A tale of two cities: Housing deprivation in Sydney

DOI reference: 10.1080/13673882.2021.00001084

By Khandakar Farid Uddin and Awais Piracha, Western Sydney University, Australia.

Introduction

Australia is one of the most urbanised countries in the world. More than 86% of people in Australia live in a large metropolitan area along its coast (statista.com, 2020). Sydney, the state capital of New South Wales (NSW), is the largest Australian city. It is routinely ranked in the top ten of the most liveable cities in the world. Sydney is a modern and vibrant city and a substantial concentration of global business and economy. Greater Sydney Metropolitan area covers of 12,300 square kilometre area. Sydney’s population in 2019 was 5,312,163 (.idcommunity, 2000), that is almost two-thirds of the NSW state’s entire population. Greater Sydney has 33 Local Government Areas (LGAs) and more than 900 suburbs.

Greater Sydney is Australia’s economic heart. Its vibrancy is essential to drive the NSW and national economies. Due to fast economic and population growth, Greater Sydney has been facing growing land and housing demand. That has hard-pressed the state government to boost housing supply. In the first two decades of the 21st century, the state government introduced various strategies to increase housing supply in the Greater Sydney regions. As a consequence of the state’s intervention, the demographics of Greater Sydney has been transforming. As a result, Sydney has been expanding towards the west and is anticipated to expand more. However, the existing policy and practice governing this urban growth are leading to geographical disparities. Data shows that urban planning policy and metropolitan strategies are dumping new housing in western Sydney, which lacks transport infrastructure, employment opportunities, and amenities and is too hot in summer.

Objectives and significance

Housing and urban research is a well-traversed area in Australia. However, the issue of housing generated deprivation has not been noticed in academic thought in Australia. The current academic literature focuses on social housing, homelessness, housing affordability or housing informality. There is a dearth of work on the consequences of deprivation generated through new housing location. In terms of housing supply strategies, locational deprivation is inadequately acknowledged in the existing strategies for the provision of additional housing and population. Thus, the principal aim of the study is to reflect how Greater Sydney’s residents are being forced to the deprived situation because of housing location.

This article provides an overview of the historical context to recent housing approvals and attempts to answer the question: “how the provision of housing generating deprivation related to urban amenities in the Greater Sydney Metropolitan area?” This research argues that along with the existing socio-economic divide, Greater Sydney’s housing approval practices are also differentially divided, which is causing added adverse effects for the western Sydney neighbourhoods. It emphasises the need to search for a rational housing approvals policy and highlights the need for job opportunities, urban amenities, ecological balance and sustainable development for the disadvantaged communities in western Sydney.

Methodology

This study applies qualitative research methods. This study investigated the housing approvals data and analysed housing generated deprivation by exploring secondary sources of data from newspapers, journal articles, reports, websites and other materials from NSW government sources. The study used Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) and NSW Government’s Department of Planning, Industry and Environment (DoPI&E) data to reveal the housing location trends and socio-economic disparities of Greater Sydney areas. The ArcGIS mapping software is applied to create a significant map to show the demographical diversity.

Conceptual overview

Housing is an essential need which impacts the survival and well-being of individuals (Wong and Chan, 2019). It plays a crucial role in everyday activity and determines an individual’s conditions (Dunn and Hayes, 2000). It ensures individuals welfare by safeguarding elementary requirements and recommends lively civic life (Wong and Chan, 2019). Besides, housing is crucial in the production and distribution of wealth and opportunities (Dunn and Hayes, 2000). Housing associated difficulties are also linked with socio-economic disadvantage and deprivation (Wong and Chan, 2019). Sen (2000) defines deprivation as a situation where individuals are not being able to utilise the full potential of the social order, being left out from the broader opportunity and unable to fulfil the needs of life due to socio-economic disadvantage. Herbert (1975) also claims that deprivation infers a below standard living where most individuals in society face adversity and insufficient access to resources. Therefore, it is apparent that housing placed in the disadvantaged areas where individuals do not have access to good jobs and urban amenities would lead to housing related deprivation.

