Governance of regional development: How can regions unlock their potential?

DOI reference: 10.1080/13673882.2018.00001040

By Yasmine Willi and Marco Pütz (Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research WSL)

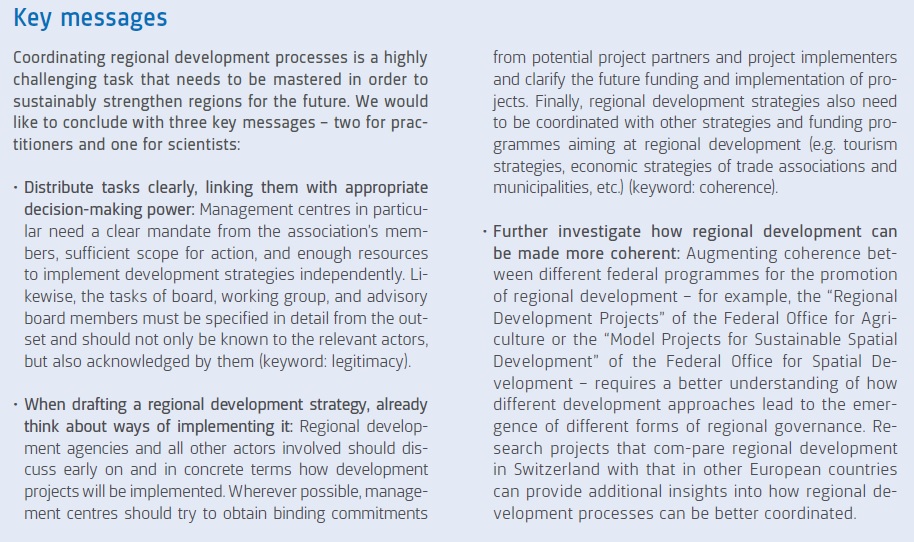

Regional development is a mainstay of Swiss domestic policy, as evidenced by the federal government’s New Regional Policy, regional nature parks, and more. But how do regional development processes really work? And how could they be more effectively supported? This factsheet analyses existing models and provides recommendations for action.

This article was first published as Willi Y, Pütz M (2018) Governance of regional development: How can regions unlock their potential? Swiss Academies Factsheets 13 (3) It can also be downloaded in French and German.

Regional governance is often seen as an instrument to foster collaboration between municipalities, improve regional development processes, and make a region more competitive (OECD, 2006; Meadowcroft, 2007). In addition, regional governance is also recognized as an analytical concept that can be used to investigate the workings of regional development processes (Pütz et al., 2017). In this factsheet, regional governance refers to a concept that describes how public and private actors who represent the diverse interests of public authorities, the private sector, and civil society coordinate regional development processes (Willi et al. 2018).

This factsheet is based on a doctoral dissertation about “Governance of Regional Development” written at the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research WSL that, amongst other things, analyses how regional development agencies in Switzerland formulate and implement regional development strategies. The dissertation focuses on regional nature parks, which implement the parks policy of the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN, 2014), as well as on associations of municipalities aligned with the New Regional Policy of the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO, 2017).

Regional development agencies are key

Over the past decade, various regional development agencies in Switzerland have been newly founded or restructured to function as key regional actors and take over tasks of regional development. This process has mainly been driven by new approaches in the federal government’s regional policy. The creation or amendment of federal laws and funding programmes – for example, the amendment of the Federal Act on the Protection of Nature and Cultural Heritage (2007) or the introduction of the Federal Act on Regional Policy (2006) – has strengthened the role of regions, a trend that has been observed in other European countries as well (OECD, 2016). Municipalities and cantons are also increasingly recognizing the potential of regional cooperation (cf. Inderbitzin and Hauser, 2016). Being tasked with the coordination of regional development processes, regional development agencies have a key role in regional governance. Regional development agencies in Switzerland are organized either as public sector corporations (e.g. “regions” in the Canton of Grisons or “regional conferences” in the Canton of Bern), as stock corporations (e.g. Region Oberwallis AG), or as associations. The majority of regional development agencies are organized as associations, which is why the following analysis focuses on this legal form of organization.

Regional development agencies that are organized as associations have no politically authorized power and therefore depend strongly on their members (in addition to the criteria of the relevant funding programmes). They may have an“exclusive” membership, consisting entirely of public entities (usually municipalities), or an “inclusive” membership, comprising both public and private entities (e.g. interest groups, local businesses, local inhabitants, and guests). Regional development agencies with an exclusive membership often involve private actors by appointing them as advisers to the board or inviting them to participate in working groups. However, regardless of whether they have formal membership or not, private actors largely remain providers of ideas and input. The municipalities have a majority of votes both in the board and in the general assembly and can thus significantly influence decision-making.

