Romania’s accelerated digitalization in pandemic times: The (dis)trust-(anti)corruption nexus

DOI reference: 10.1080/13673882.2021.00001098

By Adriana Mihaela Soaita, Research Fellow at the University of Glasgow, UK.

The Covid-19 public health emergency has amplified corruption globally not least across the pharmaceutical industry, within governments’ ‘VIP lanes’ for Covid-19 suppliers, and further down to individuals’ access to vaccination, tests and healthcare (Mucchielli 2020; Teremetskyi et al. 2021). To corruption, Romania is neither an exception nor a newcomer. However, while levels of corruption might have increased in the short term in Romania, Adriana Mihaela Soaita argues that the accelerated institutional digitalization prompted by the pandemic will restrain corruption in the longer term. Her argument draws on a longitudinal-qualitative case study, which finds e-governance to be a socially trusted anticorruption mechanism, besides being a welcomed institutional reform.

Introduction

It is striking that a great majority of Europeans believe corruption is widespread in their countries (i.e. “happening in many places and/or among many people”, Cambridge Dictionary), yet few have experienced it. In the least corrupt European Union (EU) member states of Denmark, Finland, and Sweden, between 20% and 44% of people thought corruption was widespread; in Slovenia and Italy, over 90% believed the same, but fewer than 3% in all the aforementioned countries actually indicated they had paid or were expected to pay a bribe in the last year (EC 2014, data from 2013). In Romania, the respective figures are 93% (for belief) and 25% (for experience). The difference between perceptions and experiences is puzzling and indicates that people’s meanings of corruption should be better understood.

Designing anticorruption policies that are trusted by citizens has possibly never been more important given increasing EU fiscal integration and the €1.8 trillion post-COVID stimulus package. Moreover, the EU has engaged in fighting corruption above and across its member states, having opened the European Public Prosecutor’s Office in September 2020, led by the Romanian prosecutor Laura Codruța Kövesi. Within the EU, the post-communist states show higher than average levels of corruption, commonly seen as a lingering communist legacy and/or defective institutionalization (Mungiu-Pippidi 2005; Rose 2009), although some countries, particularly Estonia, have achieved spectacular progress in controlling corruption, including through an advanced e-governance regime (Kasemets 2012).

Post-communist Romania took a slower and twisting path. Since 2012, a remarkable high-level anticorruption drive has taken place, with Kövesi at its center. Over 2,000 high-ranking public executives have been convicted, including one Prime Minister, 21 Members of Parliament (MPs) and 30 judges; but misappropriated funds have been rarely recovered. Recent parliamentary attacks on the independence of the judiciary were fought through street protests, leading to the 2019 ‘Justice’ referendum, which showed Romanians endorse the fight against corruption. There are, however, limits to such a judiciary approach. If fully applied, in any one year about a quarter of Romanians (in similar numbers to Poles and Hungarians) would be jailed for giving and most medical stuff for receiving (Manea 2014) a medical bribe, with national health services collapsing due to a lack of staff. Other notable measures to constrain corruption in Romania included raising public pay and public awareness. Overall, Romania’s judiciary and anticorruption performance is still monitored through the EU Cooperation and Verification Mechanism, showing that progress has been partial.

Given EU’s and Romania’s anticorruption agenda, the Regional Studies Association gave me the opportunity to explore the (dis)trust¾(anti)corruption nexus through a qualitative-longitudinal study by revisiting the Romanian city of Pitesti (Figure 1), where I had first examined these themes in 2008.

While analysis of the rich data collected is ongoing, in this article I wish to posit digitalization as a socially trusted anti-corruption mechanism. Finding socially trusted mechanisms to address social ills or dilemmas is important, particularly in a context of distrust in the institutions that oversee the rule of law and administrative impartiality.

