Grassroots Spatial Narrative Production of Chongqing: Counter-hegemony for China’s Urbanisation?

DOI reference: 10.1080/13673882.2024.12466436

By Dr Guanyu Wang, School of Geography and Planning, Cardiff University, UK.

Introduction

Although Harvey (2007) understood China’s urbanisation as a variant of neoliberalism, the new forms of cooperation between capitalism and China’s politics keep stimulating debate on whether the existing framework of urban knowledge is sufficient to understand how Chinese cities reproduce the social-political conditions to sustain their urbanisation (Wu 2020). I suggest we need a future-oriented critical perspective to engage with its emerging empirical evidence to understand and further intervene in these urban processes as well as its knowledge production instead of a mere critical reflection through Chinese urbanisation.

I focus on a unique spatial narrative production in Chongqing, the ‘Magical City’ narratives produced by grassroots social media activities, which further intervened in the urbanisation and the production of urbanity during inner-city regeneration. Chongqing, the largest city in western China, suddenly became viral on social media platforms because of its characteristic urban space shaped by super high-density construction and mountainous topography. Thus, Chongqing has been referred to as the ‘Magical City’ on social media, triggering online discussion and attracting tourists to visit and share their experiences. These spatial narratives reconstructed the urban image of Chongqing and created new ways to make sense of cities, which further influenced urban regeneration and the broader economic circulation of the city.

How may the above spatial narrative production imply a critical perspective for urban study? On the one hand, as China’s urbanisation is mainly characterised by top-down processes, this grassroots-initiated process demonstrated in the ‘Magical City’ shows a potential to challenge this ‘normalised basis’ (Herzog 2016) of Chinese urbanisation, helping to explore how democratic practices can be conceived. On the other hand, the popularity of ‘Magical City’ narratives on social media constitutes the urban transformation to a more consumption-oriented society in China embedded in hyper-consumerism, sustaining the existing state-market-society alliances and reproducing the tensions of inequality, alienation and exploitation embedded in capitalism. These potentials and tensions emerging from the dynamics between state, market, and society, as well as top-down and grassroots, imply the condition where a critical perspective may productively engage with this empirical evidence.

Urban Enquiries and Methodology

I propose two guiding urban enquires of investigation: to what extent is this grassroots production of space an alternative/critical approach to urbanisation in Chinese cities? Furthermore, how can this approach be regarded as a democratic practice for Chinese urbanisation?

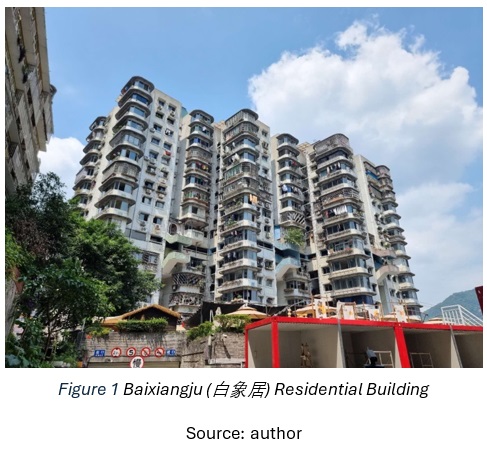

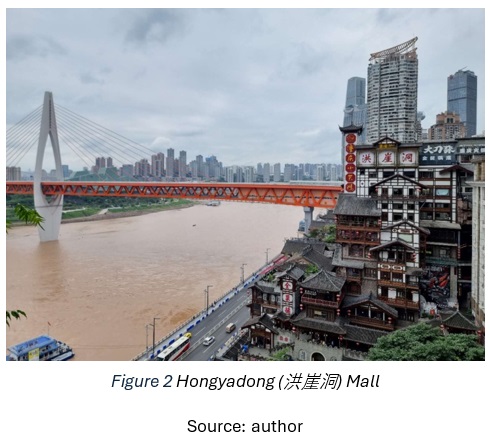

To respond to the above questions, I first sampled the ‘Magical City’ narratives by three representative spaces (figures 1, 2, 3): Baixiangju (白象居) Residential Building, Hongyadong (洪崖洞) Mall, and Liziba (李子坝) Metro Station, which were the most discussed on China’s social media. I analysed the posts communicating the above spaces on the major social media platform in China, Weibo, from 2014 to 2022 and conducted semi-participatory observations in 2022 to explore the relation between online spatial narratives and actual spatial practices taking place in the city. Then, I conducted a critical discourse analysis to explore what is communicated by the ‘Magical City’ and how to understand it within the urban context, based on which I discussed its critical potential in the context of the Gramscian construction of hegemony and broader neo-Marxist ideas.