Development strategies bring actors together

Regional development strategies help to initiate and coordinate development processes in a targeted way. In Switzerland, regional development strategies include, among others, the four-year plans of regional nature parks and the strategies of regional associations of municipalities aligned with the federal government’s New Regional Policy.

Funding programmes, the legal framework, and other federal, cantonal, and municipal guidelines provide the basis for formulation of a regional development strategy. In addition, such a strategy usually incorporates contributions from regional actors that the management centre solicits by means of informational events, workshops, and expert consultations. The strategy is normally conceived and formulated by the management centre, often in close collaboration with the board, and is then presented to the general assembly for approval. The process of strategy development is time-consuming and demanding, but at the same time it helps to build and consolidate a shared understanding of the region’s development goals among diverse regional actors.

The overall design of a regional development strategy depends, among other things, on the guidelines of the relevant funding programme. Regional nature parks are required to structure their four-year plans according to the relevant federal guidelines, whereas most associations of municipalities implementing the New Regional Policy are free to choose the level of detail with which they wish to formulate their strategies. Detailed regional development strategies usually include comprehensive project descriptions with detailed lists of objectives, implementing organizations, and budgets. Drafting a detailed regional development strategy is time-consuming and resource-intensive, as multiple actors contribute to the process, participate in decision-making, and have to find a consensus regarding objectives, measures, projects, and budgets. However, once approved, a detailed development strategy is to a large extent binding and gives the regional development agency scope for action by clearly allocating responsibilities and tasks.

By contrast, many regional development agencies – especially associations of municipalities implementing the New Regional Policy – have broadly formulated regional development strategies (cf. Inderbitzin and Hauser, 2016). Such strategies are largely limited to general goals and non-binding visions. They frequently lack both a concrete time frame and clearly formulated measures for action. Projects are either only roughly outlined or not described at all. Broadly worded development strategies are often readily and rapidly approved, precisely because they describe approaches in general terms (e.g. “Promote the region’s competitiveness”), remain non-binding, and leave many – potentially conflictual – matters (e.g. project funding or questions of responsibilities) unresolved. However, the general nature of the goals formulated, their non-binding character, and the lack of concrete measures for action can make such strategies difficult to implement.

International brands dominate advertising. What do we need to improve the marketing of regional products? (Photo: Gero Nischik)

