By Ilaria Mariotti (e-mail), Associate Professor of Urban and Regional Economics, DAStU-Politecnico di Milano, Italy, Chair of the Cost Action CA18214, and Project Coordinator of CORAL ITN Marie Curie for the Politecnico di Milano.

This article was adapted and revised from the original “Mariotti I. (2021), Il lavoro a distanza svuota le città? Intervista a Philip McCann (Does remote working empty the city? An interview with Philip McCann), In Bellandi M., Nisticò R., Mariotti I. (eds.), Città e periferie alla prova del Covid-19: dinamiche territoriali, nuovi bisogni, politiche (Cities and peripheries to the test of Covid-19: territorial dynamics, new needs, policies), Donzelli Editore, Rome, pp. 25-35.

The Effects of the Covid-19 Pandemic on the City

The present paper explores the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the city by soliciting the reflections of an eminent urban and regional economics scholar, Philip McCann, to understand whether transitional strategies adopted to contain the pandemic emergency can become a “new normal” also in the post-pandemic period. The paper belongs to a broader research project about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on new working spaces, which concerns the following two European research projects I am involved with: COST Action CA18214 “New working spaces and the impact on the periphery”, and CORAL ITN Marie Curie Project.

The studies on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the city identify the ‘dematerialisation of work’ as one of the most relevant effects, radically changing how many economic activities are produced and delivered. But what effects of the pandemic hurt the city, making it less attractive, ’emptying’ it? Is this a short-, medium- or long-term phenomenon? To what extent will the reduction of daily commuting in large cities allow knowledge workers to live and work in less central areas? Is it conceivable that the suburban and peripheral areas of the most prosperous cities will increase their attractiveness for these reasons?

Although the situation has not yet been wholly redefined, we can affirm that the pandemic has produced significant effects and, in particular (Mariotti et al. 2021a, 2022) : (i) the redefinition of the needs and functions of spaces for commercial and office use; (ii) the geography of work as suburban (and peripheral) areas are expected to become more attractive places to live and work; (iii) a new demand for working spaces for remote workers (please see note 1) (e.g. proximity coworking) will make it possible to enhance work-life balance and reduce commuting, with important positive repercussions on sustainability in terms of reducing traffic, congestion and pollution.

Regarding the first point, the need to ensure physical distancing has ’emptied’ offices and forced workers to carry out their duties in their homes (Florida et al., 2021). These are, in many cases, unsuitable places to work: they are too small or crowded or noisy due to the presence of school-age children. But COVID-19 has accelerated a phenomenon already underway, and that is destined to last: one-fifth of European employees will continue teleworking even after the pandemic. This circumstance is pushing companies to rethink their spaces. Instead of single offices or individual workstations, they are designing open, shared, and hybrid spaces suitable for socialising, which express greater attention to the dimensions of employee well-being. In addition, companies are opening geographically dispersed offices (hubs) to be closer to workers’ places of residence.

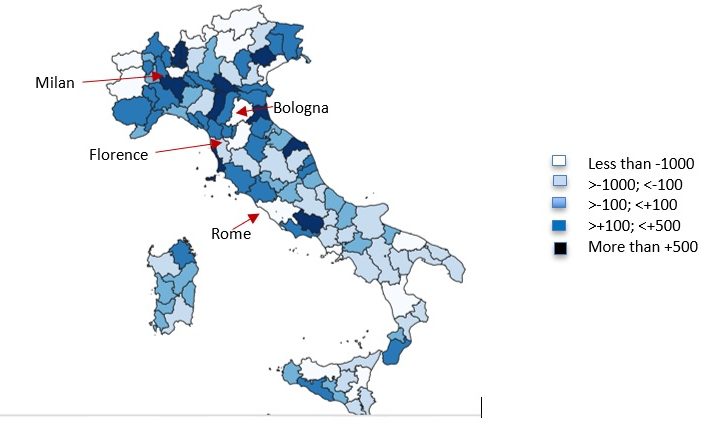

These changes significantly impact large cities that experienced a reduction in attendance by city users during the pandemic period. Figure 1 shows the exit from the large Italian cities.

Figure 1: Average (daily) change of the Facebook users by Italian NUTS3 provinces in March 2020 compared to the pre-Covid period (March 2019)

Source: Mariotti et al. (2021c), elaboration by Maud-DAStU on Facebook Data for Good

