By Jason Deegan, University of Stavanger, Norway.

Introduction

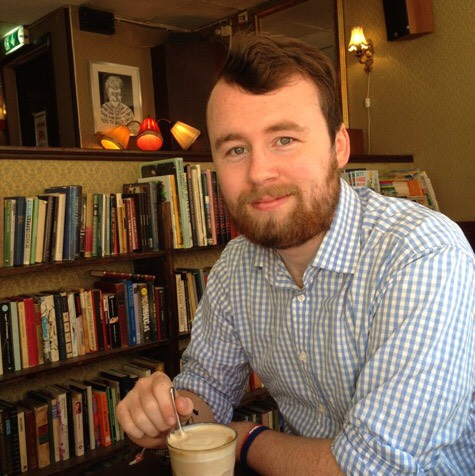

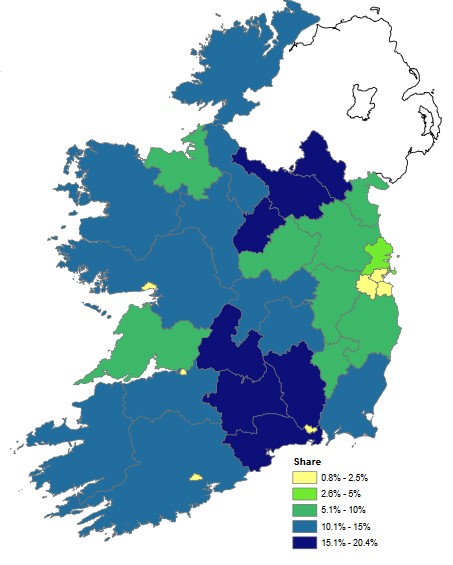

There has been much talk of the impact of a no-deal Brexit on one of Britain’s largest trading partners, and the one who is most likely to suffer the disastrous consequences of a no-deal Brexit. However, whilst a no-deal Brexit presents particular challenges to a number of sectors in regions across Europe, nowhere will the impact of a no-deal Brexit be more clearly felt than in Ireland (as demonstrated in figure 1 below). However, rather than building on the great work that is being done by regional science scholars (work which is beginning to unpack exactly what a no-deal Brexit might mean for regions across Europe), this article will look at Ireland and the challenges presented through a different lens.

Figure 1. Regional shares of local GDP exposed to Brexit, (Ortega-Argiles, 2018)

Rather than analysing a no-deal Brexit as a shock to Ireland in which little can be done, this article will instead cast a more critical eye on the shortfalls of regional policy within Ireland, and more specifically how Ireland’s already existent regional imbalances will only further come into focus due to the disruption caused by a no-deal Brexit. Rather than viewing such an outcome as an unknown, we will instead treat it as an externality to Ireland’s long-running policy failure of extremely unbalanced regional development, and in particular, the outsized role of Dublin and the surrounding commuter belt within Ireland’s economy. We can thus seek to explore what impact a no-deal Brexit will have on Ireland by looking at the opportunities such a situation presents to some regions in Ireland, and indeed the rather severe threats it poses to others.

Ireland is a complicated country in which to explore how its regions perform. Data collection on regional performance is frequently poor and difficult to access (Barrett et al., 2015), and in many cases the GDP distortions in Ireland’s economy will likely obscure the reality (Morgenroth, 2018) Indeed, some scholars go as far as to state that Ireland’s real economy should be disentangled from what essentially are “paper transactions” taking place almost exclusively within the MNC sector – the nature of which do little to provide an accurate reflection of the skewed structure of Ireland’s economy (FitzGerald, 2019).

To this end, the Central Statistics Office in Ireland have begun to integrate the use of a new measure of the economy, alongside measuring Ireland’s GDP. This measure, called the Modified Gross National Income or GNI*, seeks to exclude the distorting impacts of multinationals on the Irish economy in order to gain a more reflective picture of the true state of the Irish economy (Central Statistics Office, n.d.) With the modified GNI in mind, we can begin to construct an insight into what the true regional imbalances may look like in Ireland, and indeed to explore how a no-deal Brexit might further contribute towards the exacerbation of these imbalances.

