When the coworking space community makes the difference! Relevant support for the Ukrainian refugees

By Ilaria Mariotti, Associate Professor of Urban and Regional Economics, Politecnico di Milano – DAStU, Via Bonardi, 3, – 20133 Milan (Italy), email; Blanca Ella Monni, Community Manager at Betahaus, Rudi-Dutschke-Straße 23, 10969 Berlin (Germany), email.

In March 2022, the conflict between Russia and Ukraine reached its peak, resulting in the widespread displacement of Ukrainians and the devastating destruction of their homes and workplaces. Bomb attacks left offices and workplaces in ruins, leaving many individuals without a place to live and disrupting their means of earning a living. This Spotlight article sheds light on the “Coworking for Ukraine” initiative, which emerged as a response to the crisis, aiming to provide comprehensive support to the displaced Ukrainians affected by the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. Following the Russian Invasion of Ukraine, remote working and cloud servers, both within and outside the country, enabled many businesses to continue their operations. However, internet connectivity in Ukraine was and still is very unstable, negatively impacting citizens and workers who rely on digital services, particularly those who have been displaced. Many of these individuals have been forced to leave their homes and seek refuge either in other parts of the country or abroad. As described by Zhurbas et al. (2023), the western regions of Ukraine have become popular destinations for displaced IT workers. According to United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees-UNHCR (2022) data, more than 7,841 million refugees from Ukraine were recorded in Europe in December 2022. The highest number of recorded refugees was in Russia (2.8 million), followed by Poland (1.5 million), Germany (1.0 million), Czech Republic (470 000), and in Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom (with approximately 150 000 refugees). The demographics of these refugees differ from those of economic migrants: they are mainly women with children and older adults; the emigration of working-age men is limited due to Ukrainian legislation (Rossi et al., 2023).

A significant number of highly skilled knowledge workers, mainly specialised in the IT sector, have decided to relocate and embrace remote work opportunities in various European countries. Due to the worldwide disruption in coworking spaces (CSs), the One Coworking network launched the “Coworking for Ukraine” initiative. The primary objective of this initiative is to assist Ukrainians, beyond merely offering them basic amenities like a desk, Wi-Fi, and free memberships for three months. The “Coworking for Ukraine” initiative provides a comprehensive range of support services, including valuable information about transportation options like HelpBus and Flixbus, guidance on using platforms like AirBnB to find suitable living spaces, and more.

This paper provides an overview of the “Coworking for Ukraine” initiative and presents the results of a survey addressed to coworking managers. The survey, launched in spring 2022 by the COST Action 18214 – The Geography of New Working Spaces and the Impact on the Periphery (comeINperiphery), analyses the number of Ukrainians hosted in 2022 and the role played by the coworking community in helping them during such a difficult period. Twenty-four CSs responded to the survey, with 19 hosting 144 Ukrainians until spring 2022.

Coworking space and its community

Coworking spaces have become increasingly popular in recent years as a way for people to work together in a more informal setting. These spaces offer a variety of benefits, including increased productivity and opportunities for knowledge sharing and community building (Spinuzzi et al., 2019; Orel and Bennis, 2021). These spaces offer the benefits of community interaction, such as collaborating with fellow coworkers, while maintaining a sense of independence without the traditional hierarchies that usually dominate established communities (Jones et al., 2009). The users of coworking spaces primarily consist of individuals specialised in the creative industry, including self-employed professionals, freelancers, employees, and employers.

The literature on coworking spaces has underlined the importance of the community, the “sense of community” and the “care” and social support CSs offer their users. According to Neuberg’s declaration in August 2005 “in coworking, independent writers, programmers, and creators come together in community” (cited in Jones et al., 2009, p. 9). Capdevila (2015) pointed out that “one of the most important features” differentiating coworking spaces from shared offices is “the focus on the community and its knowledge sharing dynamics” (p. 3), and Capdevila (2014) claimed that “coworking is about creating a community” (p. 14) (cited in Spinuzzi et al., 2019, p.116).

“The concept of community refers to the possible relational implications of the co-location of workers within the same space and emphasises the role of coworking as a work context able to provide sociality to coworkers; spaces appear as environments in which relationships and interpersonal interaction can develop, not necessarily with effects in terms of professional relations and exchange of knowledge” (Parrino, 2015, p.265).