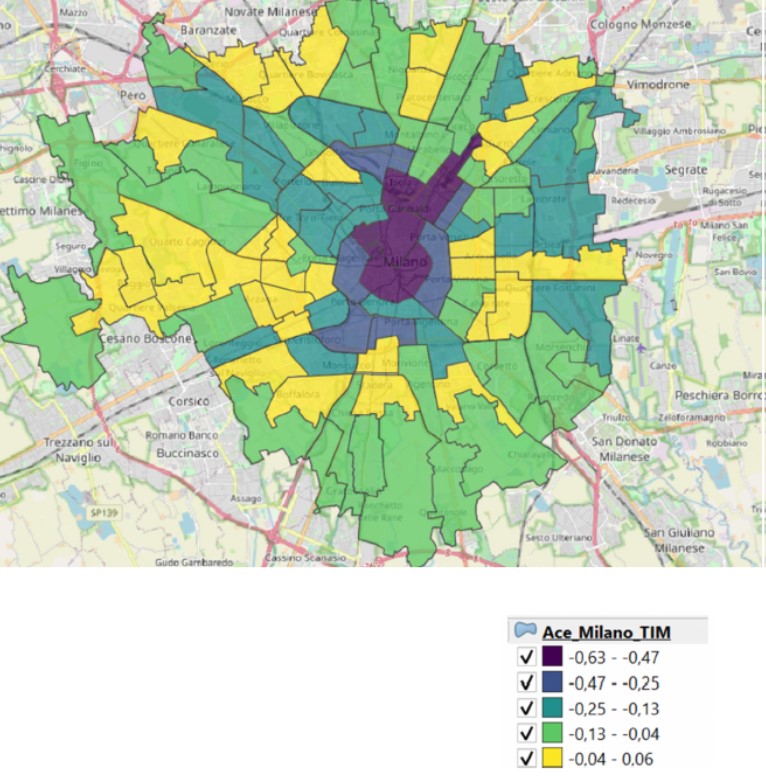

Besides, the central neighbourhoods of the city of Milan registered a 47% to 63% reduction in admissions in April 2020 compared to the same period in 2019 (pre-pandemic) (Mariotti et al. 2021a) (Figure 2). On the other hand, peripheral neighbourhoods and suburban municipalities became more attractive during the pandemic. Recent reports from real estate companies show an increase in demand for housing with larger floor areas than in the past, located in the outer crowns of the city, where values have already increased slightly (Nomisma, 2021).

Figure 2: Difference (%) of the monthly average hour of people presence (April 2020 and April 2019 by neighbourhoods-Census areas ACE)- TIM mobile phone data

Source: Mariotti et al. (2021a, p.34), elaboration by Maud-DAStU on TIM mobile phone data.

Remote working has also led to increased demand for workspaces (Mariotti et al. 2021b), such as proximity coworking, which can improve the reconciliation of work and personal care needs and reduce the home-work commute. The administrations of the major metropolitan areas are developing a solid debate on the form and functions of the city. They are promoting the idea of a more welcoming city that allows people to satisfy their primary needs within a 15-minute radius of their homes (please see note 2). In this context, new working spaces, such as coworking spaces, could no longer be just spaces equipped for carrying out work activities but become multifunctional environments (offering services for childcare, updating professional skills, aggregation, and socialisation, etc.) able to improve work-life balance (please see note 3). In this sense, the example of the first coworking spaces in Prague with babysitting services seems interesting (Bednar et al. 2021). In Norway (Di Marino and Lapinties, 2018) or Catalonia, coworking spaces within public libraries in suburban or rural areas are designed to reduce commuting.

Interview with Philip McCann

Mariotti: Some big-tech companies have stated that employees will continue to work mostly remotely even after the pandemic. What will be the impact on cities?

McCann: During the COVID-19 pandemic, many proximity relationships did not play their role because people could not meet and work together. Knowledge workers started to work mainly through Zoom, Teams, or other remote communication applications. This situation has produced adverse effects; however, some aspects are appreciated, and I imagine that many people will continue to work at home for a few days a week, even if they are not obliged to do so. This does not necessarily mean that cities will become less important. Indeed, many companies will change their organisational model: some employees will work full-time from home, some in the office, some in a flexible way – depending on the type of task, their inclination, and their needs and expectations. All this will have consequences on the use of space, blurring the separation between residential and productive space.

It seems to me that there are two important aspects. First, the evolution of business models: in a sense, what is happening is another shift in specialisation. Duranton and Puga (2005) in their article “From sectoral to functional urban specialisation” were right: firms are trying to become even more efficient by changing the distribution of labour internally, offering their employees flexible working opportunities. Secondly, there is the beginning of a new era of urbanisation. Second, there is a profound change in the real estate market: companies are already starting to dispose of office space (owned or rented), especially in city centres. This could create new opportunities for companies that have so far been unable to locate in the centre due to demand pressure and supply constraints.

From the competitive point of view, I think that the big companies will come out stronger in the end because they will reorganise their work even more effectively. For small companies, it will change less: they are organisations in which the entrepreneur is at the same time the general manager, chief financial officer, marketing executive, etc.. In this situation, the formal processes are less structured, the information flows are more direct and, in short, there is a need for an ‘on sight’ relationship. So, I think that small enterprises find it harder to adapt to the remote working model and will return to the traditional model as soon as possible.

