From Despair to Where? Can the Future Generations Act create a sustainable Wales?

DOI reference: 10.1080/13673882.2022.00001002

By Calvin Jones (email), Cardiff Business School, Cardiff, Wales, UK

“We hope that what Wales is doing today the world will do tomorrow. Action, more than words, is the hope for our current and future generations.” Nikhil Seth, Head of UN Sustainable Development, May 2015

Introduction

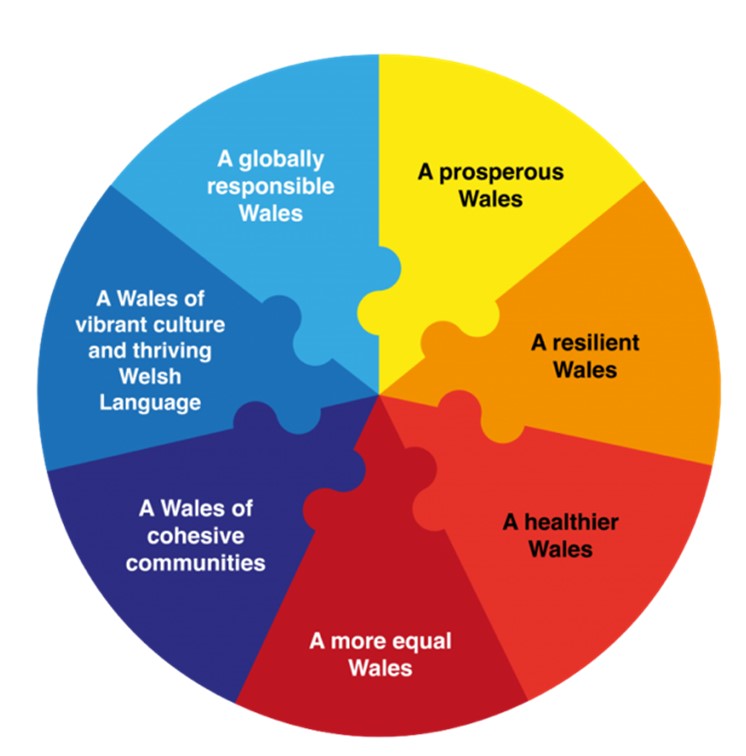

Blimey! It’s fairly rare that a Welsh economist (or for that matter anyone outside football) gets to feel smug about our international achievements, but this was certainly one occasion. Seth had seen something different and important in the Wellbeing of Future Generations (Wales) Act, passed that year in the Senedd, and intended to ensure all parts of Wales’ public sector – and the polity it controlled – considered how law, policy and regulation impacted not just people now, but people-to-be. With seven ‘goal areas’ ranging across health, prosperity, culture and global responsibility, and requiring five (better) ‘ways of working’, the Act is expansive in scope, holistic in framing, and, importantly, legally binding on 44 public agencies. It remains distinctive and at the forefront of attempts to reshape public policy to make it fit for the future – in the same way perhaps as the well-being budgets in New Zealand, or Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness. Yet it is a huge task to take a developed Western region – indeed one that is more carbon and energy-intensive than the national average – and make it climate and ecologically sustainable in any real sense. Is the Act – and Wales as a whole – up to the task?

Figure 1 The Future Generations Act Goal Areas (Welsh Government, 2015)

Welsh (Labour) Governments of the last few years can certainly point to green successes and green ambitions. For example, despite significant pressure from business lobbyists and the UK Government, plus a Planning Inspector who was unequivocally in favour, in 2019, the First Minister Mark Drakeford, cancelled the £1.6bn M4 relief road around Newport, citing both cost and environmental impacts. Since the election victory of 2021, the Welsh Government has gone even further, for example suspending all new road-building schemes, and promising to plant 86m trees in nine years (and create a new National Forest). As I write, the Ministers in the sprawling Climate Change department are preparing a new law enabling a single bus network and ticketing across Wales – with both climate and social objectives. This is, it must be said, all good stuff – and especially compared to the fragmented, inconsistent, and hands-off approach that has reigned across Offa’s Dyke in recent years. But there is so far little sense of the seismic change in approach across the public sector – and by extension Wales as a whole – that the climate science demands.

The Big Issues

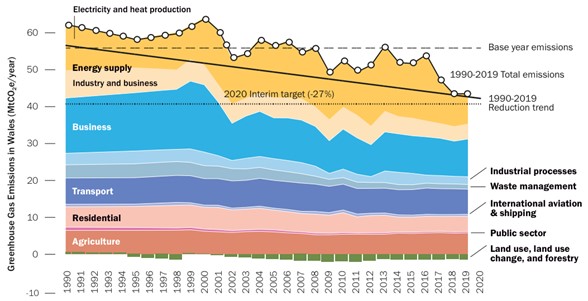

On the big-ticket item, reduction in climate emissions, despite grand plans, Wales has performed poorly over decades, with little discernible change since the Act was passed (see Figure 2). Reductions in territorial emissions since 2010 have occurred almost wholly due to the decarbonisation of the – non-devolved – UK electricity grid. Welsh Government might hope to piggyback future decarb here in its support of UK Gov new-build nuclear ambitions in Wales, albeit with no explanation of how the treatment of consequent radioactive wastes might impact future generations, or where Wales’ responsibilities lie. Meanwhile, there has been no significant progress on decarbonising heat and buildings, transport, or industry (where support for the big players, including Tata Steel remains a dubious-technology-fix-enabled sacred policy cow). Welsh. Unhelpfully, for the overall narrative, April 2022 saw the First Minister out celebrating the launch of nine new holiday air routes from Cardiff Airport, which is owned by… the Welsh Government.