Mapping the (dis)trust-(anti)corruption nexus

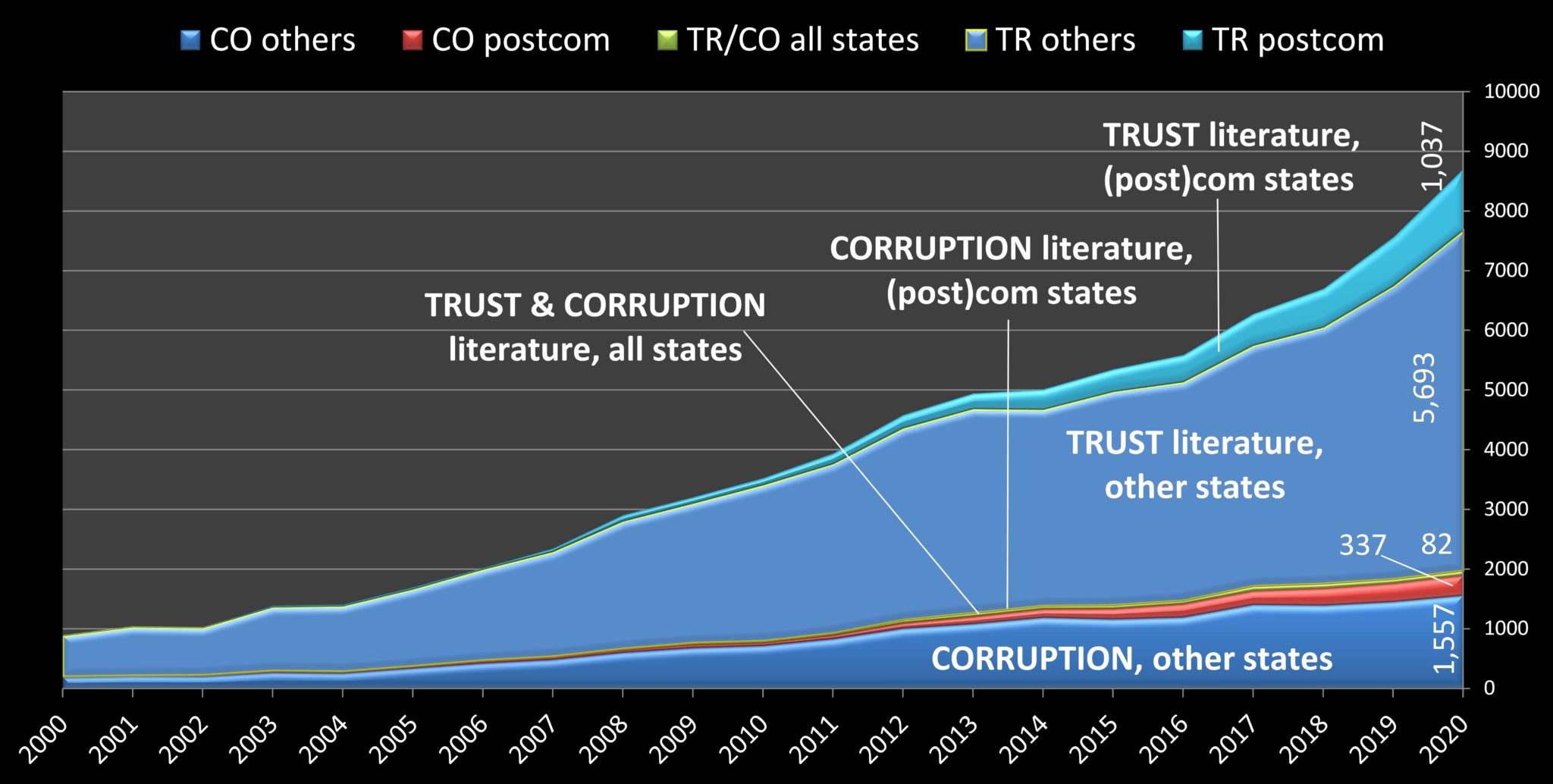

The academic literature about trust looms so largely (Figure 2) that we need a theoretically refined synthesis against which to position empirical work. The literature delves into detailed rational-choice accounts and game theory, and at times into finely-grained analyses of relational practices, inspiring historical analyses or philosophical work. Trust is understood as, some or all of, historic culture, institutions, norms, rational practices, and personal leaps of faith. This scholarship validates our intuitions that inscribed, institutional or social trust is hard to win, easy to lose, develops along continua (from complete distrust to blind trust, but mostly in between), is never a zero-sum game, and is differently distributed across societies and social groups. There is general agreement that social and institutional trust facilitates better economic performance, healthier democracy, and higher citizens’ wellbeing. Most post-communist countries still show low levels of trust and higher levels of distrust than established democracies (Soaita and Wind, 2021). In 2011, Romania showed one of the lowest levels of trust globally.

