Towards circular business models in the fashion industry: Entry barriers and drivers

By Janne Klahn, Master Student of the Master in Sustainability, Society and the Environment at Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, Germany

The fashion industry is following a mostly linear “take-make-waste” model and is one of the world’s largest polluters (Colucci and Vecchi, 2020; Howell, 2021). The industry is characterised by low product prices and quick adaptability to new fashion trends (Dissanayake and Weerasinghe, 2021). According to estimates, garments are likely thrown away after being worn only seven to eight times (Koszewska, 2018). The annual carbon footprint of the product lifecycle of the fashion industry is almost as large as the carbon footprint of all members of the European Union, which is 3.5 billion tons (Environmental Audit Committee, 2019).

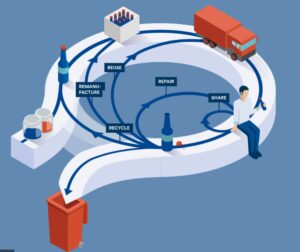

The harmful impacts of this industry could be considerably mitigated by replacing the linear model with a circular one. Circular business models are based on closed-loop production systems, in which resources are repeatedly used (see Figure 1, Todeschini et al., 2017). Despite the desire of the fashion industry to become circular, models based on the concept of Circular Economy (CE) are rarely and sporadically introduced. This article aims to identify the barriers and drivers that influence the implementation of circular business models in the fashion industry. Furthermore, two examples of business innovations based on circular principles will be illustrated.

Figure 1: The concept of Circular Economy (EPRS, 2021).

Entry barriers for circular business models

The following set of barriers can be obstacles to the implementation of a circular business model in the fashion industry:

- Barriers linked to supply chains: The globalised, complex, and fragmented supply chain is one major challenge in a circular fashion system. The supply chain consists of multiple actors and activities, making it challenging to ensure circular transparency and meet the environmental, health and social legislation standards (Koszewska, 2018).

- Barriers linked to government policies and expertise: The lack of government policies and expertise in the sector to achieve economic sustainability is another barrier. Systems are too bureaucratic and complex, and there are no clear government guidelines and policies to support the transition (de Aguiar Hugo et al., 2021).

- Barriers on the production side: In the phase of circular design development, an issue is that recycled materials are still a niche market and more expensive than their virgin counterparts (Colucci and Vecchi, 2020; Dissanayake and Weerasinghe, 2021). In recycling processes, the lack of material identification and sorting technologies is one of the main barriers, as manual sorting operations are labour-intensive and costly. Furthermore, the mix of materials and colours contained in the textiles are issued in textile-to-textile recycling regarding the economic feasibility (Dissanayake and Weerasinghe, 2021).

- Barriers on the consumer side: On the consumer side, lack of awareness is one of the main barriers to the transition to a CE. For instance, textile return systems are established in industrialised countries, but collection rates are low. In addition, most consumers still look for traditional fashion attributes when buying clothes and maintain their consumption patterns (Colucci and Vecchi, 2020; Dissanayake and Weerasinghe, 2021).

Drivers for circular business models

Besides the barriers, there are also drivers for circular business models, which transform a CE attractive:

- Profitability: CE models in the fashion industry can be very profitable for companies. For instance, service-based business models such as rental companies can reduce inventory and altogether avoid production (Todeschini et al., 2017). In addition, there can be cost savings through measures that reduce energy or water consumption and packaging waste (de Aguiar Hugo et al., 2021).

- Growing awareness of environmental issues: Another driver for CE practices is the younger generations’ growing awareness of environmental issues. These consumers pay more attention to topics such as sustainability, resulting in long-lasting competitive advantages for this business model (de Aguiar Hugo et al., 2021). Furthermore, some consumers avoid fast-fashion brands due to low product quality or unoriginal and mass-produced styles (Todeschini et al., 2017).

- Legislation: Although legal issues can pose a barrier to sustainable adoptions, legal issues can also be external drivers since they cannot escape environmental obligations. For instance, the European Union has set ambitious economic sustainability issues: “In 2050, we live well, within the planet’s ecological limits. Our prosperity and healthy environment stem from an innovative, circular economy where nothing is wasted and natural resources are managed sustainably.” (EPRS, 2021). In December 2015, as a part of the European Green Deal, the European Commission presented a CE action plan and legislative proposals on waste management, which were adopted in 2018 (EPRS, 2021).

Examples of business innovations based on circular principles

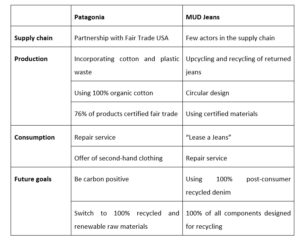

The following table summarises circular initiatives and future goals of two companies that aim to anchor the concept of CE in the company holistically.

Table 1: Measures of the companies Patagonia and MUD Jeans towards Circular Economy (own illustration based on MUD Jean 2018, 2020a, b; Patagonia, 2021a, b).

Conclusion and policy recommendations

The linear economic model that still essentially underlies the fashion industry must end in terms of sustainability goals due to its negative environmental impact. At the macro level, national governments must use policy tools to promote CE, change incentives, influence behaviours, build infrastructure, and create supportive institutions. Materials play an essential role in the circular fashion industry, so further research is recommended. Raw materials for textiles should be renewable or easily recyclable and not have environmental impacts.

References

Colucci, M. and Vecchi, A. (2020): Close the loop: Evidence on implementing the circular economy from the Italian fashion industryv. In: Business Strategy and the Environment; Vol. 30, pp. 856–873.

De Aguiar Hugo, A., De Nadae, J. and Lima, R. d. S. (2021): Can Fashion Be Circular? A Literature Review on Circular Economy Barriers, Drivers, and Practices in the Fashion Industry’s Productive Chain. In: Sustainability, Vol. 13, pp. 1-17.

Dissanayake, D. and Weerasinghe, D. (2021): Towards Circular Economy in Fashion: Review of Strategies, Barriers and Enablers. In: Circular Economy and Sustainability, Vol. 2, pp. 25-45.

Environmental Audit Committee (2019): Fixing fashion: clothing consumption and sustainability.

European Parliament Research Service (EPRS) (2021): Circular economy.

Howell, B. (2021): Top 7 Most Polluting Industries.

Koszewska, M. (2018): Circular Economy – Challenges for the Textile and Clothing Industry. In: AUTEX Research Journal, Vol. 18 (4), pp. 337-347.

MUD Jeans (2018): Sustainability Report 2018.

MUD Jeans (2020a): Eine Welt ohne Müll.

MUD Jeans (2020b): Sustainability Report 2020.

Patagonia (2021a): Our Quest for Circularity.

Patagonia (2021b): Our footprint.

Todeschini, B. V., Cortimiglia, M. N., Callegaro-de-Menezes; D. and Ghezzi; A. (2017): Innovative and sustainable business models in the fashion industry: Entrepreneurial drivers, opportunities, and challenges. In: Business Horizons, Vol. 60, pp. 759—770.