Creating a sense of community is one of the core principles driving these modern working spaces, where individuals who typically work independently come together (Akhavan and Mariotti, 2022).

Gerdenitsch et al. (2016) highlight CSs as valuable sources of social support for independent professionals, while Garrett et al. (2017) have underlined that the “sense of community” serves as a solution to combat social isolation experienced by coworkers. Furthermore, Clifton et al. (2019) state that the sense of community within CSs facilitates cooperation, collaboration, and knowledge sharing among coworkers.

In their study about Italy, Akhavan and Mariotti (2022) found a positive impact of community and social proximity on the well-being of coworkers.

A recent book by Mariotti et al. (2023) presents several cases of how new working spaces, including coworking spaces, have coped with the Covid-19 pandemic. These spaces have moved from face-to-face contacts to online or hybrid strategies to develop internal and external community ties to maintain the spaces’ sustainability and increase resilience to an exogenous shock like the pandemic.

This evidence demonstrates how coworkers showed a sense of solidarity with other CSs users, thus helping the community. The members of the CSs can therefore be defined as a community of practice capable of generating resources and ways of addressing recurring problems.

The analysis of the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on CSs in Italy reveals that CS managers made concerted efforts to maintain community engagement during lockdown phases. They achieved this by investing in communication channels and organising numerous online or in-person events while adhering to safety protocols (Mariotti and Lo Russo, 2022). Similarly, Trapanese and Mariotti (2022) described that, during the pandemic, the socio-cultural hybrid spaces in Milan strengthened proximity relations, collaborative welfare services, and the solidarity economy. Among the main initiatives was the collaboration with MilanoAiuta, which supported the community in catalysing energies and resources to face the tremendous social emergency that affected the most vulnerable people.

Finally, a recent study by Merkel (2023) discusses CSs as social infrastructures of care, illuminating the affective, emotional, and embodied dimensions of coworking contributing to coworking research; besides, she discusses CSs as everyday non-institutional care spaces.

Coworking spaces hosting Ukrainians: results of a survey

In spring 2022, Cost Action CA18214 initiated a survey targeting CSs managers from the 94 CSs affiliated with the One Coworking network, which promoted the “Coworking for Ukraine” initiative. The survey is comprised of seven sections: (i) location of the CS; (ii) number of Ukrainians hosted; (iii) age, sector and occupational roles of the Ukrainians; (iv) motivations for CS managers to participate in the “Coworking for Ukraine” initiative; (v) assistance provided by CSs to Ukrainians; (vi) relationship between Ukrainians and the coworking community; (vii) evaluation of the coworking community’s experience with the initiative.

Twenty-four CSs have answered the survey; of those 5 did not host and are not hosting Ukrainians. The nineteen CSs are located in Spain (17%), Czech Republic (13%), Hungary (8%), Italy (8%), Romania (4%), Slovakia 4%, Germany (4%) and Belgium (4%). About 88% are located in capital cities, e.g., Berlin, Bratislava, Bucharest, Budapest, Milan, Prague, Rome.

Before spring 2022, 144 Ukrainians have has been hosted by the 19 CSs, with an average of eight per CS.