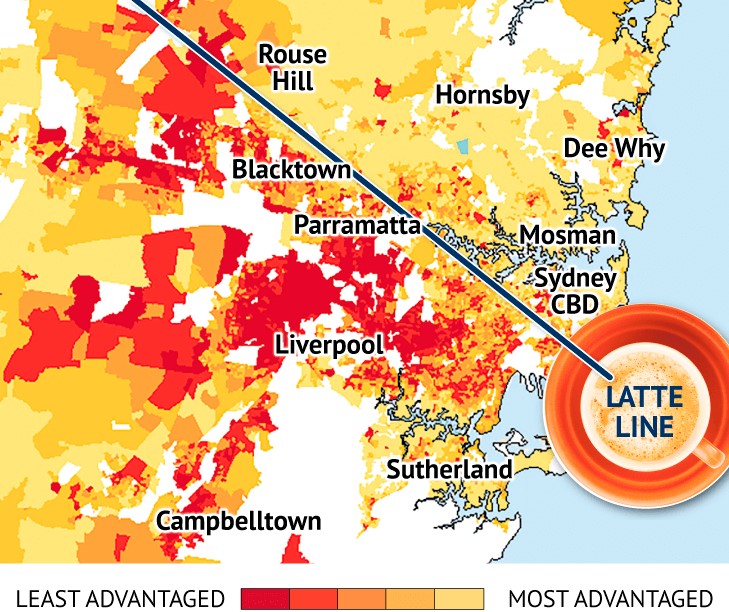

Greater Sydney division

Greater Sydney is divided into advantaged and disadvantaged areas by considering various socio-economic needles (Figure 1). A slanted line from north-west has identified the division of Sydney to the south-east. The line divides the most advantaged north and east from least advantaged south-west and west.

Figure 1. Advantaged areas of Sydney

Source: The Sydney Morning Herald.

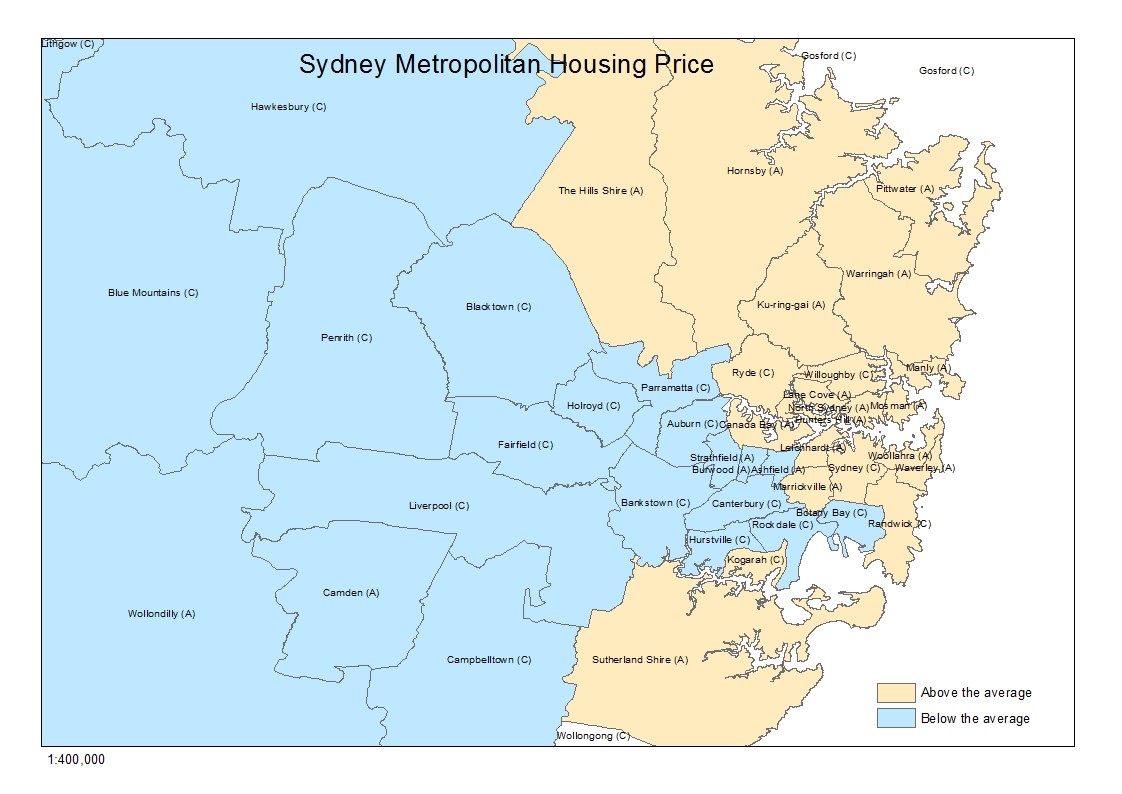

The advantaged areas are closer to jobs, good schools and well access to urban facilities. The advantaged areas are very expensive and unaffordable for the disadvantaged area’s people. The housing prices are remarkably higher (figure 2) in advantaged areas; consequently, most of Sydney residents cannot consider buying a property there. Besides, property prices in advantaged areas are growing faster, because the demand of housings is higher and the supply is lower.