Figure 2. Mapping the trust and corruption ‘literature’ (yearly no. of publications, shown from 2000)

Searched in SCOPUS on 19 May 2021 in titles, abstracts, and keywords for the words: Trust (TR): 68,343 publications; timeline 1889-2021; of these, 15% are qualitative studies. Corruption (CO): 20,737 publications; timeline 1892-2021; of these, 9% are qualitative studies. Results restricted to articles, books and book chapters and to the disciplines of Arts and Humanities; Business, Management and Accounting; Economics; Psychology; Social Sciences. Source: the author.

The corruption scholarship is about two-thirds smaller than works on trust. It glides through narrow, legal definitions and occasionally through broader, nuanced understandings of what we deem to be (un)ethical across the domains of the economic, the cultural and the political (Ackerman and Palifka 2016). Analyses centre on the public domain, often calling for the ‘small state,’ notwithstanding the fact that controlling corruption requires public and private institutions (e.g., an independent judiciary, media, NGOs), and that corruption independently occurs in the private domain (Burduja and Zaharia 2019). The big difference between perceptions and

experiences of corruption remains poorly explained, its complex foundations (between the legal and the ethical, the factual and the perceptual, the trusted and the distrusted, the citizenry and the elite) being overlooked (except e.g., Rose-Ackerman and Palifka 2016). Various practices of corruption (e.g., nepotism, favouritism, cronyism, personal connections, gift, bribery, sextortion, undue influence, extortion, fraud, kickbacks) are summoned into one definition, e.g., “abuse of entrusted power for private gains” (transparencyinternational.org). Some forms of corruption could be thought of as social dilemmas: if every contractor or patient would stop paying a kickback or a medical bribe, all businesses and patients would be better off (but public remunerations may need to increase).

Surprisingly, trust and corruption analyses barely explicitly overlap. The yellow line in Figure 2 is hardly visible (n=871, timeline 1990-2021; 10% qualitative studies; 4 publications on Romania). The geopolitical area of (post)communism is under-represented (8% and 12% for trust and corruption respectively) but has grown since 2010, and empirically qualitative accounts are rare. These observations show that exploring the (dis)trust-(anti)corruption nexus through a rich longitudinal-qualitative study sits within important literature gaps.

The data

The Covid-19 pandemic disrupted my planned fieldwork, accommodation and flights having been already booked. Nonetheless, with the help of a local assistant and remote interviewing, I achieved my desired longitudinal sample and interviewed 16 participants out of the 69 who participated in my early research back in 2008 (aged 48-85 in 2020). This was enhanced with a small subset of eight younger, new participants (aged 23-38; recruited through the Facebook group ‘Pitesti, orasul meu’). Recorded ZOOM interviews were conducted during May-Sep 2020; they were unusually long, lasting on average two hours (the longest four hours and a half). The interview focused on trust (e.g., trusted/distrusted institutions/persons; social and institutional trust; trends), corruption (gifts vs bribes; tax evasion vs corruption; nepotism/favouritism; top-corruption; trends); and anticorruption measures, with participant examples discussed first, followed by researcher structured probes.

Legality and morality in the corruption repertoire

The fact that participants discussed many but barely any COVID-related examples is telling rather than surprising. It tells that Romania is far from the newcomer to corruption stories and perhaps also that “saving lives justifies speed beyond and above the worry for corruption” (r19/male/aged-48). Indeed, 53% of Romanians believed in 2020 that “it is acceptable for the government to engage in a bit of corruption as long as it gets things done and delivers good results” (TI 2021). Some participants in my study believed the same but many were aghast by this way of thinking:

I often heard people saying, “He did steal, but he got things done, right?” I pay attention to people’s reactions when it comes to corruption, and everyone reacts alike, which means it’s a collective mindset. Or, in a slightly different form, as one shocked me by asking me “if YOU had the jar of honey in front of you, wouldn’t you lick your fingers?” Yes, that is the sad mentality at the moment. People actually legitimize theft because the culprit had delivered something, had not stolen everything. Or because, even when convicted by Court, they remain with the stolen money (r13/male/aged-38).