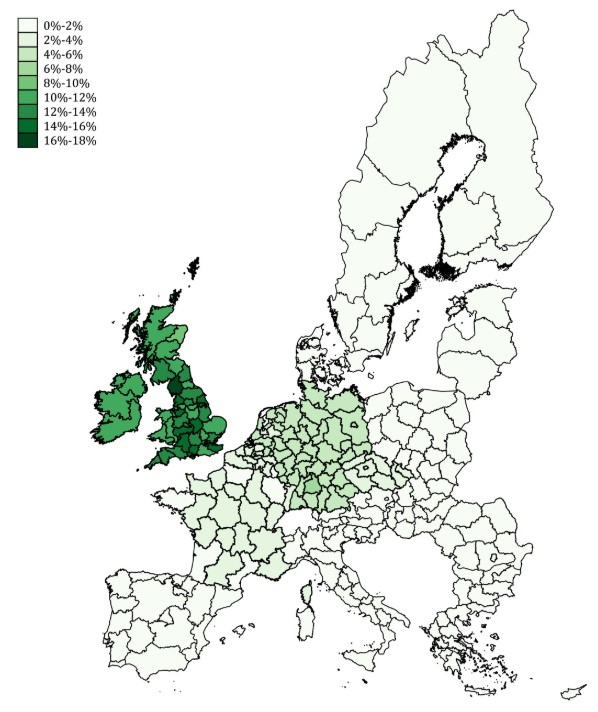

When we look at the significant expansion experienced in both the Irish economy and the Irish population during the 1990’s until the financial crisis of 2007-2013, we can see that much of this growth in population and economic activity largely took place within the Eastern regions of the country, and focused largely on Dublin. If we look at real total income as a measure of this expansion of economic prosperity, we can explore the nature of the divergence within income during the abovementioned time period.

Figure 2. Real total income per capita by region, 1991 – 2014, (Morgenroth, 2018)

We can see that consistently over the time period from the early 1990’s through to 2014, Dublin in particular and the surrounding Mid-East region in general frequently outperformed other regions, while the border region (of particular relevance to this paper) frequently performed the worst in the country. With the border region consistently struggling through this period, a period of relative economic expansion, it is likely that a situation wherein a no-deal Brexit and a hard border across the island will only further exacerbate the economic woes within this region. As will be shown later, this region (more than others in Ireland) is significantly more reliant on cross border trade, and any disruptions to this trade (for example in the form of a hard border, and customs checks) will lead to reduced trade flows overall.

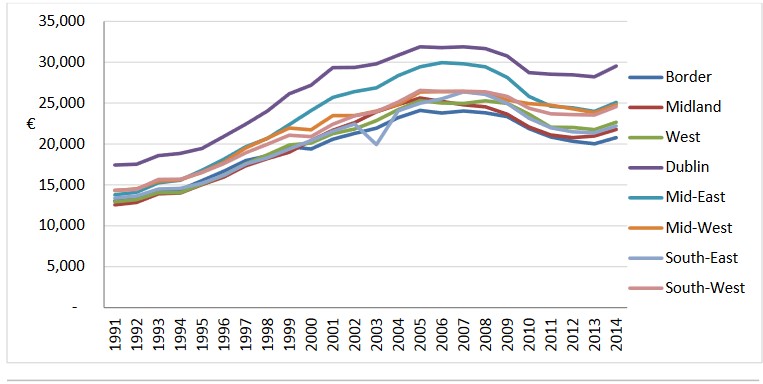

Similarly, whilst there is much talk of the potential benefits of capital inflows from firms and organisations seeking to move from a UK which is trading on WTO terms with the EU, to an EU member state, a scenario which it is assumed Ireland may benefit from, there is a considerable need for caution to be applied to this scenario. For example, as mentioned previously Ireland’s success in attracting FDI has frequently be skewed in favour of Dublin and the surrounding area more generally. It is important to note that the spread of this FDI in Ireland is highly concentrated, and as such, any further expansion to FDI in Ireland is likely to cluster around already existing patterns of FDI concentration as has happened in recent years. In the figure 3 below we can see the dominance of Dublin in attracting FDI as compared to the rest of the country.

Figure 3. Distribution of Foreign-Direct Investment in Ireland, (Morgenroth, n.d.)