Figure 2. Housing prices of Sydney Metropolitan areas

Source: Drawn by authors using ABS 2016 census data at SA2 level.

Besides, the lower-income residents are being excluded from the advantaged east and north of Sydney due to higher rent compared to the other parts of Sydney. Consequently, the lower-income residents are increasingly moved out from the areas with good access to jobs, transport, and services. Most of the new dwellings and population are being placed into western Sydney, which is away from natural and cultural amenities.

Disadvantaged western Sydney

Greater Western Sydney is a large metropolitan region of Greater Sydney that generally embraces the north-west, south-west, central-west, and far western sub-regions within Sydney’s metropolitan areas (Western Sydney University, 2000). It comprises thirteen local government areas of Blacktown City, Blue Mountains City, Camden Council, Campbelltown City, the City of Canterbury-Bankstown, Cumberland Council, Fairfield City, Hawkesbury City, Liverpool City, the City of Parramatta, Penrith City, The Hills Shire and Wollondilly Shire (.idcommunity, 2000).

Western Sydney contains about 9% of Australia’s population and 44% of Sydney’s population. The residents of Sydney’s west are mostly of a working-class background, with major employment in the heavy industries and vocational trade (Wikipedia, 2000). The rapid upsurge of migrant residents has enlarged the greater west’s population. Western Sydney’s population is expected to reach 3 million by 2036 and to absorb two-thirds of the population growth in the Greater Sydney – making Western Sydney region one of the largest growing urban populations in Australia (Western Sydney University, 2000).

Though the significant urban growth and development are taking place in Sydney’s west, however, the region lags in providing residents with facilities. Scheurer et al. (2017) point out that the Sydney’s most disadvantaged socio-economic groups are geographically situated in Sydney western suburbs, and the most socio-economically privileged areas are located on the east and north of Sydney, where they have walkable access to public transport while and western Sydney suburbs are highly car-dependent. Consequently, the western Sydney suburbs residents spend less time moving on foot which consequently impacts their health adversely (Roggema, 2019).

The decline of industrial employment in western Sydney suburbs and the ongoing concentration of knowledge-based employment in the east has decreased the number of jobs (or the number of secure or skills-matched jobs) that can be reached within a reasonable commuting time by the western Sydney residents (Scheurer et al., 2017). Roggema (2019) argues the low-priced housing choices are introduced in the western Sydney suburbs far from the city by converting the greenfield areas, and the new dwellings are taking place in an overcrowded form with no options of front or rear garden. Also, western Sydney has the highest records of temperature and the lowest amount of rainfall, and the tree canopy is also significantly lower comparing to the affluent north and eastern parts of Sydney (Greater Sydney Region Plan A Metropolis of Three Cities, 2018).

