Challenges and opportunities of slow tourism for rural development and sustainability

DOI reference: 10.1080/13673882.2021.00001099

By Sarah Diefenbach, Master Student of the Master in Sustainability, Society and the Environment at Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, Germany

Introduction

Up until the outbreak of the Covid-19 global pandemic, the tourism sector and mass tourism have seen constant growth, enabled by rising prosperity in developed economies, advances in transportation technology, availability of oil, and consumer demand by a wealthy middle class. However, researchers have repeatedly called out that, due to its impact on the environment and local people, mass tourism is not sustainable in the long run (Fullagar et al. 2012), and the World Tourism Organisation has acknowledged this by making sustainability a priority (Oriade & Evans, 2011).

Parallel to the rising concerns about the future of tourism, the Slow Tourism (ST) movement developed. It counteracts the prevailing trend to travel further, faster and more often, encouraging an increased consciousness of tourism’s impact on social, cultural and environmental aspects (Fullagar et al. 2012). Perhaps the first author to argue for a slow approach to tourism within an academic context was Rafael Matos-Wasem, an economic geographer. According to Rafael Matos-Wasem, the essence of ST is to take time and to attach to the place at the destination (Fullagar et al. 2012). In consequence, the ST movement is believed to have a positive impact on the social and economic environment at the destination (Serdane et al. 2020).

This article will explore whether Slow Tourism can serve as an effective sustainable alternative to current forms of tourism and how it can support rural development.

Tourism and Rural Economic Development

The tourism sector accounts for 7% of worldwide exports, one in eleven jobs, and 10% of the world’s GDP (World Tourism Organization or UNWTO, 2017). If it is well managed the tourism sector can promote economic growth, social inclusiveness, and the protection of cultural and natural assets (UNWTO, 2017). This idea is referred to as tourism development and means the “encouragement of soundly based tourism initiatives, with policy, planning and implementation”, that would make less developed regions viable members of the international economy (Robinson et al. 2011, p. 16).

In rural areas, tourism can promote economic development through a variety of aspects. For example, since the rise of accommodation booking platforms like Airbnb or activity offering platforms like Tripadvisor, it has become easier for locals and small businesses to reach potential tourists (Bosak & McCool, 2019), which can lead to a redistribution of income from wealthier cities towards the countryside (Manuel-Navarrete, 2016). Furthermore, tourism development is often accompanied by beneficial improvements in the local infrastructure (Dieke, 2011). As ever-growing economic sector tourism is constantly developing new niches and presents an opportunity for regions, where skills, resources, or technologies to drive manufacturing or other sectors are in short supply (Aoyama et al. 2011).

Despite these potential benefits, there is a risk that tourism development will lead to more foreign ownership in the area, thus to a leakage of economic benefits (Robinson et al. 2011), to political dependency (Schmallegger et al. 2010), as well as to rising costs of living for residents (Dickinson & Lumsdon, 2010). Lastly, an overreliance on the sector can lead to economic shocks, if tourists suddenly stop arriving (De Bellaigue, 2020), recently proven by the global pandemic.

Sustainable Tourism and Slow Tourism

Sustainable tourism emerged roughly 25 years ago in the context of global concern about the environment, and as a response to mass tourism and its negative impacts (Bosak & McCool, 2019). The UN World Tourism Organisation defines sustainable tourism as “tourism that takes full account of its current and future economic, social and environmental impacts, addressing the needs of visitors, the industry, the environment, and host communities” (European Travel Commission, 2019, p. 11). The often negative environmental and economic impacts associated with mass tourism (Bosak & McCool, 2019), changes in customer demand, and a rising concern for the environment have led to the tourism sector’s search for more sustainable alternatives (Robaina & Madaleno, 2019). This resulted in expressions like green tourism, eco-tourism, alternative tourism, pro-poor tourism, and Slow Tourism. The latter will be introduced in more detail in the next part.

The concept of slowness originated in the slow food and slow cities movement in Italy, encouraging “fewer but more high-quality experiences that respect local cultures, history, environment and social responsibility, […] [and] a connection between tourists and host communities” (Heitmann et al. 2011, p. 117). As well as a fast pace of travel, ST discourages fast food and mass consumption. Additionally, it is often related to ecology and sustainable development by focusing on local production and environmental protection (Dickinson & Lumsdon, 2010). As such, ST is not only concerned with the mode and speed of transport, but also with the impact it has on the attitudes of Slow Tourists, and the natural and social environment, including the impact on residents and tourism operators.