In essence in fact, despite the Act and the quite different approach of governments in Cardiff Bay and Westminster, Wales remains… a small bit of the UK; much the same in its lifestyles, attitudes, impacts and futures, albeit with some modest differences in public policy. Why has this notionally transformative Act transformed so little?

A first reason (and one the Welsh Government would probably cite) is the limited autonomy, and discretionary resource afforded to Wales in the current devolution settlement – indeed an autonomy that, under the Internal Markets Act and organisation of post-EU regional funding, is decreasing in practice. Even following the UK Parliament Wales Act of 2017, which for example allowed modest regional tax powers, it is impossible for the Welsh Government to borrow significant sums for capital investment – not more than £150m in any year – and even then, only with the say-so of the Treasury. Offering financial support for, say, a new tidal lagoon to decarbonise electricity or wholesale national eco-retrofit, or perhaps the purchase of very significant assets becomes extremely difficult. Meanwhile, the lack of control over key infrastructures (e.g., electricity grid) and lack of levers in ‘reserved’ areas like employment law, and macro/finance has implications. For example, a truly zero-carbon transport system might emerge with the electrification of the South Wales Metro but Wales’ second city, Swansea, must ‘whistle’ for electric and stick with diesel (even as London moves to Crossrail 2). And projects which might have significant climate co-benefits – for example, a Universal Basic Income – stay effectively on the starting block, as in Scotland, without UK Government support. And meanwhile, the Aberpergwm mine in South Wales embarks on the excavation of 40 million tonnes of coal under a UK Coal Authority license.

There is then much to be said for the straitened policy circumstances in which Welsh Governments find themselves but secondly, it is also true that even in fully devolved areas, progress on eco-transformation has, since the inauguration of the first Welsh (Assembly) Government in 1999 and since the 2015 Act, been slow. Observing the Act and government “in action”, one is left with a feeling of ‘processification’, where radical framings and objectives are swallowed by public agencies, fitted within existing programmes and budgets, the difficult corners knocked off, and then regurgitated as aspirations and activities that are incremental, unchallenging, and thus largely unimpactful. The (convoluted) shaping and delivery of the Future Generations Act is in part to blame. Responsibilities for guidance, delivery and ‘naming and shaming’ laggards are split between the Office of the Future Generations Commissioner and the Wales Audit Office. The Commissioner’s office and budget are tiny for such a huge task – two dozen employees and a few million pounds annually. Objective setting (via wellbeing assessment and targets), implementation and audit thus become self-directed by each of the 44 agencies, with some external quality assurance, but inevitable unevenness and gaming. The continuance of prior structures and habitus means levers that are critical in changing wider behaviours remain un-pulled. Procurement directors, as one memorably told me, remain not at the ‘top strategic table’, but in the very un-strategic car park.

A third reason that the Future Generations Act has not seen the upending of public sector policy and structures in Wales is the usual simple-but-complex electoral arithmetic that faces all politicians. Despite their healthy showing in the 2021 elections and kudos buoyed by policy response to the COVID pandemic, Welsh Labour has been (with a few exceptions) relatively unwilling to engage in policy discussions that might cause a significant electoral upset. For example, even where the Future Generations Commissioner has (with the aid of this very author) repeatedly called for a complete overhaul of education and training in Wales, to make it ‘fit for the future’, including the scrapping of public, standardised exams at age-16 (GCSEs) and a new education levy to increase spend-per-pupil the response from Government, Qualifications Wales and the exam board was not debate and negotiation but… tumbleweeds. There are no votes in increasing taxes, or in making it harder for nice middle-class parents to discern the best schools, so the possibly-most-important part of facing the future – up-skilling our children – simply goes undone. Several other conversations – on our ability to protect homes from flooding, on the cost and availability of energy, and on unsustainable consumption of various sorts simply loom quietly, struggling to be born.

In the end, the Future Generations Act (and more radical elements of the political class in Wales) are up against the fearsome task of unwinding an economic model and social settlement built on hundreds of years of fossil fuel (and Global South) exploitation, which has bred entitlement deep into the bones of people in Wales, as in other parts of the UK; an entitlement bolstered by four decades of being trained to engage in society as consumers, not citizens. At some point, people in the West will be faced with the stark reality that no imminent technology fixes will fit the square pegs of regular international holidays, biennial new iPhones and 2,000kg electric vehicles into the round hole of a liveable planet. But to engage in this conversation requires the Government in Wales to interfere and shape consumption decisions in a way few governments relish – especially against the backdrop of the well-remembered COVID restrictions. A UK Labour Party that tweeted recently encouraging the Conservative government to crack down on anti-oil climate protests is probably also a consideration in this particular case.

