By Naomi Hazarika, National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration, New Delhi, India

This article throws light on the dynamics of urban redevelopment involving the opening up of state lands for private investment where informal settlements are located in the city of Delhi, India, using the conceptual tool of a ‘real estate frontier’ (Gillespie, 2020). This is done through the study of a policy of slum redevelopment called “In-Situ Slum Redevelopment and Rehabilitation on Public-Private Partnership model 2019 (ISSR)” implemented by Delhi Development Authority (DDA).

Justified by the Delhi Development Authority as the ‘ proper utilization of vacant/encroached land parcels of DDA/Central Government agencies/Departments’, this redevelopment policy, when juxtaposed with its viability and associated effects such as the limited capacity of citizens to engage, participate and claim welfare from the state, raises important questions regarding the priorities that underline urban governance and state investment. In this article, the policy is contested on two major grounds, the inaccurate portrayal of slums as ‘encroaching’ over a large part of the city, and the undemocratic nature of the implementation of this policy. Through this, the article highlights the need to unpack state decisions and policies that push for certain types of redevelopment projects as part of an increasingly financialised process of urban transformation, and demystify who or which class stands to benefit from such projects that have reasons to be unviable on many accounts.

Housing accessibility and affordability in India

India has embarked on a mission to ensure housing for all by the year 2022. The Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana-Urban (Prime Minister’s Housing Policy- Urban) introduced on the 1st of June 2015, marks one of the most ambitious projects of the country to provide affordable housing to the urban poor. One of the four verticals of the ‘Housing for All by 2022 Mission’, under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (Prime Minister’s Housing Policy), is that of “In situ” Slum Redevelopment using “land as a resource” (Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation, 2015 p. 2). This includes the private participation of developers for providing houses to eligible slum dwellers through the construction of high rise apartments where the slums are located today.

In order to align state policy with the national housing mission, the Delhi Development Authority has passed a policy called ‘In-Situ Slum Redevelopment and Rehabilitation on Public-Private Partnership model 2019’ (henceforth referred to as ISSR 2019) with a vision to make the city of Delhi slum-free by 2022. Modelled on the Masterplan for Delhi 2021, the Policy states that each redevelopment project shall have a maximum of 40% of the land reserved for remunerative purposes for the private developer involved, while 60% of the land has to be used for in-situ redevelopment to rehabilitate slum dwellers. Under this policy, as of 21st January 2020, detailed project reports have been made for the redevelopment of 16 settlements and surveys are being carried out in 160 settlements in Delhi, India.

In this article, slum redevelopment projects under ISSR 2019 are understood as creating a ‘real estate frontier’ (Gillespie, 2020) to highlight the process of incremental commodification of state lands in Delhi, where ‘slums’ or ‘Jhuggi-Jhopdi Clusters’ are located, housing a large number of people. In doing so, it underscores an active state prioritization of catering to private capital and interests over upgrading existing housing or ensuring basic service delivery for citizens residing in these informal settlements. It further questions the use of ISSR 2019 as a policy to redevelop and rehabilitate residents of informal settlements or ‘slums’ on two major grounds. First, the misrecognition of residents as ‘encroachers’ over a large amount of prime land in the city when data proves otherwise. Secondly, the policy plays an active role on the exclusion of the residents in the process of decision-making which directly affects their lives. Overall, the article highlights the role of the state and the need to unpack state decisions and policies that push for certain types of redevelopment projects and demystify who or which class stands to benefit from such projects that have reasons to be unviable on many accounts.

Real-Estate Frontiers in Accra and Delhi

Postcolonial scholarship on urbanism stresses the universalizing tone of dominant theories of urban redevelopment and displacement such as gentrification (Ghertner, 2014) or speculative urbanism. It further suggests a focus on the contextual processes and accounts of diverse realities as seen in cities of the global south (for a thorough reading on the debate between postcolonial theory versus planetary urbanism to study southern urbanism, refer to Schindler (2017)) (Parnell and Robinson, 2012; Robinson, 2016; Roy, 2009, 2016; Ghertner, 2020). Gillespie (2020) offers an original concept of a ‘real-estate frontier’ to understand the process of urban redevelopment in Accra, Ghana as a response to the failure of existing theories to sufficiently explain these transformations and ‘generate new, alternative concepts’ from the global south (p.2). Gillespie draws on the concept of ‘commodity frontiers’ (Moore, 2000; 2015; Schindler and Kanai, 2018) and ‘gentrification frontier’ (Smith, 1996) to understand how capitalism expands geographically through local zones of uncommodified resources.