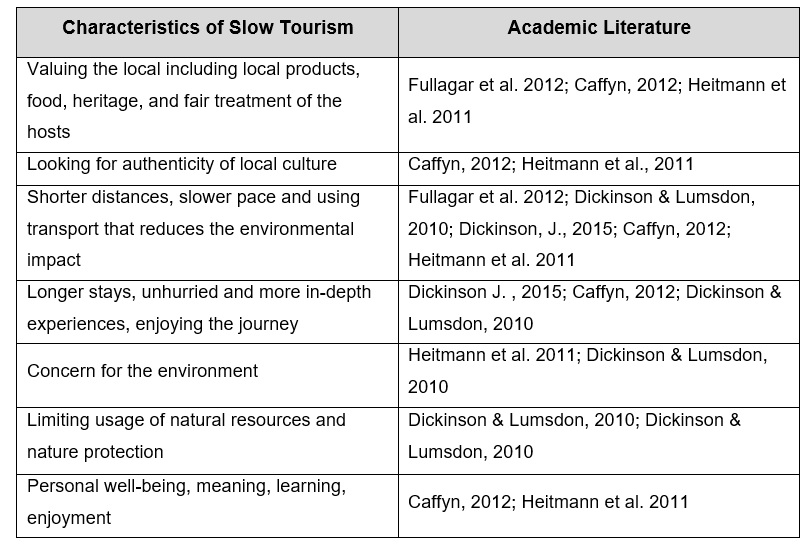

The following Table 1 provides a summary of the key characteristics of ST, which are repeatedly mentioned in academic literature.

Table 1: Common characteristics of Slow Tourism in academic literature.

An Example in Practice: Slow Tourism in Latvia

In Latvia, Slow Tourism was chosen as Latvia’s national tourism brand, called Latvia – Best Enjoyed Slowly, which was in place from 2010 until 2015. Slow Tourism was understood to invite the country’s visitors to slow down in pace, to stop and enjoy unhurried leisure, and to think about values and the important issues of life. For Latvia, the main goal was to promote the country as a sustainable tourism destination, targeting the following three objectives: Increasing the length of stays, increasing the tourism sector’s share of GDP, and lastly promoting the development of local and regional tourism products. The implementation of the national brand was accompanied by a marketing campaign, additional personnel, and funding of five million Euros. As a result of implementing the Slow Tourism slogan and the marketing campaign, Latvia has achieved an increase of 75% in tourism numbers between 2010 and 2016, has introduced high quality and sustainable tourism products, and has created an image of a tourism destination with rich culture and pure nature (Luka, 2017).

In 2017, Dr. Zanda Serdane performed 37 in-depth interviews with both local and foreign tourists as well as tourism providers. Below the key findings from those interviews, that are related to economic development and sustainability, are summarised.

The interviews revealed that most people involved with Slow Tourism do not have an increased eco-consciousness or concern for the environment (Serdane et al. 2020), nevertheless, many respondents stated that they related Slow Tourism to being in a pleasant environment and to rural, non-urban environments and nature (Serdane, 2017). In terms of modes of transport, the study showed that tourists mostly chose based on convenience and availability, meaning that both fast and slow modes of transport were used (for fast travel, locals most often used cars and foreign tourists used planes, buses, trains, or cars) (Serdane et al. 2020). Many respondents associated Slow Tourism with travelling shorter distances and staying at one place for a longer time to deeply experience people, places, and cultures (Serdane et al. 2020). The interaction with hosts and the support of smaller local businesses was recognized as a key factor for Slow Tourism, also resulting in fairer prices for the supply side (Serdane et al. 2020).

Regarding the economic development potential, the interviews revealed a controversy about the economic viability of Slow Tourism, mainly because it is rather small-scale and loses its character when the scale increases. That is why Slow Tourism is often offered as a side business in Latvia, by providers who see it as a hobby rather than their main job (Serdane, 2017). This is also underlined by some respondents who suspected that due to the slow travel pace (often in nature), tourists might consume less and spend less, whereas others see a potential for more spending due to the longer stays in one place (Serdane, 2017).

Discussion and concluding remarks

Opportunities of the Slow Tourism movement for rural economic development include the consumption of local food and products, accompanied by an increased willingness to pay a fair price for accommodation or services (Fullagar et al. 2012), preservation of traditional ways of production and cultural heritage, the attraction of wealthier tourists resulting in higher spending (Luka, 2017; Heitmann et al. 2011), a different distribution of income by moving money to smaller, often family-run businesses (Murayama & Parker, 2012) and improved infrastructure, including public transport and National Parks (Farrell & Russell, 2011). Furthermore, it can be said that ST is characterised by a connection with local hosts and the environment. Through an in-depth experience of local day-to-day life, (urban) Slow Tourists might also gain a better understanding of rural life, remove preconceptions, and even consider moving to the countryside themselves. Consequently, ST could become a way to attract more residents to rural areas (Murayama & Parker, 2012), who could also bring job opportunities outside of the tourism sector with them.

Even though environmental concerns have been identified as a major driver of ST, the Case Study in Latvia showed that tourists or tourism providers only rarely relate ST with protecting the environment. Especially, a change of transport towards less resource-intensive modes proves less common in practice, as often Slow Tourists continue travelling by air to arrive at their main travel destination. The issue of excluding the aviation industry from policies towards more sustainable tourism practices has been called out by several academics (Fullagar et al. 2012; Dickinson J., 2015; Hall et al. 2015). Additionally, like with other forms of tourism activity, ST should be developed carefully and in a coordinated way, as expanding it rapidly might lead to adverse impacts on the environment or society (for example, through land-use conflicts, changes in the appearance of rural areas, the rising cost of living, etc.) (Oriade & Evans, 2011; Dodds, 2012). Especially, in rural areas reliant on agriculture ST could lead to a conflict over water, energy, or human resources, risking the loss of traditional practices and jobs in the area.