Mariotti: So, we are not facing the end of the city as we have experienced it so far?

McCann: I think the crisis has made why cities are the best places to work even more apparent. People want to get back to living in the city, with its cafés, museums, theatres, they want to participate in events, be together, etc. Young people have a great need to return to the city. I think there will be a change in demand in the property market. There might be a drop in property prices in the city centre in the short term, but this phenomenon will not last long. After a while, there will be new demand, for example, from new economy companies looking for central spaces to increase their attractiveness to younger and more talented workers, who do not want to work in the suburbs. I imagine there could also be a restructuring of real estate, with the intervention of new private investors. Eventually, I think that as the campaign progresses and the economy recovers, the dynamics of the real estate market in the city will return to what they were.

At the same time, I think there could be a “reshuffling” of both owners and tenants, a kind of Schumpeterian phenomenon: some people who used to rent properties outside the city will now take the opportunity to move to the central area. Therefore, the most considerable effect will be a reorganisation of property ownership and employment. Above all, and this will have a longer-lasting effect, we will see changes in the design and redesign of urban spaces and structures, precisely concerning the different use of these spaces by businesses and individuals: open, flexible, multifunctional offices. Spaces dedicated to leisure (e.g., cafes, museums) and commercial activities might also change configuration.

The effects of agglomeration will still be significant, the pandemic will not make cities lose their role. On the contrary, history teaches us that after major crises, it is cities that drive recovery. What will change is that many people will be able to avoid, or limit forced commuting and may be able to go to the office 2-3 days a week instead of 5. The ‘new normal’ will be a new work-life balance. The important thing is to preserve time off work. The experience of the last few months has shown that the tendency to dilute working time is being realised. In short, with Zoom and Teams always open, we tend to work more longer. You don’t move for work, but the time you ‘save’ is immediately taken up by new work. And I don’t think this improves work-life balance at all.

Mariotti: What do you think about the role of new working spaces such as coworking and hybrid spaces to accommodate remote workers?

McCann: New working spaces will play an increasingly important role in cities because they are more flexible. Coworking spaces could also establish themselves as a model for organising work within individual companies: in a situation where workers only go to the office a few days a week, we need to make the most efficient use of that time, maximising the value of interactions and relationships – functions that shared spaces, typical of coworking, are best able to fulfil. I think the pandemic experience has shown that there is no alternative to face-to-face contacts, especially for those jobs that require a higher level of complexity. These activities can only be carried out at a distance up to a certain point: for example, only between people who know each other well and only for a limited period; on the other hand, when there are new people, you need to be together to create knowledge, trust, relationships. That is why cities have established themselves and that is why we still need them. The only thing that will change is that the city will be less and less a place of forced cohabitation, and more and more a place of voluntary cohabitation.

The risk is that only higher-income groups will benefit from these new opportunities. They have professions that are more easily adapted to online working and more flexible working practices. Of course, those who do manual jobs will continue to move to where the work requires it.

Mariotti: What are the main effects of the growth of remote working on central areas and suburban and peripheral areas? What will impact the change in property values in the different areas?

McCann: Some people imagine moving towards rural areas searching for an improved quality of life. This seems to be a simplistic view because of a trivial problem of land availability. Perhaps in the United States or Canada there might be the spatial conditions for a massive population shift to more peripheral or rural areas. Still, it certainly wouldn’t be possible in the UK or the Netherlands, where the availability of land is minimal.

As we were saying before, I think that the reduction of commuting will lead to a greater attractiveness and increase property values of suburban areas of cities. At least in the rich and strong cities. This could have a shadow effect on the second-tier cities, i.e. the hinterland of the weaker cities could start to overlap with the hinterland of the richer cities because of less commuting, which could lead to a different hierarchy of cities in terms of prosperity. For example, in the UK, the most economically marginal cities will become even more vulnerable; conversely, the hinterland of cities such as London, Edinburgh or Bristol will become more extensive. The pandemic will therefore widen the differences between regions. Capital will concentrate in prosperous cities, where investments will be safer and more profitable; conversely, economically weaker places will be riskier.

I don’t think prices will fall in the centre of big cities, except temporarily. After the COVID-19 pandemic, the economy will recover quickly and prices will return to their previous values, because the central functions of the city will remain the same and the need for social and professional relationships that they fulfil will not be easily satisfied otherwise. People rely on professional networks that are an essential part of their work. Young people do not want to live at home with their parents but want to return to the city, even at the cost of taking a few extra risks, which they scare them much less than the over 65s. The city will continue to be the place that offers young people the best job opportunities.

Mariotti: What do you think of the ’15-minute city’ as a strategy to reduce commuting and avoid the retail apocalypse caused by e-commerce?

