Towards a new typology of crises. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, Vol 13, No 3, pp. 106-115.

Herbane, B. (2013). Exploring crisis management in UK small- and medium-sized enterprises. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, Vol 21, No 2, pp. 82–95.

Irvine, W., & Anderson, A. (2004). Small tourist firms in rural areas: Agility, vulnerability and survival in the face of crisis. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research Vol 10, No 4, pp. 229–246.

Kuckertz, A. L., Brandle, A., Gaudig, S., Hinderer, C. A., Morales Reyes, A., Prochotta, K. M. Steinbrink, K. M., & Berger, E. S. C. (2020). Start-ups in times of crisis – a rapid

response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, Vol 13, e00169.

Laws, E., & Prideaux, B. (2005). Crisis management: a suggested typology. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, Vol 19, pp. 1–8.

Martinelli, E., Tagliazucchi, G., & Marchi, G. (2018). The Resilient Retail Entrepreneur: Dynamic Capabilities for Facing Natural Disasters. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, Vol 24, No. 7, pp. 1222-1243.

Nicola, M. Alsafi, Z. Sohrabi, C. Kerwan, A. Al-Jabir, A. Iosifidis, C., Agha, M., & Agha, R. (2020). The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. International journal of Surgery, Vol 78, pp. 185-193.

Pearson, C. M. & Clair, J. A. (1998). Reframing crisis management. Academy of Management Review, Vol 23, pp. 59–76.

Phillipson, J., Gorton, M., Turner, R., Shucksmith, M., Aitken-McDermott, K., Areal, F., Cowie, P., Hubbard, C., Maioli, S., McAreavey, R., & Shortall, S. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and its implications for rural economies. Sustainability, Vol 12, No 10, 3973.

Runyan, R.C. (2006). Small business in the face of crisis: Identifying barriers to recovery from a natural disaster. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, Vol 14, pp. 12–26.

Salemink, K., Strijker, D., & Bosworth, G. (2017). Rural development in the digital age: A systematic literature review on unequal ICT availability, adoption, and use in rural areas. Journal of Rural Studies, 54, pp. 360–371.

Smallbone, D., Deakins, D., Battisti, M., & Kitching, J. (2012). Small Business Responses to a Major Economic Downturn: Empirical Perspectives from New Zealand and the United Kingdom. International Small Business Journal, Vol 30, No 7, pp. 754–777.

Thorgren, S., & Williams, T. A. (2020). Staying alive during an unfolding crisis: how SMEs ward off impending disaster, Journal of Business Venturing Insights, Vol 14, e00187.

Townsend, L., Sathiaseelan, A., Fairhurst, G., & Wallace, C. (2013). Enhanced broadband access as a solution to the social and economic problems of the rural digital divide. Local Economy, Vol 28, No 6, pp. 580–595.

Warren, M. (2007). The digital vicious cycle: Links between social disadvantage and digital exclusion in rural areas. Telecommunications Policy, Vol 31, pp. 374–388.

Williams, T. A., Gruber, D., Sutcliffe, K., Shepherd, D., & Zhao, E. (2017). Organizational Response to Adversity: Fusing Crisis Management and Resilience Research Streams, Academy of Management Annals Vol 11, No 2, pp. 733–769.