What is Communicated by ‘Magical City’?

The most communicated within ‘Magical City’ narratives are the cityscape shaped by Chongqing’s unique spatial characters: the impressive elevation differences due to the mountainous topography, the high-density urban spaces, and the spontaneous everyday urban life in these spaces.

For example, one of the prevalent narratives is about the elevation differences discussed through the ‘bizarre’ building design that ‘a 24-storey residential building is without a lift’, which became a label of Baixiangju. While the ‘no-lift’ situation is nothing too extreme or ‘bizarre’, as the building has three entrances on different storeys linked to the nearby streets at different elevations, meaning no residents need to climb up the whole 24 storeys if they use the corresponding entrances, this fact is often overlooked by the eye-catching words focusing on the lack of lift without introducing this context.

While the ‘Magical City’ narratives originated from spatial characteristics, broader non-spatial references from contemporary pop culture have been substantially utilised for the construction of spatial narratives to enrich the meaning of ‘magical’. For example, the discussion about Hongyadong is dominated by the physical resemblance between its space and the movie scene in a well-known Japanese anime Spirited Away by Miyazaki Hayao. Posts on social media described it as a ‘fairy tale sometimes can be realised’ or ‘Miyazaki’s world does surprisingly really exist’.

Similarly, Baixiangju suddenly went viral online after being in the scene in a popular movie, Hotpot Hero, which was followed by other movies filmed there. Its unique spatial characteristics were broadcasted around China along with those movies. Apart from the movie scenes, several movie stars and fashion magazines chose Baixiangju as a place for photography, facilitating the spread of the image of this urban space. Baixiangju has been frequently mentioned together with these movies and celebrities: ‘following the movies to the hidden corner, do you remember the movie scenes of the Forest of Chongqing, Better Days… they are all hidden in this corner of Chongqing’.

The above ‘magical’ urban spaces created ‘Da Ka (打卡)’ locations around the city. ‘Da Ka’, originally meaning registering attendance at work, has gradually been used to describe the activity of recording and to show one’s visit to a place. Through tourists posting photos of visiting these urban spaces, a relatively separate narrative domain was created for sharing and inter-referencing the experience of ‘Da Ka’ beyond any particular spatial characteristics.

Another ‘magical’ characteristic of urban spaces is ‘Yan Huo Qi (烟火气)’, in other words, the sense of liveliness in the city, which is further integrated with local grassroots culture, thus creating a novel and localised notion of urban aesthetics allowing one to appreciate what is regarded as too messy and unregulated by conventional urban images. For example, in one post, what is valued most about the ‘Magical City’ is the ‘artistic, everyday urban aspect apart from its 3D topography and the warmth and coldness reflected in urban life of individuals’.

These ‘Magical City’ narratives presented fragmented themes deriving from Chongqing’s unique urban space, which was then expanded beyond the material dimension by ongoing online narrative construction. The ‘Magical’ of the city has been developed from its material base to an individual sphere of meaning creation, where a new urbanity was created on how urban life can take place in Chongqing’s ‘Magical City’ environment. In other words, ‘Magical City’ was instrumentalised as an empty signifier emancipated from the material domain to relate these spatial characteristics with various references from pop culture, everyday urban life and personal urban experience to help sense, make sense of and communicate the city based on their impressiveness and novelty for wider online dissemination and tourist urban lifestyle.

‘Magical City’ as Hegemonic Project

How does the popularity of the ‘Magical City’ narratives help enlighten any critical perspective? If ‘Magical City’ is more of an empty signifier that is fragmented and fluid, how can we explore its critical potential? I suggest that the construction of ‘Magical City’ narratives is a hegemonic project, and understanding its counter-hegemonic dimensions implies the critical potential to use this grassroots production to conceive democratic practices in China’s urbanisation.

