John Rennie Short discusses his new book, The Unequal City Urban Resurgence, Displacement and the Making of Inequality in Global Cities

Interview by Joan Fitzgerald, Editor-in-Chief, Regions and Cities Book Series

Northeastern University, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

John Rennie Short, is Professor of Public Policy at the University of Maryland, US. He is an expert on urban issues, environmental concerns, globalization, political geography and the history of cartography. He has studied cities around the world, and lectured around the world to a variety of audiences.

His most recent book in the Routledge-RSA Regions and Cities series is The Unequal City

Urban Resurgence, Displacement and the Making of Inequality in Global Cities

Joan Fitzgerald (JF): This is your 48th book! How do you do it?

John Rennie Short (JRS): Well, I never work after 5:00 or weekends. I work intensely and when I get blocked I move to less intensive work—looking up sources, adding references, etc. Then back to writing. So, my advice to others is to know when to stop to be productive. Writing never gets easier but it gets less painful!

JF: What motivates you to keep writing?

JRS: I have lived a privileged life and have a strong desire to make sense of the world for myself and other people. I do that in my books. I still write articles, but the book form is more accessible to more people. And I write because I’m always thinking of ideas. At my age, I am aware that I don’t have unlimited time—so I better do it now.

JF: What motivated you to write The Unequal City?

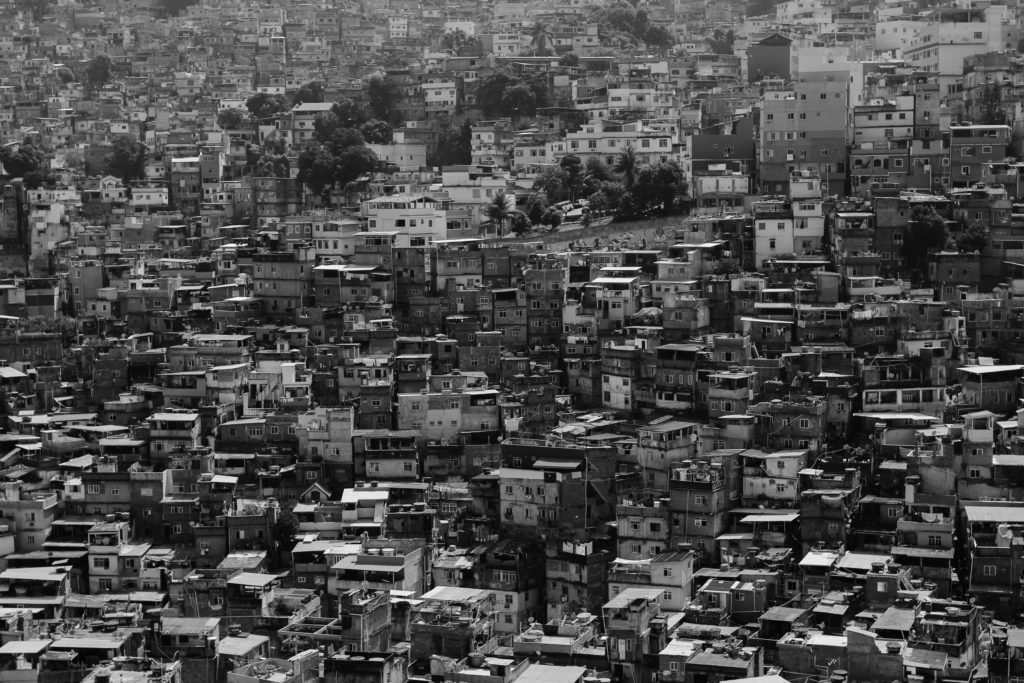

JRS: I was working on a technical paper on population change in U.S. cities and noticed that something different started to happen in about 1990. It was the first time in decades that cities began to gain population relative to their suburbs. Then I went to international data—Paris, London, Berlin, Shanghai and saw the same trend everywhere I looked. And I could see it on the ground as well—high-end condos and mega projects are going in all global cities. I tried to make sense of it. What has become the accepted explanations, neoliberalism or gentrification, in my view have lost their meaning for me. They are the end of the argument, not the beginning (and the end). I wanted to go deeper.

The first trend I examined was the rise of enormous pools of mobile capital. Whether the Sovereign Oil Wealth Fund or the Canadian Public Service Union, they need big safe investments like real estate. With the globalization of capital flows we see these funds investing in big cities all over the world, turning liquid capital into fixed capital. And of course, high-end development has higher returns. But of course, there has to be demand for these investments to pay off.

On the demand side, the rise of the middle class and demographic changes are driving demand for central city housing. There are also more rich individuals looking for investments and they too are parking their money in urban real estate. The demographic trend is that, in many cities, almost 50% of households are single person—they have different demands and are looking for denser, car-free city living.

What you see is cities increasingly trying to attract rich. There’s a shift to changing the city to meet needs of the wealthy. The neoliberal city.

JF: You have a chapter, Contesting the Unequal City. How is that happening? Where is it working?

JRS: Often citizen groups fight against specific outcomes of this shift—particularly the lack of affordable housing. There is more conflict rather than just the superrich have their way entirely. Democratic forces have a better say at the city than the national level. Even in places like China, for example, the urban middle class is demanding better air quality.

JF: Any closing thoughts?

JRS: One of the things that struck me in writing this book is the rise of city states—you see this alternative urban republic—urban networked world. Shanghai is closer to New York City than rural China. World cities have more in common with each other than with towns in the hinterland. The big architecture firms are putting up the same type of buildings all over the world. The same practice, ideas and buildings are circulating around the global city network being tweaked and changed as well as implemented and adopted.

Trying to make sense of these rapid and large changes s has reinvigorated my interest in cities.