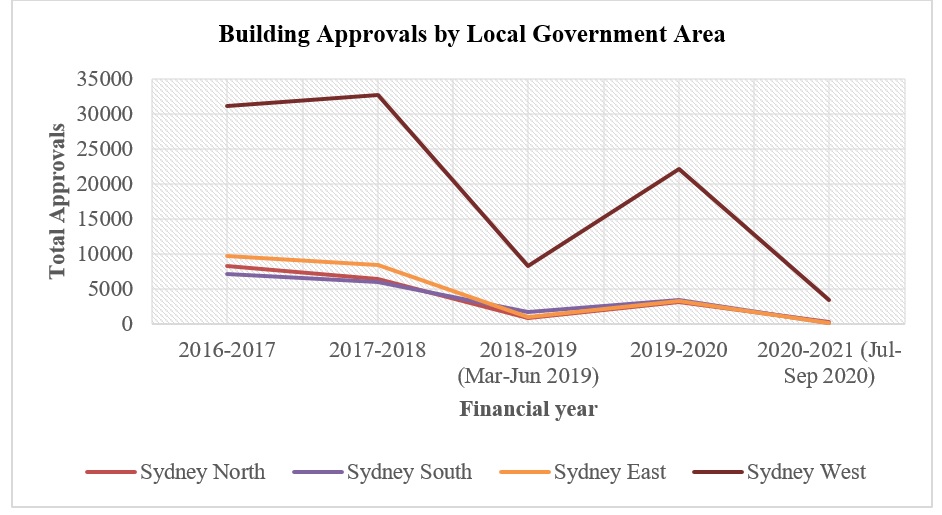

Western Sydney, uneven geography of housing destination

ABS data on the latest five financial year statistics on building approvals in Greater Sydney shows that western Sydney has been receiving most new housing. In the financial year 2016-2017, 55,995 buildings were approved in Greater Sydney. 55.44% of the approvals were in the western Sydney region. In 2017-2018 61.30%, 2018-2019 above 70%, 2019-2020 nearly 70%, and in the current 2020-2021 financial year’s July to September around 88% dwellings were approved in western Sydney local government areas.

Figure 3. Building Approvals in Greater Sydney by Local Government Area

Source: Generated by authors by using ABS data.

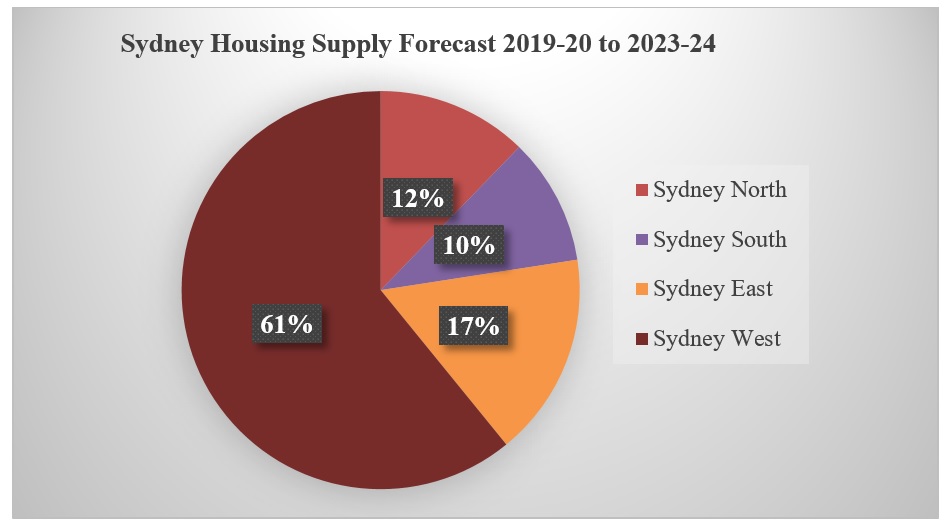

The population of Greater Sydney is anticipated to grow by 1.7 million by 2036. The NSW Government has estimated that 725,000 additional homes would be needed to accommodate the additional population (Greater Sydney Region Plan A Metropolis of Three Cities, 2018). Department of Planning, Industry and Environment (DoPI&E) is targeting western Sydney for most of the new housing. DoPI&E data clearly shows that more and more housing is being placed in the western regions compared to other parts. Greater Sydney Housing Supply Forecast 2019-20 to 2023-24 by LGAs demonstrates that 61% of the housing have been placed in western Sydney LGAs whereas the percentage for Sydney East is 17%, Sydney north is 12% and Sydney south 10%.

Figure 4. Greater Sydney Housing Supply Forecast 2019-20 to 2023-24 by LGAs

Source: Generated by authors by using DoPI & E data.

The above data shows that more and more dwellings are being built during the past years in the disadvantaged western Sydney. Overall, 61% of the new dwellings are being targeted to be built in Sydney’s west. Thus, it can be argued that due to shortages of housing in the other parts of Sydney, people are forced to live in the western region, which is thus creating locational deprivation.

Discussion and analysis focused on housing generated deprivation

Deprivation is the condition of a disadvantaged situation of a community. Residents are considered deprived if they lack the required facilities and opportunities to maintain their livelihoods. Housing location is an essential factor and an issue that affects everybody’s day to day life. Housing location disassociated with facilities and opportunities and may lead to deprivation.

