By Jeremy Chapman, Master Student of the Master in Sustainability, Society and the Environment at Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, Germany

While world leaders struggle to coordinate an appropriate response to the increasingly severe ramifications of global climate change, sustainable transformation projects are gaining a hold on a grassroots level in small cities and towns (SCTs) across Europe and elsewhere. The success of these projects demonstrates that even where resources are scarce, local governments may have the ability to dramatically improve their city or town’s economic and ecological resilience. We will take a brief look at sustainable transformation projects in Germany and their comprising strategies.

Prevalence and characteristics

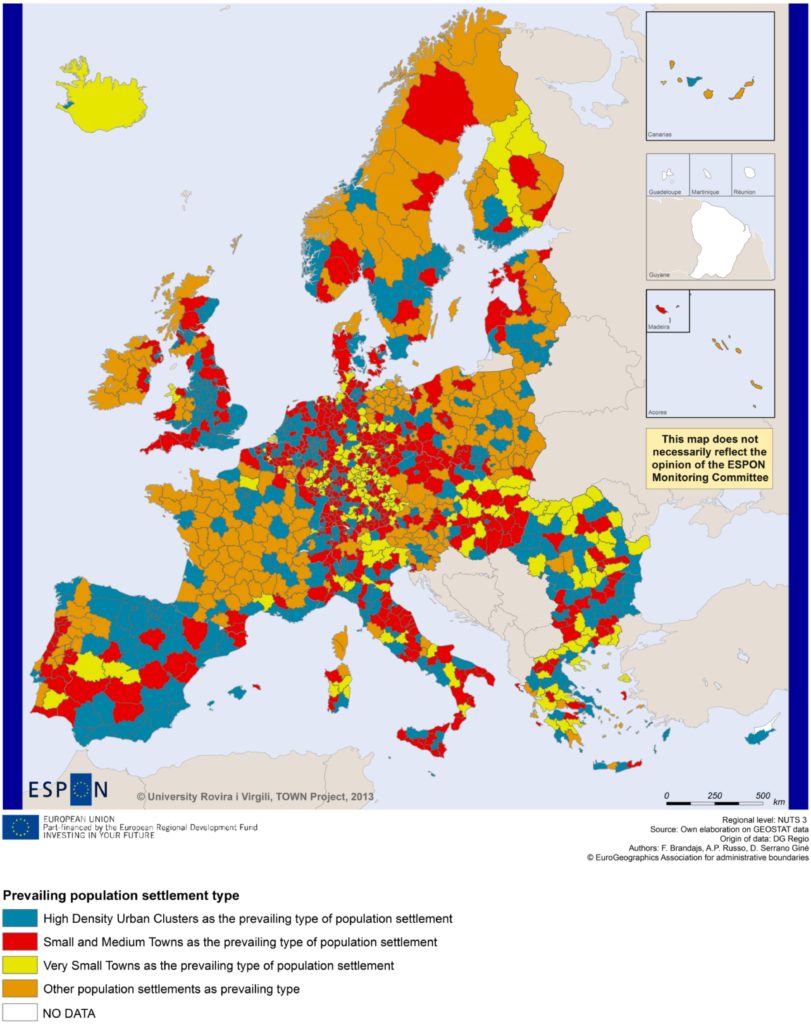

SCTs are a dominant type of settlement in several European countries, notably Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and the UK (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map showing the prevalence of settlements by type (ESPON, 2013). Areas dominated by SCTs are shown in red.

SCTs are settlements with between 5,000 and 50,000 inhabitants and have a distinct sense of place. This definition, therefore, excludes suburbs, highly fragmented settlements, and places that are recognisable only in name and little else. An incredible diversity of SCTs remain, each of which contends with a variety of challenges and opportunities within the framework of sustainable transition. Some of the fundamental characteristics of SCTs in this context are connectedness, demographic balance, housing affordability, proximity to nature, industry diversification, pollution levels, traditions and local engagement, social participation, and ‘slowness’. The applicability of these aspects to a particular small city or town are not just indicators of their resilience but also their growth or decline (Knox, 2013).

Notable Transition Movements

The following SCT sustainable transition movements all have grassroots origins in Europe. Some have a centralised model and are intended to be adopted by city and town officials, while others are specifically decentralised.

SEKOM – Eco-Municipalities

Origins

In 1983, the local council of a Swedish border town, Övertorneå, adopted the idea of becoming an eco-municipality from their Finnish neighbours. They documented and shared the effort with nearby towns, eventually creating the Association for Swedish Eco-municipalities (SEKOM).

Proliferation

100+ eco-communities in Sweden and 2500+ globally. Just 15 are found in Germany.

Notable features

- Detailed monitoring and publication of 12 environmental indicators. These can be used for comparing progress. Data is openly available, although currently only in Swedish.

- Sustainability and environment-focused, as opposed to resiliency.

CITTÁSLOW – the Slow City Movement

Origins

In 1999, the mayors of three small towns in Northern Italy came together to find a way to combat the invasion of fast food, fast traffic, and a fast pace of life in their communities. They developed the concept of the ‘slow city’ or Cittáslow.