Regional development strategies require support

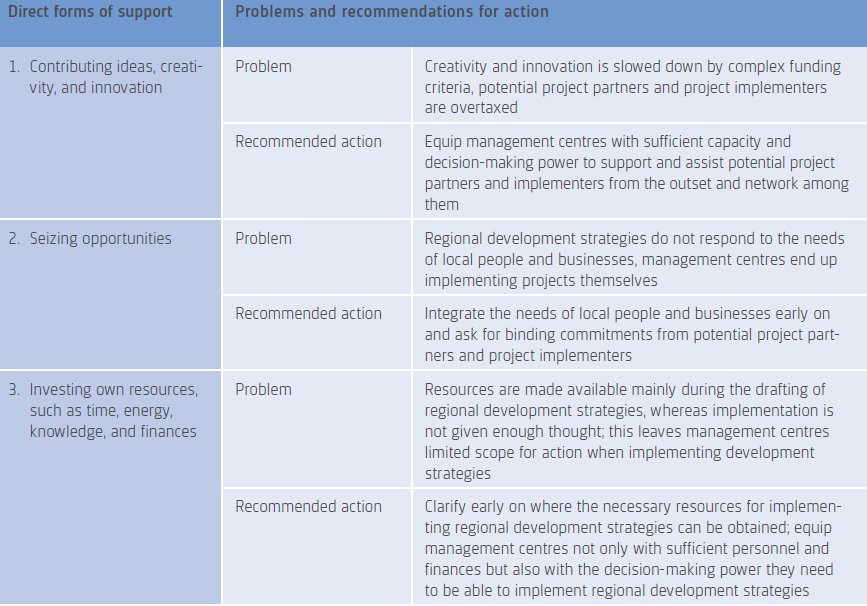

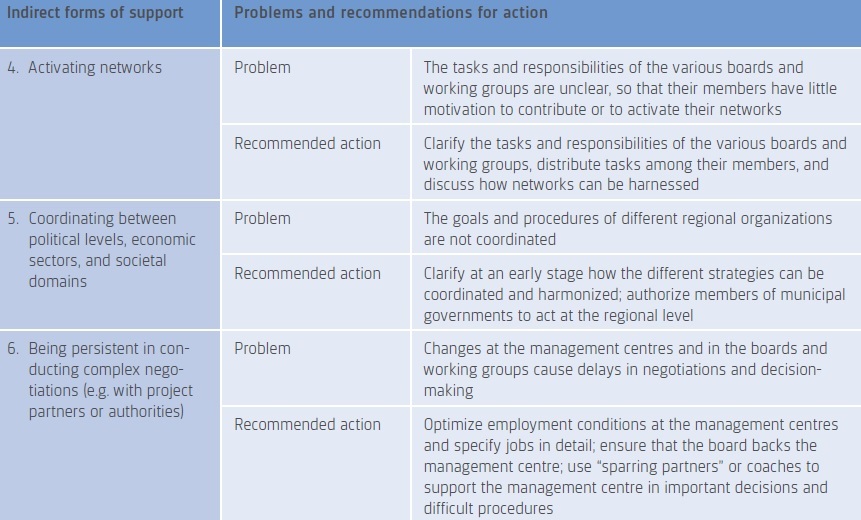

The implementation of regional development strategies – and hence the outcomes of regional development processes – strongly depend on support from regional actors. Based on the concept of policy entrepreneurs (e.g. Kingdon, 2011), we distinguish between direct and indirect support and identify three concrete ways each in which regional actors can support regional development processes (see infobox on next page).

In practice, direct and indirect forms of support are not always clearly distinguishable, as regional actors often support regional development processes with a combination of the above activities. Although indirect support is more often provided during strategy development and direct support during implementation, both types of support are important throughout the entire regional development process. In the following, based on 33 interviews with experts from six Swiss regional development agencies, we describe a number of problems that can arise in connection with the above forms of direct and indirect support from regional actors during implementation of regional development strategies. At the same time, we derive practical recommendations on how to avoid these problems and achieve better coordination of regional development processes.

First, the funding programmes’ partly complex guidelines slow down the innovativeness and creativity of potential project partners and implementers and prevent them from concretizing project ideas. It can happen that funds available for initiating regional development projects are not fully used because the complexity of project submission scares off potential project partners and implementers:

“When you find someone [who has an idea], the next problem is the question of how you implement it. Because, at that point, things become complicated, with all the application procedures and frameworks prescribing this and that. Then they quickly say: I’m certainly not interested in writing some long report.” Mayor and board member

It is therefore important that management centres of regional development agencies have the necessary capacities and authority to support and advise potential project partners from the outset. Funding criteria should provide some room for manoeuvre and scope for handling project proposals unbureaucratically. Further, it helps if management centres take over administrative tasks during project development, such as organizing meetings among the relevant actors. This likewise requires a certain amount of resources.

Second, some of the project ideas formulated in regional development strategies are not sufficiently geared to the needs of local businesses (cf. Crevoisier et al., 2011). As a result, local businesses do not see these projects as opportunities, and this makes it difficult for management centres to find appropriate private-sector support when it comes to implementation. Instead, they are often forced to invest a disproportionate amount of time and resources to get such projects off the ground. And to prevent them from being abandoned, the management centres themselves often assume responsibility for project implementation, which further burdens their limited capacities:

“Experience shows that it takes an incredible amount of time and resources [to develop a project]. And if we [the management centre] don’t buckle down, things don’t progress. […] It is possible to eventually make a difference, but it takes resources and someone who keeps things going.” Director of management centre

To avoid such situations, it is crucial that management centres work together closely with actors from the outset of regional development strategy drafting, and that actors not only contribute ideas, but also show interest in actively supporting and implementing future projects. Wherever possible, management centres should try to obtain binding commitments from potential project partners and project implementers already during the process of strategy development.

The “Holzweg Thal” (“Thal Wood Trail”) was initiated by wood processing businesses based in the Thal Nature Park. Today, they run the project jointly with Region Thal, several municipalities and citizens’ communities, the local forest owners’ association, and the Thal forest service. (Photo: Thal Nature Park)

Third, regional development strategies are often prepared without sufficient thought given to their future implementation. While large amounts of time, energy, knowledge, and finances flow into strategy development (e.g. to organize multiple-day workshops or produce high-quality print material), regional actors are often not willing to invest a similar amount of own resources into implementation. At the same time, management centres often lack the official decision- making power they would need to be able to implement regional development strategies independently. Management centres have limited scope for action to fulfil the expectations of municipalities, businesses, and inhabitants:

“Here in our region there is a strong expectation that we should promote economic development. But we actually don’t even have a mandate from the municipalities. […]. The municipalities would have to give us money for that, and a proper mandate.” Director of management centre

This means that questions of how the necessary resources for implementation will be obtained and which actors are willing to invest in future projects need to be discussed already during strategy development. Moreover, along with sufficient personnel and finances, management centres of regional development agencies also need a formal mandate and official decision-making power if they are to implement development strategies independently.