Participants’ examples of practices of corruption were those from their everyday lives, such as medical bribes; a badly constructed bridge, road or school; the ‘good-and-bad detective’ plot played by (fiscal, police, health) agents of control; jobs accessed through ‘nepotism’ or enormous bribes (priests, surgeons, lawyers, managers in multinationals, drivers). Other examples were brought home by the media, referring to many convicted names or dealings of public resonance. Corruption is so ubiquitous in the public discourse and its emotional load so intense, that some participants preferred to take a step away for their own sanity:

I watch very little news, but I get informed from discussions with mom and colleagues. But I, personally, I am not very interested in these things. I don’t know if it’s necessarily a good way to be disinterested, but it makes me so nervous because I hear nothing but nasty things, only corruption, what this one did, what that one did. It is just makes me so angry hearing about those deals (r10/male/aged-35).

By discussing the above and other examples, it became clear there were fluid tensions between legal and ethical understandings of corruption. On the one hand, laws were presented as being (re)made by a highly untrusted political class, to their own advantage. Indeed, in 2021 Romania showed the lowest level of trust in the government (20% of the population) and the highest share of people believing that the Parliament, national government, and the Prime Minister are all corrupt, i.e.: 51%, 40% and 37% of people, respectively, almost twice the EU average (TI 2021).

On the other hand, the moral repertoire of corruption, as conferred by participants, looms large from givers’ pragmatism, despondency or gratitude, to takers’ sense of deservingness, greed or shamelessness, and further to win-win, supply-demand arrangements. For instance, “Maria” (r20/female/aged-25) purposefully argued for the legal understanding of corruption as ”taking a personal advantage of a privately or publicly position by illegal means”. However she and other young participants decried widespread practices of ‘nepotism’/‘favouritism’/’personal connections’ in accessing the public/private labour market against which no legal framework exists (except for few positions necessitating open competition, themselves abused).

Likewise, most participants considered that small ‘gifts’/’attentions’ are socially acceptable despite legal prescriptions criminalizing givers and receivers irrespective of the value of the bribe. Participants emphasized that offering a gift (when they want and not necessarily in exchange for an immediate service) is socially accepted for personalizing the relationship, equalizing the balance of power, expressing one’s social position or just because ”we are kind people” (quote across interviews). The interview question on what makes the difference between a gift and a bribe showed that boundaries are hard to define (value, timing, and sentiment) and depend on one’s subjectivity and socioeconomic position.

Interestingly, with the exception of a few participants owning small businesses, most others saw no difference between corruption and tax evasion/avoidance since both are ”thefts of public money” (quote across interviews), paid or dodged. They are also interlinked. There was vivid preoccupation regarding which one was more ‘immoral’, or whom should make the first move towards a less corrupt society. This ‘chicken versus egg” argument frames many social dilemmas and, I argue, it should be deconstructed by anti-corruption policies that equally and concomitantly tackle both. Similarly, certain forms of fraud e.g., industry ‘market’ practices, revolving doors (the public/private health system), a bonus culture (including special pensions for the political/judiciary elite) and inequality in front of the law entered the corruption discourse. Rothstein’s (2011) argument that we mobilise different moral rules across different social domains (family, market, public institutions) did not neatly apply, e.g., market greed was sanctioned as corruption rather than approved, reflecting a society that has experienced ”the wild capitalism of transition” (r10/male/aged-35).

I would like to emphasize that, at times with evident distress, participants resented the fact that Romania is stigmatized internationally as a corruption hot spot:

Everyone asks us about corruption, but corruption was invented by those ‘clever’ boys of Germany, France, England, by them. I suggest you ask them, in England, see what do they say? They are ‘clever’ boys, they made corruption legal for them, and made ‘criteria’ for us, want us to have ‘transparency’. Do they have transparency in England? They steal billions of pounds in legal corruption, and we are singled out for stealing millions of lei. This hypocrisy makes me very angry (r19/male/aged-48).

Recent opinion data (TI 2021) seem to support this view in terms of tax avoidance and governments being run by private interests, explaining some of the puzzles of the big differences between perceptions and experiences of corruption. As I have lived in the UK for some time, I have indeed noticed that Romanians’ predilection to class a whole range of social practices as corruption is equally matched by a British reticence of applying the concept to any of their own.