The theoretical merit of a ‘real-estate frontier’, employed to explain the dynamics of urban redevelopment in the context of slum redevelopment is twofold. Firstly, it begins with the understanding that it is the capture of new urban spaces in the form of state-owned lands instead of already commodified spaces in cities where private interests and capital are increasingly involved. Secondly, it draws our attention towards the role of the postcolonial history of state land acquisition and urban planning in dictating the terms of contemporary urban redevelopment.

The processes of urban redevelopment and land privatization of state lands in Accra and Delhi are shockingly similar on various accounts. The policy of ‘In-situ Slum Rehabilitation and Redevelopment in PPP model’ of the Delhi Development Authority and the policies adopted by the government in Ghana both incentivize private developers to participate in the process of redevelopment in exchange for equity shares of the developments on the sites. More importantly, both governments mention using land as a resource, whether it is the “leveraging of land resources” in Accra (Gillespie, 2020 p.10) or the “…proper utilization of vacant/encroached land parcels of DDA/Central Government agencies/Departments” in the case of the policy in Delhi (Delhi Development Authority, 2019, p.89). In the process of which, as Gillespie (2020, p.15) argues, “the advancement of the real estate frontier is enabled by the discursive framing of state lands as underutilized and degraded to justify their enclosure”. Similarly, slum evictions in Delhi are often justified on a reductionist understanding of the land on which these settlements are located by using terms such as ‘illegal’ or ‘encroachments’ instead of recognizing that these are incrementally built auto-constructed houses that have been the direct result of state failure to provide affordable housing to all (Bhan et.al., 2020).

This policy response driven by the logic of removing well-established settlements in favour of using land as a resource through ISSR is unjust and uproots the lives of many citizens. In the following section I highlight two major grounds on which the implementation of ISSR for the redevelopment of informal settlements in Delhi can be contested.

‘Slums’ as large encroachments

As mentioned above, the land on which informal settlements (particularly Jhuggi-Jhopdi Clusters or JJCs) are located in the city of Delhi are often referred to as encroachments over ‘prime locations’ (Delhi Development Authority, 2020) in policy and legal documents which is then used to sanction evictions or redevelopment projects. However, a recent spatial assessment on these ‘slums’ carried out by the Indian Institute of Human Settlements (Bhan. et.al., 2020) revealed that despite the language of encroachment and the sense of wide spread land grabs, ‘slums’ or ‘Jhuggi Jhopdi Clusters’ occupy a minute portion of land in the city. This is no more than 0.6% of the total land area and no more than 3.4% of land which is zoned for residential use in Delhi Masterplan 2021. More importantly, this minute portion of land is where a large percentage of the city’s population (no less than 11%-15% but possibly up to 30%) reside in their auto-constructed homes of varied physical and infrastructural types.

Using factually inaccurate notions of ‘encroachment’ of a very small portion of land, policies of redevelopment such as ISSR necessarily involve the demolition of existing housing and resettlements that have been proven to destroy livelihoods and negatively impact generational improvement. Considering this, therefore, important questions must be raised to ask why policy-makers are pushing for this model of redevelopment projects for a small portion of land. Are the interests of residents of these settlements kept in mind while devising these solution? Who or which class is ultimately benefitting from this policy?