McCann: I think it can work. The presence of retail is fundamental, not only economically but also socially. Shops are places to meet, exchange, relate, and share. Retail is a crucial component of the identity of a place. Without small shops, large areas of real estate are abandoned, and it is not easy to find new uses for them. I think, however, that without very incisive public policies, it will be difficult to counter the decline of retail, because the attractiveness of the e-commerce model and the strength of large platforms are enormous.

Conclusions and future research

The COVID-19 pandemic has in some ways confirmed Thomas Friedman’s thesis that mobile phones, email, and the internet have made the spatial location of people and businesses irrelevant; and people can work from home connected via the internet and meet the colleagues via Skype (Moretti, 2013). As we have seen, however, there are strong arguments that remote working will not empty the city. Agglomeration economies will always play an important role in cities, as will forms of proximity, and cities will remain the best places to work for many people and businesses. Cities are not merely a concentration of individuals but a complex and interrelated environment that fosters creativity. If the hinterland of more prosperous cities increases, there will be a reorganisation of real estate, the geography of work and workplaces. It is reasonable to expect that remote working will continue and there will be changes in the design of urban structures. Hybrid workspaces to be used for a few days a week are likely to be favoured, thus reducing commuting, and the paradigm that it is the work that should come closer to the worker will be espoused. The COVID-19 pandemic can be seen as an opportunity to reorganise working life and exploit the advantage of widespread remote working, especially in Italy, which has seen remote working grow from 10% in 2019 to 40% during the pandemic (Eurofound data) (please see note 4).

As Philip McCann suggests, the hinterlands of the most prosperous areas will be the ones that come out of the crisis best because they will become more attractive places to live and work. They will, nevertheless, produce a shadow effect on the economically weaker cities that will become more vulnerable. In addition, the reduction in the frequency of commuting and the increase in the distance of home-work journeys may impact the size of the hinterland of the most prosperous cities, including part of the hinterland of the most disadvantaged cities.

Within this context, another relevant issue concerns the role of parents with young children. It is important to experiment with valuable policies to accompany them in the labour market that invest in family-work reconciliation services. If remote working becomes a permanent feature, women will continue to take on most of the burden of unpaid inadequately recognised family care work.

Further research might focus on these extremely interesting and valuable insides by Philip McCann. This is the primary objective of two European research projects I am involved in: COST Action CA18214 “New working spaces and the impact on the periphery” and CORAL ITN Marie Curie Project.

References

Bednar P., Mariotti I., Rossi F., Danko L. (2021), “The evolution of coworking spaces in Milan and Prague: spatial patterns, diffusion, and urban change”. In Orel, M., Dvoulety, O., Ratten, V., eds., The flexible workplace: coworking and other modern workplace transformations, Springer Nature, pp.59-78.

Di Marino, M. & Lapintie, K. (2018). Exploring multi-local working: challenges and opportunities for contemporary cities. International Planning Studies, 1–21.

Duranton, G., Puga, D. (2005), From sectoral to functional urban specialisation, in «Journal of Urban Economics», 57, 2, 343-70.

Florida, R., Rodríguez-Pose, A., Storper, M. (2021), Cities in a Post-COVID World, in ‹‹Urban Studies››, 1-23

Friedman, T. L. (2005). The world is flat: A brief history of the twenty-first century. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

ILO, 2020. Defining and measuring remote work, telework, work at home and home-based work. ILO policy brief.

McCann, P. (2008), Globalization and Economic Geography: The World is Curved, Not Flat, in « Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society», 1(3): 351-370

Mariotti I., Manfredini F., Giavarini V. (2021a), La geografia degli spazi di coworking a Milano. Una analisi territoriale, Milano Collabora, Comune di Milano.

Mariotti, I., Di Vita, S., Akhavan, M. (2021b), eds., New workplaces: Location patterns, urban effects and development trajectories. A worldwide investigation, Springer, Cham.

Mariotti I., Di Matteo D., Rossi F. (2021c), Near working and collaborative spaces in peripheral areas during the Covid-19 pandemic, paper presented at the RSA conference 2021.

Mariotti I., Di Marino M., Bednar P. (2022), eds., The COVID-19 pandemic and the Future of Working Spaces, Routledge-RSA Regions & Cities Book Series – Regions, Cities and Covid-19, forthcoming.

Moretti, E. (2013), The new geography of jobs, Mariner Books.

Nomisma (2021), Terzo Osservatorio sul Mercato Immobiliare, Bologna.

Notes:

1: According to ILO (2020), the term remote working includes the following ways of working: teleworking, smart and agile working, and working from home.

2: The concept was popularised by the mayor of Paris Anne Hidalgo, who in turn was inspired by Carlos Moreno.

3: For a review on new working spaces, see the COST Action CA18214 “New working spaces and the impact on the periphery” and by the CORAL ITN Marie Curie Project.

4: Teleworkability and the COVID-19 crisis: a new digital divide?.