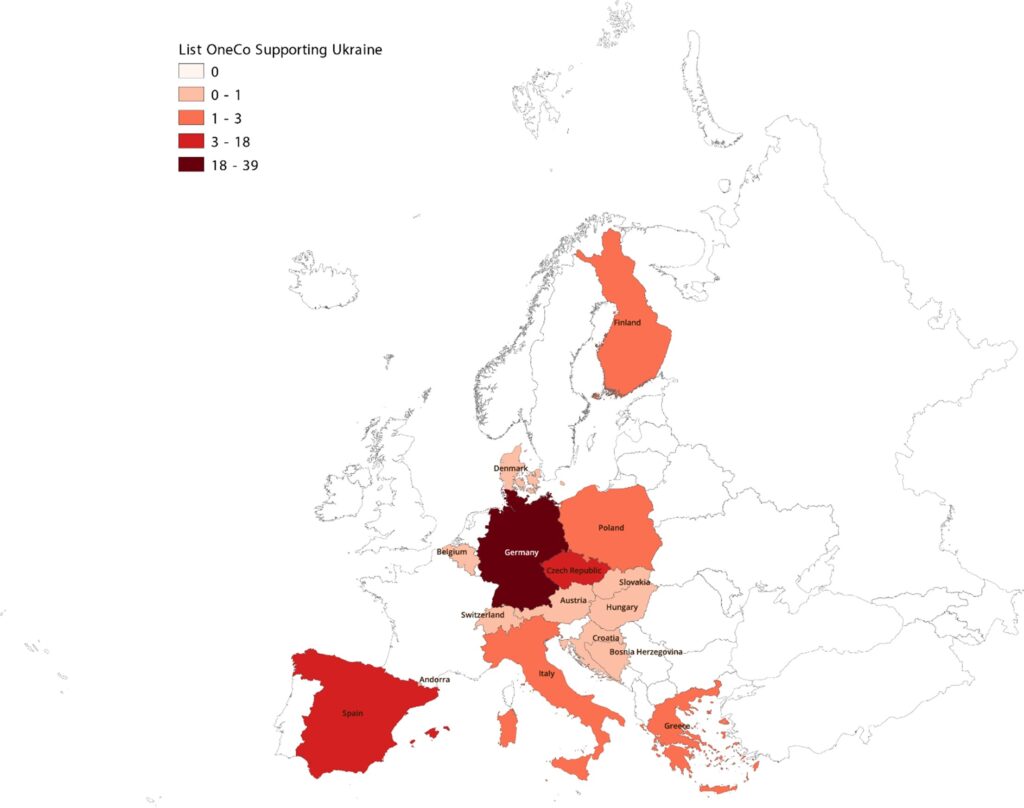

Figure 1: The location of coworking spaces (CSs) hosting Ukrainians in The location of coworking spaces hosting Ukrainians.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on One Coworking network data.

Regarding the hosted Ukrainians, the majority (80%) fall within the age range of 26 and 35 years, and they are: (i) freelancers (46%); (ii) employees (34%); (iii) entrepreneurs (10%); (iv) students (10%).

Several employees and freelancers work remotely for foreign companies. The main sectors of specialisation are Information and Communication Technology (33%); Architecture and Design(13%); Online marketing (13%); Media (4%); and other sectors (47%).

The findings indicate that among the surveyed Ukrainians, 11% were completely integrated into the coworking community, 68% partially, and 21% had limited integration. The collaboration proved to be more difficult, with 5% fully engaging in collaborative efforts, 37% partially and 58% poorly. Collaboration requires time, and not all Ukrainians consistently worked within the CS. Approximately 70% of the CS managers evaluated the experience positively, and 90% stated that the initiative met their expectations.

The survey showed that the “Coworking for Ukraine” initiative provided Ukrainians fleeing the war with the opportunity to establish new workplaces in foreign cities. These coworking spaces warmly welcomed them, offering amenities like free tea, coffee and meeting phone booths. Some spaces engaged in community actions, such as collecting donated laptops. Event spaces were provided for free for workshops and activities led by those affected by the war, such as yoga classes and specific afternoon activities. Social actions were fundamental to “connect the people and to make them experience a sense of belonging and normalcy”, says the manager of a CS in Berlin. Community managers facilitate introductions and connections between members, the local community and foreigners.

Furthermore, CSs organised fundraising events as a means to support Ukrainians and foster connections with coworking communities. One CS hosted a short film night and an artisan flea market organised by members to benefit those affected by the war.

Many members felt they wanted to collaborate even more and joined forces to visit refugee arrival stations, where they collected clothes and made sandwiches, providing people with primary goods and support. Notably, the survey highlighted the remarkable assistance and support provided by coworking and similar communities in helping refugees adapt in the new country. Communities mobilised themselves, and they provided language courses, support for administrative matters and paperwork. For example, at a CS in Alicante, Spain, the community helped Ukrainians find accommodations, while in many other cities, they actively supported the search for new jobs and opportunities.

Conclusions

As evidenced by recent research (Akhavan and Mariotti, 2022; Trapanese and Mariotti 2022; Merkel, 2023), it is now clear that modern working spaces have a significant and positive impact on society. They are environments that foster connections between humans and cultures and share inclusive values of help, support, and care.

The One Coworking initiative exemplifies the collective power and collaboration of coworking communities across borders. The support and assistance provided by CSs showcases once again the potential of coworking communities, not only from a professional and business point of view but also on a personal and social level. CSs serve as social infrastructures of care, offering everyday non-institutional spaces for support and well-being (Merkel, 2023).