Proposed by Gramsci (1971), hegemony is a concept to understand how a social group seeks power through intellectual and moral leadership with a combination of coercion and persuasion instead of simple enforcement. While hegemony indicates a state of dominance, it also refers to a process of power struggles where counter-hegemony must operate simultaneously. This notion implies that all ‘political concentrations, centres, fixed points, relations alignments are always contingent, always partial, always temporary and always contested’ (Purcell 2009, p. 295).

Therefore, understanding the ‘Magical City’ construction as a hegemonic project helps to politicise this urban process, revealing the power dynamics in tension where these grassroots narratives intervene to maintain or struggle against China’s hegemonic urbanisation shaped by neoliberalism and authoritarianism. This politicisation is a tool not only to deconstruct the status quo but also to depart from it. Thus, the ‘Magical City’ does not only refer to those spatial characteristics. Instead, it refers to those specific approaches in which spatial narratives narrated the elevation differences through telling the story of ‘no lift’ or represented high-density living environments through popular movies and songs. It indicates the political dimension of spatial narratives seeking the social consensus on certain values of the visual impressiveness of urban space by signifying specific spatial characteristics while excluding others from constructing Chongqing’s urban images.

While the ‘Magical City’ narrative construction appears as an agential practice from the grassroots seeking for the leadership of how the city is sensed and made sense of, the hegemonic dimension also implies its structural aspect (Joseph 2000) that conditions the exercise of a hegemonic project. More specifically, the ‘Magical City’ constitutes the ongoing urban transformation in China. On the one hand, those previously lost spaces in the city, socially deprived or abandoned, have been revitalised with lively urban life, though tourists-dominated, and started to attract investment and financial resources. On the other hand, the state and developers then actively participated in initiating formal urban regeneration, producing more spaces that resemble these grassroots spatial representations to facilitate tourism. These top-down produced urban spaces induced by the existing grassroots ‘magical’ spaces usually inherited the spatial features of the ‘magical’ as the expanded service area for those tourist attractions to accommodate amenities and services such as cafeterias, hotels and restaurants, bringing gentrification and social stratification along with the economic prosperity. This depicts the condition of this hegemonic project where ‘Magical City’ fits into the broader urban transformation to a more consumption-oriented urbanisation and constitutes a part of its new urbanity, further sustaining the existing state-market-society alliance in China’s urban authoritarian capitalism and its urban economic circulation.

Counter-hegemony and Democratic practices

If the ‘Magical City’ fits comfortably within the existing Chinese urbanisation, then to what extent is it counter-hegemonic? First, the everyday urban perspective dominating the narratives is pivotal in realising its counter-hegemonic potential by breaking the link between the construction of urban image and top-down planning in China. It challenged the state’s monopoly in the interpretation and representation of the urban. Meanwhile, this perspective created spatial representations, both verbal and imagery, which were more accessible to comprehend for the public than any other official representations of the city, which consequently invited the public to participate in the narrative construction, maintaining the hegemonic project to generate more narratives from various personal perspectives. Additionally, this perspective helped to appreciate the city’s marginal and underground corners by advocating urban narratives revealing and broadcasting the imperfection and messiness of urban life, thus leading to an urban aesthetic in contrast to the urban space produced by formal planning in China.

Unpacking this embedded everyday urban perspective shows that the exercise of this counter-hegemony project was restrained, shaping its characteristics and potential with the intrinsic power imbalance long embedded in China’s urbanisation. For example. the everyday perspective prevailing in ‘Magical City’ narratives is highly tourist-focused, while other groups of people are excluded. Although it encouraged the authenticity of urban representations in contrast to the official propaganda and state-dominated urban images, the authenticity created by this highly exclusive definition of everyday life perspective was tailored mainly for consumption rather than the diverse social and political dimensions of urban life, risking alienating urban space. Thus, the counter-hegemony is intrinsically class-biased and counter in a non-Marxist way.