Proliferation

272 Cittáslow member cities, 23 of which are in Germany.

Notable Features

- Membership is contingent upon a town’s commitment to a long list of development principles as well as undergoing special training.

- A holistic, customised approach which includes a consultation phase.

FAIRTRADE TOWNS

Origins

The Fairtrade Foundation was founded in the early 1990s and began certifying goods to “increase standards of living and reduce risk and vulnerability for farmers and workers” (Fairtrade, 2022). In 2001, the town of Garstang in the UK became the first to declare itself a Fairtrade Town.

Proliferation

The movement has spread around Europe and the US and now includes more than 2000 communities. Germany is its largest member country with 781 Fairtrade Towns.

Notable Features

- The membership process can be initiated quickly and by only a few people.

- Includes a marketing component, remarkably rare among transition networks.

TRANSITION TOWNS

Origins

The Transition Network is a grassroots community of cities, towns, and neighbourhoods, which started in 2007 in the UK.

Proliferation

1,086 globally, with more than 100 transition communities in Germany.

Notable Features

- Completely decentralised and encourages experimentation.

- Initially focused on eliminating the use of fossil fuels, but uses intentionally broad language to include other resiliency-building efforts large and small.

Within just these four programs, there exists a wide range of possibilities for SCTs to seize greater control of their fates in the face of contemporary global uncertainties. While some programs emphasize an organized holistic strategy, others seek to initiate transformation through smaller projects. There is an argument for each approach. Due to the complexities of SCT’s need to balance economic development with social justice and environmental protection, “small towns have to devise systemic solutions rather than one-off projects.” (Mayer, 2010) However, a smaller goal, such as becoming a Fairtrade Town, can help set a community on the path toward greater involvement in similar efforts. Indeed, several German Cittáslow members started their journey with Fairtrade Towns; one such example is Meldorf in North Germany. They are a particularly inspiring example of SCT sustainable transformation with how they have made great progress in a short time on limited resources. Meldorf is currently engineering a renewably sourced district heating system which includes a geothermal storage system, the first of its kind in Germany.

Resilience

It is important to distinguish between resilience and sustainability. Transition Towns founder, Rob Hopkins, notes that cities and towns can aspire toward sustainability, but that does not liberate them from external factors. Indeed, the first principle of Transition Towns is: ‘We respect resource limits and create resilience’ (Hopkins, 2008).

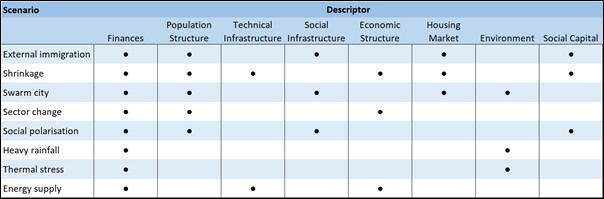

In Germany, there are published guidelines for creating Resiliente Städte (resilient cities). Rather than trying to become a movement through the grassroots organization, the University of Bonn and others have contributed to these guidelines which are intended to be used by SCT planners and officials (Figure 2). The guidelines go into detail and include a system by which to identify the vulnerabilities of a place and fortify those weaknesses. They have developed a ‘stress test’ so that SCTs can assess their vulnerabilities and identify areas of focus.

Figure 2. Part of the Resilient City stress test. Adapted and translated from BBSR 2018 / Bonn University.

Though this report is publicly available, it is not particularly accessible to the lay reader. Creating a condensed version and marketing it more broadly may help to raise awareness of this tool and promote its further implementation.

Low hanging fruit

The opportunity is ripe for SCTs in Germany and elsewhere to build their resilience while improving their quality of life. Regardless of which project a particular SCT joins, or if they join any at all, these programs have built an impressive open collection of resources, data, and materials to support transition efforts. The concepts they utilise have been tested and proved, and organizational templates are ready to be applied. SCTs can leverage their small size by planning, implementing, and scaling reforms quickly. This is not to understate the importance of quality leadership and political will, but the rest is already in place- ripe and waiting to be plucked.

References

ESPON (2013). TOWN Small and medium sized towns in their functional territorial context. ESPON & University of Leuven, Luxembourg.

Knox, Paul & Mayer, Heike. (2013). Small Town Sustainability: 2nd, revised and enlarged edition. Berlin, Boston: Birkhäuser, 2013.

Mayer, Heike & Knox, Paul. (2010). Small-Town Sustainability: Prospects in the Second Modernity. European Planning Studies, 18(10): 1545-1565.

German Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR). (2018). Stress test city – how resilient are our cities? Identify, analyse and evaluate uncertainties in urban development. Bonn University. ISBN 978-3-87994-224-4

Fairtrade and Sustainability (2022). What is Fairtrade?

Hopkins, Rob (2008). The transition handbook: from oil dependency to local resilience. Green Books. p.148-175. ISBN 978-1-900322-18-8

Tourism and Quality of Life in Cittaslow Cities (2022). Cittaslow.

SEKOM: Sveriges Ekokommuner (2022).