Fighting corruption

Understanding how such cultural/structural, legal/moral complexities play out in the flamboyant corruption’s public/private repertoire is important in order to understand how corruption can be fought in a socially acceptable way. No participant contested the legitimacy of fighting corruption as ”you change chaos into normality” (r11/female/aged-52); ”we will all be richer, materially and emotionally, we would be unsoiled, not anymore scared by our own shadow” (r17/female/aged-85); ”there would be trust between the doctor and the patient, the citizen and the administration” (r2/male/aged-59). However, given corruption’s recognized normalization and in-built social dilemmas, not many participants believed it could ever be eliminated; at best reduced by ”building a self-cleaning system” (r13/male/aged-38).

All participants endorsed the judicial approach, undaunted by narratives of the whole (health) service collapsing as a result and that was because they believed in its preventative power, if applied fully (recovering misappropriated funds; firmer sentences) and in a non-politicized manner. Criticism, of which there was plenty, was not against but for a stronger judiciary approach, for which some participants had taken to the streets in 2018. Participants mentioned other ways of reducing corruption, such as civic education (n=6), marketization (n=2), the ‘small state’ (n=1) and professionalization (n=1), before being prompted to discuss the efficacy of my own suggestions, some inspired from the corruption literature, others from policy developments in Romania. The former included pay rises, institutional digitalization, transparent procurement and the judiciary approach (see e.g. Manea, 2004; Mungiu-Pippidi 2005; Rothstein 2011), the latter referred to CCTV, anticorruption posters and street protest.

Commonly, participants were surprised by casting digitalization as an anti-corruption strategy (except two who discussed it unprompted) while wholeheartedly admitting its potential:

I never thought of digitalization from this perspective, but just as a timely administrative reform. But digitalization reduces human contact, hence the possibilities to demand or offer bribes, it is just you and a robot, it leaves a hard trail behind (r20/female/aged-25).

The Covid-19 accelerated digitalization was observed and approved:

Public institutions should develop digital platforms and the truth is the pandemic has super-accelerated it. Education moved online, teachers and children and parents had to learn it. The Pension Department moved online, the Court moved online, prescriptions moved online. If you digitalize, there are no longer opportunities to bribe, to cook the book. You fill in a form, say what you want, attach documents, it’s there, can’t be changed, it’s transparent (r2/male/aged-60).

Trust in digitalization and other ICT technologies (CCTV, bank cards) as anticorruption mechanisms was high but not blind. Three participants saw digitalization as effective in reducing small but not necessarily top-level corruption, with the latter becoming more imaginative and sophisticated (a shared view among participants). One thought that effects needed time to filter down whilst digitalization progresses; another observed the important need to monitor the digital space (a ‘second-order’ dilemma in managing trust and corruption).

While I asked about institutional digitalization, participants also brought to the fore the anti-corruption potential of the technological/digital society:

Technology has changed everything; people in their 60s, elderly in their 70s, walk-and-talk on their mobiles, watching Facebook when crossing the street (r14/male/aged-49).

The Internet changed everything. People now film and their videos become viral. I saw many cases, people filming how doctors demand bribes, how horribly they were treated. And it matters as those feel shamed or scared to lose their job (r23/female/aged-29).

The issue of digital exclusion remains pertinent¾ more so in rural places and for certain social categories¾despite intergenerational mediation, even transnationally, as also substantiated by Iossifova (2020) for the case of Bulgaria’s elderly:

Ha, ha we had to submit the paperwork to the Town Hall, for this new system of billing; by electronic post or by internet or what-you-call-it, and it was my daughter from Luxembourg who did it for me: Luxembourg-Pitesti, ha, ha (r17/female/aged-85)

My fieldwork took place before the implementation of the Covid-19 vaccination programme (led by the most trusted Romanian institution, the Army), including through a national digital platform. Prioritized, the elderly could arrange appointments by phone or through their Family Doctor, but there is anecdotal evidence not only that the family/social network stepped in to digitally make appointments but also that the digital platform was the preferred and more trusted option (later, with both increased vaccine supply and inoculation hesitancy, the platform lost its vital importance).