Based on the reviewed literature and case study in Latvia, it can be said that ST could play an important role in economically developing rural destinations. Due to ST’s focus on experiencing the local and valuing tradition and the host culture, ST could help overcome some of the major challenges in economic development through tourism, namely economic leakages, increased cost of living and overreliance on tourism. A precondition for this would be, that the ST concept is developed carefully and well managed, preventing over-tourism, loss of local heritage, and unequal distribution of income.

For a successful implementation of Slow Tourism (ST) and to fully assess its potential as a more sustainable way of tourism, several research questions remain: How can ST be implemented and scaled up in a sustainable manner? Can ST push the tourism sector towards the use of more sustainable modes of transport? Which policy changes and infrastructure development would be required to move the tourism sector away from aviation as the most convenient mode of transport?

References

Aoyama, Y., Murphy, J., & Hanson, S. (2011). Key Concepts in Economic Geography. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Bosak, K., & McCool, S. (2019). Tourism and Sustainability: Transforming Global Value Chains to Networks. In M. e. Schmidt, Sustainable Global Value Chains (pp. 585-595). Montana, USA: Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

Caffyn, A. (2012). Advocating and Implementing Slow Tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 77-80.

De Bellaigue, C. (2020). The end of tourism?

Dickinson, & Lumsdon. (2010). Slow Travel and Tourism. London: Earthscan.

Dickinson, J. (2015). Slow travel. In C. M. Hall, S. Goessling, & D. Scott, The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability (pp. 481-489). London/New York: Routledge.

Dieke, P. (2011). Aspects of Tourism Development. In P. Robinson, S. Heitmann, & P. Dieke, Research Themes for Tourism (pp. 16-30). Wolverhampton/Fairfax: CAB International.

Dodds, R. (2012). Questioning Slow As Sustainable. Tourism Recreation Research, 37(1): 81-83.

European Travel Commission. (2019). Report on European Sustainability Schemes and their Role in Promoting Sustainability and Competitiveness in European Tourism. Brussels: European Travel Commission.

Farrell, H., & Russell, S. (2011). Rural Tourism. In P. Robinson, S. Heitmann, & P. Dieke, Research Themes for Tourism (pp. 100-113). Wolverhampton/Fairfax: CAB International.

Fullagar, Markwell, & Wilson. (2012). Reflecting Upon Slow Travel and Tourism Experiences. In S. Fullagar, K. Markwell, & E. Wilson, Slow Tourism – Experiences and Mobilities (pp. 227-233). Bristol: Cooper, C.; Hall, C.M.; Timothy, D. Aspects of Tourism: 54.

Hall, C., Goessling, S., & Scott, D. (2015). Tourism and Sustainability – Towards a green(er) tourism economy? In C. M. Hall, S. Goessling, & D. Scott, The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability (pp. 490-519). London/New York: Routledge.

Heitmann, S., Robinson, P., & Povey, G. (2011). Slow Food, Slow Cities and Slow Tourism. In P. Robinson, S. Heitmann, & P. Dieke, Research Themes for Tourism (pp. 114-127). Wolverhampton/Fairfax: CAB International.

Luka, M. (2017). Brand Tour – Building Latvian Tourism Identity.

Manuel-Navarrete, D. (2016). Tourism and Sustainability. In H. e. Heinrichs, Sustainability Science (pp. 283-291). Tempe, USA: Heinrichs, H. et al. (eds), Sustainability Science.

Murayama, M., & Parker, G. (2012). Fast Japan, Slow Japan: Shifting to Slow Tourism as a Rural Regeneration Tool in Japan. In S. Fullagar, K. Markwell, & E. Wilson, Slow Tourism – Experiences and Mobilities (pp. 170-184). Bristol: Channel View Publications.

Oriade, A., & Evans, M. (2011). Sustainable and Alternative Tourism. In P. Robinson, S. Heitmann, & P. Dieke, Research Themes for Tourism (pp. 69-86). Wolverhamption/Fairfax: CAB International.

Robaina, M., & Madaleno, M. (2019). Resources: Eco-efficiency, Sustainability and Innovation in Tourism. In E. Fayos-Sola, & C. Cooper, The Future of Tourism – Innovation and Sustainability (pp. 19-41). Madrid and Leeds: Springer International Publishing AG.

Robinson, P., Heitmann, S., & Dieke, P. (2011). Research Themes For Tourism. Oxfordshire.

Schmallegger, D., Carson, D., & Tremplay, P. (2010). The Economic Geography of Remote Tourism: The Problem of Connection Seeking. Tourism Analysis, 15(1): 127-139.

Serdane, Maccarone-Eaglen, & Sharifi. (2020). Conceptualising slow tourism: a perspective from Latvia. Tourism Recreation Research, 45(3): 337-350.

Serdane, Z. (2017). Slow Tourism in Slow Countries: The case of Latvia. Salford: Salford Business School.

World Tourism Organization=UNWTO (2017). 2017 IS THE INTERNATIONAL YEAR OF SUSTAINABLE TOURISM FOR DEVELOPMENT.