Similarly, establishing new CSs in western regions of Ukraine to host IT workers, freelancers, employees, and businesses migrating from the eastern regions has been noteworthy. Zhurbas et al. (2023) underlined that these CSs are not just spaces to work but also to meet new people and form new communities. For persons who have escaped bombed areas, establishing new connections is crucial: CSs enable people to network and collaborate, fostering community and support.

Despite the challenges posed by the conflict, many workers living in Ukraine or abroad remain committed to building a brighter future for themselves and their communities. Their experience in Western Ukraine and Europe will probably help them create a more vibrant and prosperous Ukraine.

Acknowledgements

This publication is based on the work developed under the COST Action 18214 – The Geography of New Working Spaces and the Impact on the Periphery (comeINperiphery), supported by the European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST). COST is a funding agency for research and innovation networks. The authors thank Bruno Trapanese for drawing Figure 1.

References

Akhavan M., Mariotti I. (2022), Coworking Spaces and Well-Being: An Empirical Investigation of Coworkers in Italy, Journal of Urban Technology, 30:1, 95-109.

Capdevila I. (2014). Different inter-organizational collaboration approaches in coworking spaces in Barcelona. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–30.

Capdevila I. (2015). Co-working spaces and the localised dynamics of innovation in Barcelona. International Journal of Innovation Management, 19, 1–28.

Clifton N., Füzi A., Loudon G. (2019), “Coworking in the Digital Economy: Context, Motivations, and Outcomes,” Futures 135 (2019) 102439.

Cutini V., Averbakh M., Demydiuk O. (2023), Urban space at the time of the war. Configuration and visual image of Kharkiv (Ukraine), TeMA 1-2023, 7-26.

Garrett L.E., Spreitzer G.M., Bacevice P.A. (2017), “Co-Constructing a Sense of Community at Work: The Emergence of Community in Coworking Spaces,” Organization Studies 38: 6, 821–842.

Gerdenitsch C., Scheel T. E., Andorfer J., Korunka C. (2016), “Coworking Spaces: A Source of Social Support for Independent Professionals,” Frontiers in Psychology 7: 1–12.

Jones D., Sundsted T., Bacigalupo T. (2009). I’m outta here! How coworking is making the office obsolete. Austin, TX: Not an MBA Press.

Mariotti I, Di Marino M, Bednar P (2023) The COVID-19 pandemic and Future of Working Spaces. Routledge.

Mariotti I., Lo Russo M. (2023), Italian Experiences in Coworking Spaces During the Pandemic, in Akhavan M., Hölzel M., Leducq D., eds., European Narratives on Remote Working and Coworking During the COVID-19 Pandemic. A Multidisciplinary Perspective, Springer, 117-124.

Merkel, J. (2023). Coworking spaces as social infrastructures of care. In J. Merkel, D. Pettas, & V. Avdikos (Eds.), Coworking Topologies. New York: Springer, forthcoming.

Orel, M., Bennis, W. M. (2021). Classifying changes. A taxonomy of contemporary coworking spaces. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 23:4, 278-296

Parrino L. (2015), ‘Coworking: assessing the role of proximity in knowledge exchange’, Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 13: 3: 261–271.

Rossi, F., Kercuku, A., Mariotti, I. (2023). Demographic scenario. The case of Mykolaiv, presented at the UN4Mykolaiv Task force internal workshop, 2nd May, 2023, Milan.

Spinuzzi, C., Bodrozic Z., Scaratti G., Ivaldi S. (2019), ‘«Coworking Is About Community»: But What Is «Community» in Coworking?’, Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 33: 2, 112–140.

Trapanese B., Mariotti I. (2022), Socio-Cultural Hybrid Spaces in Milan Coping with the Covid-19 Pandemic, Romanian Journal of Regional Science, 16:2, 39-59.

UNHCR (2022) Ukraine Refugee Situation. Operational Data Portal.

Zhurbas V., Mariotti I., Orel M. (2023), The (re)location of coworking spaces in Ukraine during the Russian Invasion, in Mariotti I., Tomaz E., Mendez-Ortega C., Micek G., eds, Evolution of New Working Spaces: Changing Nature and Geographies, Springer, forthcoming.