While the grassroots-born urban aesthetics symbolised some narrative representations of democratic urban processes, the ‘Magical City’ also organised democratic practices based on people’s shared urban experiences and imagination, challenging the authority’s urban narratives. For example, there emerged further grassroots online movements re-imagining other cities by collaging the real scenes with different imagined surrealist ‘Magical City’ spaces. These practices represented playful interactions of the public enquiring and making fun of the formal urban transformation, symbolising a degree of indifference and disobedience to top-down planning.

Following the more recent interpretation of hegemony, for which counter-hegemony is understood as the deconstruction of hegemonic articulation and the forming of unified frontline (Laclau and Mouffe 2001), these democratic practices imply critical potential beyond the orthodox Marxist critique of capitalism. For example, the ‘Magical City’ narratives deconstructed the state’s monopolistic control to produce urban images, meanwhile contributing to the reproduction of capitalism by hyper-commercialising urban space and its representation using social media platforms. It is overly simplistic to see these urban processes as mere complicity of neoliberalism, as the struggles within the capitalist framework can still help to struggle against the authoritarian regime strategically, thus intervening in the power dynamics of state-market-society which reproduces capitalism and authoritarianism in China.

Conclusion

‘Magical City’ was constructed around the exaggerated narratives of the perceived urban space by different individuals describing Chongqing’s spatial characteristics. While deriving from certain spatial characteristics of Chongqing, ‘Magical’ was instrumentalised as an empty signifier to relate the spatial characteristics with various references from pop culture, thus shaping the ways in which people sense and make sense of urban spaces. When we understand ‘Magical City’ as a hegemonic project, it challenges the authority’s top-down urban narratives by proposing an everyday perspective to appreciate the messy and unregulated. However, these counter-hegemonic spaces were then gradually subsumed under the framework of the state-market-society alliance, meanwhile can still be seen as democratic practices for intervening in the power dynamics within this alliance.

As these democratic practices are class unconscious, thus hardly critical in the conventional Marxist sense, it may help to reflect on what counter-hegemony can be in a post-neoliberal age for global urban study. As China’s urbanisation trajectory is somehow unique while still substantially involved in neoliberal globalisation, I suggest ‘China as a method’ (Shin et al. 2022) for global urban study to explore its critical potential. On the one hand, China’s urbanisation is a method to sustain its unique political dynamic, or in other words, the so-called ‘urban with Chinese characteristics’ (Hamnett 2020). On the other hand, the globalisation of China’s urbanism, with its rising influence shaping global capitalism and probably the rise of authoritarianism, is a methodological invitation for critical engagement from the global urban study. ‘Magical City’ provides a starting point for urban critiques to engage with how democratic practices can be interpreted in authoritarianism and how spatial production can mutate, compromise and utilise these political practices to empower as well as endanger the critical potential embedded in China’s urbanisation, thus generating a domain of hegemonic and counter-hegemonic struggles of urbanisation as well as the production of its knowledge.

References

Gramsci, A. 1971. Selections from the prison notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Hamnett, C. 2020. Is Chinese urbanisation unique? Urban studies (Edinburgh, Scotland) 57(3), pp. 690-700. doi: 10.1177/0042098019890810

Harvey, D. 2007. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford: Oxford University Press, Incorporated.

Herzog, B. 2016. Discourse analysis as social critique : discursive and non-discursive realities in critical social research. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Laclau, E. and Mouffe, C. 2001. Hegemony and socialist strategy : towards a radical democratic politics. 2nd ed. London: Verso.

Purcell, M. 2009. Hegemony and Difference in Political Movements: Articulating Networks of Equivalence. New Political Science 31(3), pp. 291-317. doi: 10.1080/07393140903105959

Shin, H. B., Zhao, Y. and Koh, S. Y. 2022. The urbanising dynamics of global China: speculation, articulation, and translation in global capitalism. Urban Geography 43(10), pp. 1457-1468. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2022.2141491

Wu, F. 2020. Adding new narratives to the urban imagination: An introduction to ‘New directions of urban studies in China’. Urban Studies 57(3), pp. 459-472. doi: 10.1177/0042098019898137