‘No-Consent Required’: Denial of rights and dignity

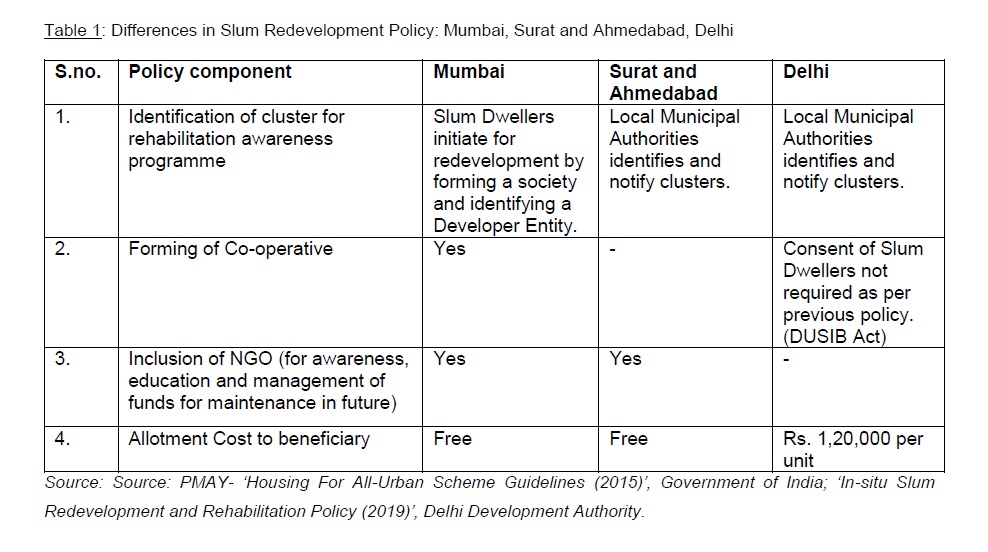

Slum redevelopment and rehabilitation schemes involving private developers are certainly not a new phenomenon in the context of India. In Mumbai, the Slum Redevelopment Schemes (SRS) were implemented as early as 1991 involving private developers in construction while the role of the government was only restricted to that of regulation (Mahadevia, 2018; Mukhija, 2001).

Around a decade ago, in 2009, the national housing policy called ‘Rajiv Awas Yojana (RAY)’ allowed for slum redevelopment projects across the country based on a Public-Private Partnership model as and when required. So, what is different about the ‘In-situ Slum Redevelopment and Rehabilitation Policy on PPP model’ to be implemented in the city of Delhi?

The primary difference between the range of slum redevelopment and rehabilitation policies that have been implemented across four major Indian cities is the exclusionary denial of any actual engagement with, and the participation of, the residents of the settlements involved in the projects. For example, in the case of Mumbai, a private developer is allowed to propose a plan for redevelopment or rehabilitation of a particular slum area only when they have 70% written consent of the slum dwellers living in that area (Bhide, 2015). The policy in Mumbai allowed the space for slum dwellers to come together and form a ‘society’ in order to identify and initiate a redevelopment project with a private entity.

Moreover, it is clearly mentioned in the policy document published by the Delhi Development Authority (2019), that “Consent of the Jhuggi-Jhopdi (slum) dwellers for ISSR (In-Situ slum redevelopment) is not required as per section 10 of the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board Act.”

In Kusumpur Pahari, for example, situated on prime real estate land in South Delhi and the largest settlement slated to be redeveloped under this policy, there has been little to no interaction between officials of the Delhi Development Authority and the residents apart from the local leader (or Pradhan). Due to this lack of transparency, all residents do not have full information about the course of the redevelopment project and the process of rehabilitation (Hazarika, 2020).

The Role of the State in the Redevelopment of Informal Settlements

It is now known globally, especially in cities of the global south, that instead of the redevelopment of informal settlements, upgradation of existing housing is the more efficient solution apart from being the cheapest, most direct and quickest way to improve housing for residents in informal settlements (Bhan et.al. 2020). However, in the case of Delhi, the state continues to push for redevelopment of informal settlements that opens up state land for private investment and profit at the cost of potentially uprooting millions of lives.

Examining the role of the state in choosing redevelopment over upgradation reveals that it is a choice that is political in nature. Apart from incentivizing private capital and investment into state lands, the postcolonial state in Delhi also chases ‘aesthetic’ (Ghertner, 2011) ideals through urban redevelopment which is evident from the emphasis on building ‘high-rise’ apartments that fit a certain ‘world-class’ city image. The question remains: at what cost?

As Gupta (2019, p.1126) writes, “’Capital’ does not just ‘find’ its way to places, it is directed and guided, and enabled to take hold. In short, it is governed. The consequences of this governance are significant: it determines who exercises power to make claims on the city and its allocations of spaces. Which uses of land have been prioritised and justified, and populations exercise agency in the city…”. The role of the state in pushing for redevelopment projects of a certain kind involving and attracting private capital in the city of Delhi especially when the viability of these projects is questionable on multiple grounds highlight the skewed priorities of urban governance and welfare. It becomes important, therefore, to ask and probe as to whose interests are being catered to in the process of urban redevelopment in Indian cities?