Whilst there are concerns surrounding Dublin’s ability to continue to attract such high levels of FDI due in part to housing shortages and infrastructure problems within the city (as can be illustrated through abnormally large housing costs as compared to EU peer countries, and the levels of congestion within Dublin (O’Loughlin, 2019, Pope and Hilliard, 2019) the fact remains that the border regions have failed to secure an adequate share of the FDI pie – a problem which is unlikely to be addressed in the near future. Alongside the consistently low levels of real income within the region as outlined in figure 2, the failure to diversify within the border region will likely lead to further exacerbation of the economic problems within the region, given the increasingly likely scenario of no-deal Brexit.

However, of particular interest in the relationship between Ireland and the UK is the outsized role that Northern Ireland plays in the trade relationship between Ireland and the UK, namely that Northern Ireland accounts for between ten and twelve percent of total exports from Ireland to the UK and accounted for seven to eight per cent of imports (Intertrade Ireland, 2019). All of this is achieved with less than three percent of the total UK population. This is in large part caused by the integrated supply chains existing between Ireland and Northern Ireland.

A large portion of the trade across the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland consists of agri-food products, primarily dairy and beef in which the processing of the raw products takes place in integrated whole-island supply chains – for which a no-deal Brexit and a hard border would only lead to significant delays and reduce the flow of trade across the border, thus leading to a loss of competitiveness. Recently the Irish minister of Agriculture, Michael Creed, expressed his concern for the agri-food sector in particular as it is the most exposed economic sector and the one in which any disruptions of trade flows at the border are likely to be felt strongest in (Mcgee, 2019).

So how will this impact the border regions of Ireland? Due in part to the large share of employment within the agri-food sector within the border region as can be seen in figure 4, a no-deal Brexit coupled with the lack of alternative employment opportunities and the heavy reliance on agri-food is sure to lead to a situation whereby this region, due to its economic structure, is sure to suffer the worst from any no deal Brexit. A problem which successive attempts at dispersing the notable boom in FDI has failed to ensure a more widespread share of the gains throughout the regions of Ireland and which has left some regions notably more vulnerable to the shocks and disruptions caused by a no deal Brexit.

Figure 4. Share of Jobs in the Agri-Food Sector, (Morgenroth, n.d.)

That the Irish economy has drastically changed since the influx of foreign-direct investment within recent decades is well established within much of the literature on regional development in Ireland. However, the impact of this FDI, and the objective of successive governments to cater to the needs of MNC’s has led to a deeply unequal share of the spoils of this influx of investment. This has led to a situation wherein two economies are seen to exist within the Republic of Ireland – that of FDI and MNC’s which are largely focused around Dublin with some notable exceptions and what is more conventionally understood as the domestic Irish economy. Such a consistent regional policy failure has led to a number of regional imbalances across Ireland, which has led to a situation wherein an external shock such as a no-deal Brexit, and the hard border and customs check on the island (which are sure to flow from such a scenario) are likely to hit the regions which can least afford the negative impacts the most.

References

Barrett, A., Studnicka, Z., Siedschlag, I., Morgenroth, E., McCoy, D., Lambert, D., FitzGerald, J. and Bergin, A. (2015). Scoping the Possible Economic Implications of Brexit on Ireland. 48. Dublin: Economic and Social Research Institute, p.22.

Central Statistics Office (n.d.). Modified Gross National Income.Cso.ie. Available at:

FitzGerald, J. (2019). What is actually behind Ireland’s economic growth?. The Irish Times. Available at:

Intertrade Ireland (2019). Cross-border trade & supply chain linkages report. Intertrade Ireland, pp.7 – 9.

Mcgee, H. (2019). Creed admits all-Ireland agri-food economy ‘in some jeopardy’. The Irish Times.

Morgenroth, E. (2018). Prospects for Irish regions and counties. Scenarios and Implications. 70. Dublin: Economic and Social Research Institute, p.15.

Morgenroth, E. (n.d.). The Potential Regional Impact of Brexit in Ireland. Birmingham.ac.uk.

Ortega-Argiles, R. (2018). The Implications of Brexit for the UK’s Regions – City REDI Blog. Blog.bham.ac.uk.

O’Loughlin, E. (2019). Housing Crisis Grips Ireland a Decade After Property Bubble Burst. The New York Times.

Pope, C. and Hilliard, M. (2019). Dublin one of worst cities in world for traffic congestion. The Irish Times.

About the Author

Jason Deegan is a PhD Candidate at the University of Stavanger, originally from Dublin, Ireland his current work focuses on smart specialisation within Western Norway.