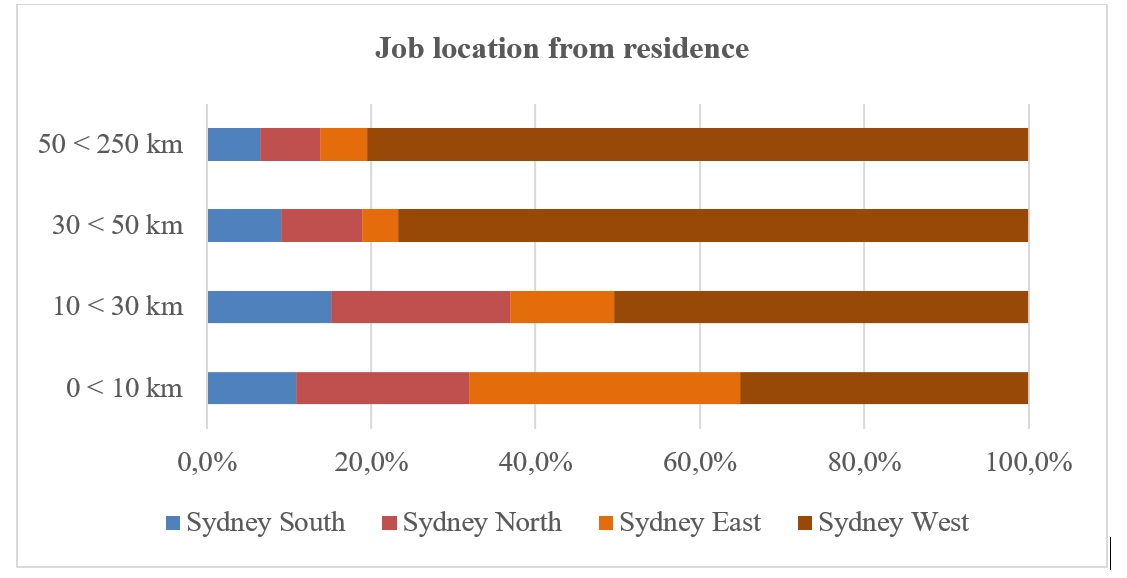

Greater Sydney has experienced a great deal of change in its hosing location due to urbanisation. As the housing supply is low and the housing price as well as rent is higher in the non-western parts of Greater Sydney, the residents of Sydney are pushed to buy or rent a house in the disadvantaged neighbourhoods, concentrated in the western Sydney. The housing locations have complex effects on the western Sydney areas residents. Figure 5 confirms that the residents who are living in dwellings located in western Sydney are facing locational disadvantage regarding job location. As people have shifted into the western suburbs, have positioned socially deprived as they are increasingly distanced from opportunities.

Figure 5. Job location from residence

Source: Generated by authors by using ABS 2016 Census data.

Housing cost either in the form of rent or mortgage payment is a key element of the household expenditures. Most of the residents in Sydney are unable to rent or buy a house in the advantaged areas. Lack of local availability of amenities is mostly affecting the residents of western Sydney. Their housing location makes good jobs, quality schools, and transport facilities inaccessible and prevents of social belongingness and vibrant lives. The far distanced location, lower quality of housing and environmental harshness has placed western Sydney residents in unfriendly and hazardous condition (Roggema, 2019, Scheurer et al., 2017). Consequently, the deprivation levels of the resident are significant in western Sydney residents.

In the COVID-19 pandemic situation, the western Sydney residents are hit hard by the pandemic induced adverse impacts. COVID-19 caused extensive job losses in Greater Sydney. Some sectors of the jobs have been hit harder than others. About 70% to 80% of western Sydney residents are engaged in non-professional and non-managerial jobs that are the that could not be done from home. The COVID-19 crisis has increased unemployment in western Sydney more than the Greater Sydney average. It is also about to surge further (openforum.com.au, 14 May 2020).