In this interregnum, the monsters of fanciful ‘green deals’ live, promising that all manner of things will be well if we only take the little steps… whilst science increasingly points the other way.

What Prospects for Improvement?

This is a perhaps depressing summary of the challenges, but Wales is still ahead of other UK regions in its focus on climate change, and with an increasing raft of policies and (modest) investment which may pay (modest) dividends. As with earlier successes, when Wales transformed its domestic recycling rates future progress might be less to do with letters of the law than with the spirits of politicians. Then, it was environment minister Jane Davidson who, when in the 2007-11 Welsh Government, also inaugurated the UK’s first plastic bag charge, and set the path towards the eventual Future Generations Act. Now it is the Climate Change Minister and (an especially forthright and honest) Deputy Minister. In each case, and despite the silos that bedevil Welsh (and all cabinet) government, progress has been made on the back of determination and a willingness to take an electoral risk. The downside being, of course, that the departure of ministers can see progress – on even these existential issues – stymie, as happened in Wales after 2011. However, the near dominance of Welsh Labour in Welsh governments since devolution – with little sign of this weakening even as UK Labour has struggled – might see a longer-term approach develop across the party (and perhaps including the largely-aligned Plaid Cymru). After all, if one is likely to still be governing in 2030, or even 2050, then developing policies (even painful ones) now to help make that polity functional and governable might recommend themselves.

It is also notable that the devolution settlement in the UK is… less than settled. As the Conservative Government chips away at devolved power, the Scottish National Party “push” for a second referendum on Scottish independence, and Irish reunification becomes increasingly likely, Wales faces a continuum of futures – ranging from being little more than an ITL1 (note: Since Brexit the former EU NUTS area classifications have been replaced with International Territorial Level designation, albeit with the same boundaries) region of a rump-UK, through to full political independence – voluntary or otherwise. The latter would change the context completely: with the withdrawal of UK social security safety nets and support for public spending (required due to Wales’ poor tax base), a new economic approach would be required – the shape of which would be open to deep debate, with perhaps a more radical – and climate-friendly – outcome than is currently possible. Or indeed something worse.

Conclusion

“It is a file of shame, cataloguing the empty pledges that put us firmly on track toward an unliveable world”. Antonio Guterres, U.N. Secretary-General, April 2022

It is hard to escape the conclusion that even a far-reaching, legally binding and deliberatively integrative project like the Wellbeing of Future Generations is wholly insufficient to respond to the science as starkly presented by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) 6th Assessment Report on climate change, or indeed the wider and related nature emergency. Whilst the Act has led to or at least underpinned and reinforced actions that place Wales ahead of the eco-game, transformation, either of public sector activities under the Act, or more generally within the region, seems a long way off. The notion that the first region into the industrial carbon age might be the first out is fanciful.

Figure 2. Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Wales (Welsh Government, 2021)

The Act and wider sustainability policy are so far failing to put Wales on the war footing that is required: one whereby all regional resources and minds are bent towards the goal of mitigating climate emissions, protecting what remains of nature, and increasing the resilience of people and places to the now-inevitable climate impacts. This failure is perhaps unsurprising, given the limits of the Welsh government. Why should Tesco, or Boris Johnson, care about the Future Generations Act?

The lesson of COVID, as planes once again fill the skies, is that we are capable of wasting any number of good crises. But the fact remains that unless some way can be found at all scales; regional, national, and community to make climate and nature the critical lens to guide all regulation, policy, and activity, then we face a future that is intensely bleak.

This is, of course also true for academics like us.

Bibliography

Hickel, J., Dorninger, C., Wieland, H., & Suwandi, I. (2022). Imperialist appropriation in the world economy: Drain from the global South through unequal exchange, 1990–2015. Global Environmental Change, 73, 102467

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2021) Synthesis Report of the Sixth Assessment Report Available from https://www.ipcc.ch/ar6-syr/. Accessed 25th April 2022

Jones, C. (2019) Education Fit for the Future in Wales Future Generations Commissioner for Wales, Available from https://www.futuregenerations.wales/resources_posts/education-fit-for-the-future-in-wales-report/. Accessed 25th April 2022

Jones, C. (2022) What would be the central economic issues around independence for Wales? Economics Observatory Nations, Regions & Cities, March 2022. Available from https://www.economicsobservatory.com/what-would-be-the-central-economic-issues-around-independence-for-wales. Accessed 13th April 2022

Welsh Government (2015) The Wellbeing of Future Generations Act (2015); The Essentials Available from https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2021-10/well-being-future-generations-wales-act-2015-the-essentials-2021.pdf. Accessed 25th April 2022

Welsh Government (2021) Net Zero Wales: Carbon Budget 2 (2021-25) Available from https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2021-10/net-zero-wales-carbon-budget-2-2021-25.pdf. Accessed 25th April 2022