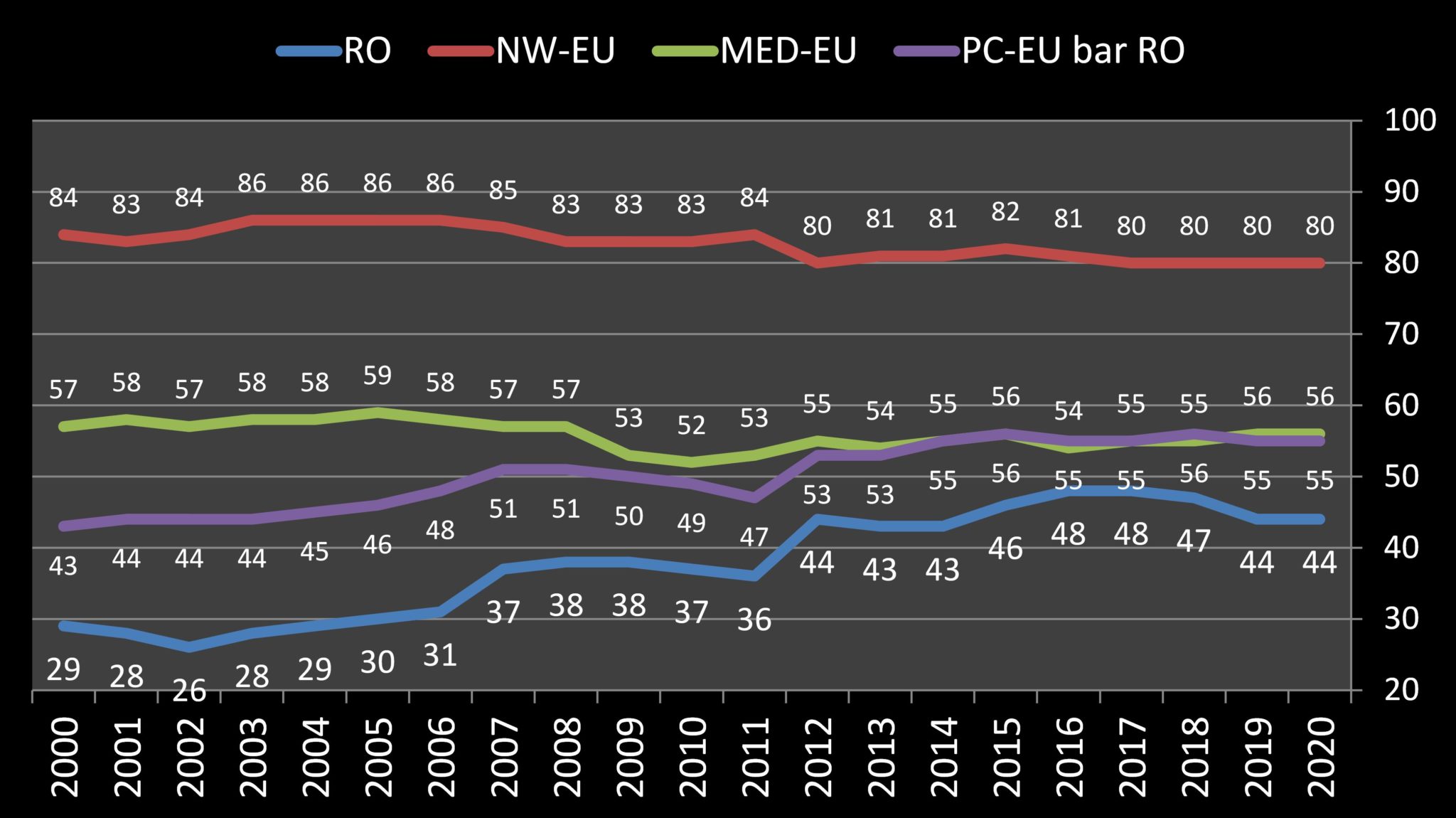

None of the anti-corruption methods discussed, from the symbolism of anticorruption posters to digitalization and further on to a firmer judiciary approach, were seen as a panacea by themselves, but most effective in combination. Participants used metaphors such as Hydra, octopus, Mafia, spider webs, blood spoiling the water, and the iceberg to describe the crisscrossing of diverse practices of small/top-level, private/public corruption. Nonetheless, even the most critical agreed that the situation had (slightly, barely) improved since 2008, particularly at the level of the everyday. Indeed, levels of experienced bribery fell from 25% to 20% over the decade to 2020. The public corruption index (Figure 3) shows significant improvement since 2000, with the EU post-communist countries closing the gap between them and the Mediterranean countries. Romania’s performance improved from values in the 20s in the first half of the 2000s, to values in the 30s in the second half of the same decade, farther on to values in the 40s in the 2010s. Nonetheless, Romania presented the poorest performance in the EU between 2000 and 2007, and shared the bottom four poorest performances after that (with Bulgaria, Greece, occasionally Italy and Hungary).

Figure 3. The public corruption index (transparency.org)

Source: By the author based on public data from https://transparency.org/en/ Highest values (max 100) show less(no) corruption.

A closing word on geography

In 2008, my participants cast geography (rural/urban and regional) and generations as axes of difference in relation to attitudes to and practices of trust, social capital and corruption, although World Values Survey data showed this was only partially true (Soaita and Wind 2021). By 2020, participants had stopped believing in generational differences, but geographical variation was still flagged:

In Pitesti things are changing for the better and this is the position I am talking from: I don’t live in a village to depend on the Mayor for wood, pension, taxes, I don’t know how people live there. I speak as a resident of a quite important and successful city (01/male/aged-41)

Things are different from city to city, from village to village, there are different models of cities, some with more trust and less corruption, others with less trust and more corruption. Trust and corruption can be very local matters (r3/female/aged-24)