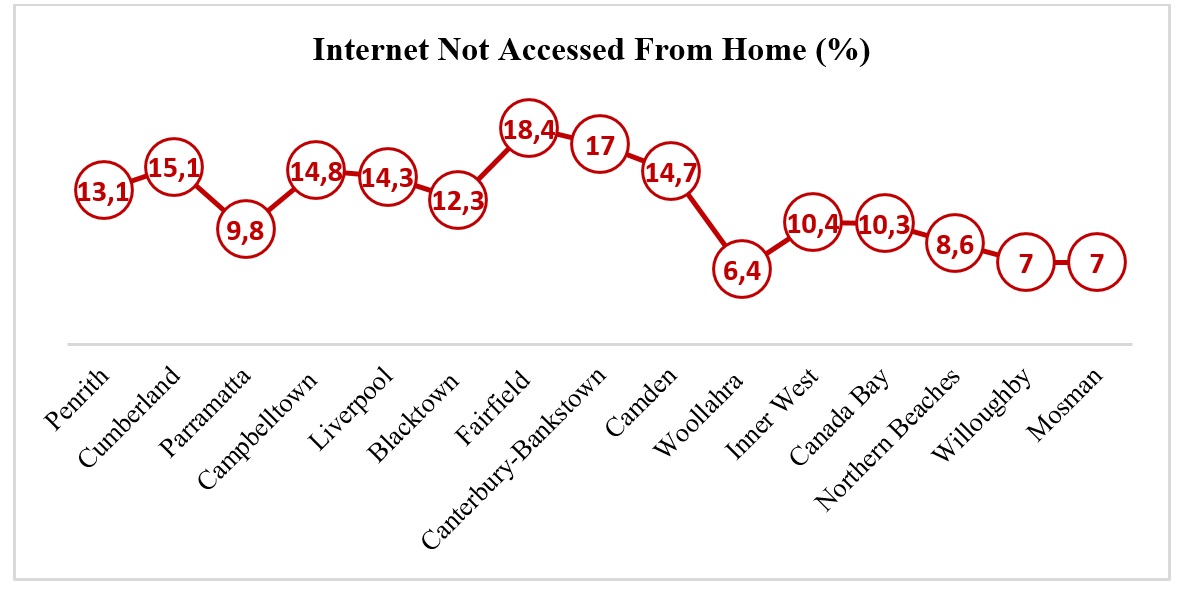

COVID-19 has pushed people to work from home, and universities also switched their classes online. However, the internet is not accessible from 10 to 20% of western Sydney houses (figure 6); besides, western Sydney residents have lack of technology skills and are involved in work which cannot be done from home (openforum.com.au, 14 May 2020). A large number of western Sydney residents were stressed working and learning from home.

Figure 6. Internet access from home in various LGAs of Sydney

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016 Census data.

Due to the job losses and end of government COVID-19 financial support, many Western Sydney areas have a higher level of poverty then-recent past. Research shows, Sydney’s north and east experience the lowest rise in poverty and eight out of the 10 Australian districts likely to face the highest surges in poverty are in Sydney’s west (The Sydney Morning Herald, 2 October 2020). Thus, the above evidence and analysis show that western Sydney residents are highly deprived and are likely to face adverse consequences due to their housing location.

Conclusion

Housing is not only an individual need; it also affects every aspect of an individual’s life. Housing location and its settings significantly influence the quality of life of individuals. Adequate urban amenities are crucial for individuals to support their lives. Considering the outcome of housing on individuals’ well-being, the adverse consequences related to housing location cannot be ignored. In order to reduce the housing location related stresses in Sydney, more housing should be built in the areas near jobs, natural and cultural amenities and transportation. Besides, governments must ensure the provision of enough education, health, welfare and employment opportunities in the disadvantaged areas to address the wider problems associated with socio-economic exclusion generated by housing location.

About the authors

Khandakar Farid Uddin is an early career academic and researcher. At present, his Doctoral PhD research at the School of Social Sciences, Western Sydney University explores urban planning policy applications, outcomes and associated inequalities in Greater Sydney. Can be reached at K.FaridUddin@westernsydney.edu.au

Dr Awais Piracha is an Associate Professor at the School of Social Science, Western Sydney University and a trained civil/environmental engineer as well as a town planner. His research and teaching experience lies in urban, environmental, transport and regional planning.

References

DUNN, J. R. & HAYES, M. V. 2000. Social inequality, population health, and housing: a study of two Vancouver neighborhoods. Social Science & Medicine, 51, 563-587.

HERBERT, D. T. 1975. Urban deprivation: definition, measurement and spatial qualities. The Geographical Journal, 362-372.

ROGGEMA, R. 2019. Contemporary Urban Design Thinking. Springer.

SCHEURER, J., CURTIS, C. & MCLEOD, S. 2017. Spatial accessibility of public transport in Australian cities: Does it relieve or entrench social and economic inequality? The Journal of Transport and Land Use, 10, 911-930.

SEN, A. 2000. Social exclusion: Concept, application, and scrutiny. Manila, Philippines: Office of Environment and Social Development, Asian Development Bank.

WONG, H. & CHAN, S. M. 2019. The impacts of housing factors on deprivation in a world city: The case of Hong Kong. Social Policy & Administration, 53, 872-888.