Final remarks

In Delhi, thick in the middle of a global pandemic, a wall was erected dividing the informal settlement of Kusumpur Pahari on one side and the surrounding residential enclave on the other “to prevent the spread of COVID-19 from the slum” to the surrounding more affluent neighborhood (The New Indian Express, 2020). The residents of Kusumpur Pahari wrote to the municipal officials complaining about the illegal residential segregation but to no avail. Therefore, we see that discursive public narratives of ‘squalor’ and ‘filth’ continue to be associated with ‘slums’ or informal settlements in Delhi regardless of the actual quality of housing in these spaces, while the state prioritizes private profit over the same parcel of land under the grab of ‘redevelopment’. In this context, it becomes increasingly important to identify the specific interests that drive policies such as ISSR 2019. It is paramount also to understand who stands to benefit from the increasingly financialised urban transformation that is taking place through real estate frontiers in cities of the global south today and at what cost.

References

Bhan. G., Shakeel, A. Kumar, N. Chakraborty, I. Joshi, S. and Yadav, M. (2020). Isn’t there enough Land? Spatial Assessments of ‘Slums’ in Delhi. Indian Institute of Human Settlements, Bangalore, India.

Bhide, A. (2015). City produced: urban development, violence, and spatial justice in Mumbai. Centre for Urban Policy and Governance, School of Habitat Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai

Delhi Development Authority (2019). Policy for In-Situ Slum Redevelopment /Rehabilitation by the DDA. New Delhi.

Delhi Development Authority (2020). Minutes of the meeting held on 16.01.2020 at 11.00AM with Real Estate Developers to apprise them regarding upcoming In-Situ Rehabilitation/Redevelopment Projects of DDA on ‘PPP’ mode.

Ghertner, D.A. (2011). Rule by aesthetics: World-class city making in Delhi. Worlding cities: Asian experiments and the art of being global, 279-306.

Ghertner, D.A. (2014). India’s urban revolution: geographies of displacement beyond gentrification. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 46.7, 1554–71

Gillespie, T. (2020). The Real Estate Frontier. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 44(4), 599-616.

Gupta, P. S. (2019). The entwined futures of financialisation and cities. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 43(4), 1123-1148.

Hazarika, N. (2020). Spaces of Intermediation and Political Participation: A Study of Kusumpur Pahadi Redevelopment Project 2019. IFI-CSH Working Paper #16, New Delhi.

Mahadevia, D. (2006). NURM and the poor in globalising mega cities. Economic and Political Weekly, 3399-3403.

Mahadevia, D., Bhatia, N., & Bhatt, B. (2018). Private Sector in Affordable Housing? Case of Slum Rehabilitation Scheme in Ahmedabad, India. Environment and Urbanization ASIA, 9(1), 117.

Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation (2015). Pradhan Mantru Awas Yojana ‘Housing for All (Urban) Scheme Guidelines’, Government of India, New Delhi.

Mukhija, V. (2001). Enabling slum redevelopment in Mumbai: Policy paradox in practice. Housing Studies, 16(6), 791–806.

Mukhija, V. (2003). Squatters as developers: slum redevelopment in Mumbai. Ashgate, Burlington, VT.

Moore, J.W. (2000). Sugar and the expansion of the early modern world-economy: commodity frontiers, ecological transformation, and industrialization. Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 23.3, 409–33.

Moore, J.W. (2015). Capitalism in the web of life: ecology and the accumulation of capital. Verso, London.

Parnell, S. and J. Robinson (2012). (Re) theorizing cities from the global South: looking beyond neoliberalism. Urban Geography 33.4, 593–617.

Roy, A. (2005). Urban informality: toward an epistemology of planning. Journal of the American Planning Association 71.2, 147–58.

Roy, A. (2009). The 21st-century metropolis: new geographies of theory. Regional Studies: The Journal of the Regional Studies Association 43.6, 819–30.

Roy, A. (2016). Who’s afraid of postcolonial theory? International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 40.1, 200–9.

Schindler, S. (2017). Towards a paradigm of Southern urbanism. City, 21(1), 47-64.

Schindler, S. and J.M. Kanai (2018). Producing local commodity frontiers after the end of Cheap Nature: an analysis of eco-scalar carbon fixes and their consequences. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 42.5, 828–44.

Smith, N. (1996). The new urban frontier: gentrification and the revanchist city. Routledge, Abingdon.

The New Indian Express (2020). ‘Slum residents fume over wall construction after COVID-19 cases in Delhi’s Vasant Vihar’.

About the author

Naomi Hazarika is a doctoral student at the National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration, New Delhi and holds a Master’s degree in Political Science from the Center for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India. Her research is on the intersection of the political economy of urban development and the relationship between state, capital and citizens in the city of Delhi, India.