The above reminds us that openness to digitalization must be seen as an urban phenomenon, villages being more likely places of digital exclusion. Furthermore, with other cities, including the capital of Bucharest, Pitesti has topped national news with large corruption scandals such as the fraudulent issuing of driving licenses at an international scale; a five-mandate Mayor sentenced to prison; a €400,000 public toilet. While more optimistic views may thus come from elsewhere, the hopeful trend taking place in such a corruption-stained city as Pitesti is even more telling of the positive changes occurring in Romania. Overall, with forthcoming EU funds being considered as corruption-proof, I agree with Neild (2002) that public outcry about corruption practices and scandals, as participants have so eloquently discussed, a signal that positive change is underway, even if only “because there is nothing left to steal” (r18/male/aged-50).

References

Burduja SI and Zaharia RM (2019) Romanian business leaders’ perceptions of business-to-business corruption: leading more responsible businesses? Sustainability, 11(20), 1-27.

EC (2014) Report from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament. EU anti-corruption report. Brussels: European Commission.

Iossifova D (2020) Translocal Ageing in the Global East: Bulgaria’s Abandoned Elderly, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-030-60823-1

Kasemets A (2012) The long transition to good governance: the case of Estonia. Paper presented at the XXII World Congress of International Political Science Association, July 8-12.

Manea T (2014) Medical bribery and the ethics of trust: the Romanian case. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 40(1), 26-43. doi: 10.1093/jmp/jhu049

Mucchielli L (2020) Behind the French controversy over the medical treatment of Covid-19: the role of the drug industry. Journal of Sociology, 56(4), 736-744. Mungiu-Pippidi A (2005) Deconstructing Balkan particularism: the ambiguous social capital of Southeastern Europe. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 5(1), 49-68. doi:

Neild R. (2002) Public Corruption: The Dark Side of Social Evolution. London: Anthem Press.

Rose-Ackerman S and Palifka BJ (2016). Corruption and Government: Causes, Consequences, and Reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139175098

Rose R (2009) Understanding Post-Communist Transformation: A Bottom Up Approach. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415482196

Rothstein B (2011) The Quality of Government: Corruption, Social Trust, and Inequality in International Perspective. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN: 9780226729572

Soaita AM and Wind B (2020) Urban narratives on the changing nature of social capital in post-communist Romania. Europe-Asia Studies, 72(4), 712-738. Teremetskyi V, Duliba Y, Kroitor V, Korchak N and Makarenko O (2021) Corruption and strengthening anti-corruption efforts in healthcare during the pandemic of Covid-19. Medico-Legal Journal, 89(1), 25-28.

TI=Transparency International (2021) Global Corruption Barometer European Union 2021. Citizens views and experiences of corruption. Transparency International.