Fourth, regional actors who are members of the board, of working groups, or of advisory boards quickly lose their motivation to work for these bodies if their task is not clearly defined. Uncertainty causes regional actors to feel disregarded, and if the situation of vagueness persists, they are likely to switch to obstructive behaviour:

“Every time the working group […] meets, one quarter [of the members] don’t show. And those who do show were absent last time and call everything into question. […] To change this, we would need a mandate from the board. But they are busy with their own work.” Working group member

It is therefore important that the tasks of members in the various boards and committees are clarified early on, and that responsibilities are documented. Who has which decision- making power must likewise be clarified. The significance of a clearly formulated mandate should not be underestimated.

Regional development agencies face diverse expectations. Is it possible to find a common pathway? (Photo: Gero Nischik)

Fifth, regional development strategies are difficult to implement if they are not sufficiently coordinated with the (development) strategies and activities of other regional organizations (e.g. trade associations and tourism associations). In such cases, instead of complementing each other, the various regional organizations may get in each other’s way. For this reason, the various regional (development) strategies need to be coordinated and harmonized early on, and ways of dealing with overlaps and potential conflicts should be discussed and clarified. Further, it makes sense to explicitly authorize members of municipal governments to act at the regional level:

“In our municipality, we have a legislative programme [which states, among other things,] that we want to actively participate in regional initiatives. This is important, because we could also simply be a member without participating actively. With this legislative programme, I have the explicit permission of my colleagues [from the municipal government] to be actively engaged.” Mayor and vice-president of regional development agency

Sixth, frequent changes of personnel at the management centres, but also in the associations’ boards and committees – for example, as a result of municipal elections – interrupt and delay development processes. At the same time, changes in the people involved can also enable new developments, if new actors bring along new momentum. Some changes, for example in municipal governments or in trade associations, are “natural” and cannot be avoided. By contrast, changes of personnel at management centres can be reduced by optimizing the working conditions and equipping the centres with sufficient official decision-making power and clearly defined mandates. Moreover, a board that backs its management centre explicitly and publicly is crucial to a supportive political environment and increases the management centre’s ability to initiate change. Last but not least, external “sparring partners” (peers, mentors, or coaches) can support management centres in important decisions and difficult procedures:

“Being the manager [of a regional development agency] is a lonely job. They always have to be operational and do justice to all partners and stakeholder groups, and if the agency doesn’t have a strong president who is really present and engaged, managing directors are left very much to their own resources. […]. And in such situations it helps to have someone external to talk to.” Consultant

Recommendations for action

The following table summarizes the problems that can arise during implementation of regional development strategies and proposes ways of addressing them, based on our insights from six Swiss regional development agencies.

About this Factsheet

This factsheet is based on the doctoral dissertation entitled ‘Governance of Regional Development’ by Dr. Yasmine Willi under the supervision of Dr. Marco Pütz at the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research WSL (2014—2018). The project has been financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation.

References

Crevoisier O, Jeannerat H, Scherer R, Zumbusch K (2011) Neue Regionalpolitik und privatwirtschaftliche Initiative. Staatssekretariat für Wirtschaft SECO, Bern.

FOEN (2014) Handbuch für die Errichtung und den Betrieb von Pärken von nationaler Bedeutung. Mitteilung des BAFU als Vollzugsbehörde an Gesuchsteller. Federal Office for the Environment FOEN, Bern, Switzerland; available in G, F, and I at

Inderbitzin J, Hauser C (2016) Regionalentwicklung– Management auf einer Zwischenebene, in Bergmann A, Giauque D, Kettiger D, Lienhard A, Nagel E, Ritz A, Steiner R. Public Management. Weka Verlag, Zurich, Switzerland, pp 915–943.

Jordan A (2008) The governance of sustainable development: Taking stock and looking forwards. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 26(1):17–33.

Kingdon J (2011) Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies. 2nd edition. Longman, Boston, MA, USA. Meadowcroft J (2007) Who is in charge here? Governance for sustainable development in a complex world. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 9(3–4):299–314.

OECD (2006) The New Rural Paradigm: Policies and Governance. OECD Publishing, Paris, France.

OECD (2016) OECD Regional Outlook 2016: Productive Regions for Inclusive Societies. OECD Publishing, Paris, France.

Pütz M, Gubler L, Willi Y (2017) New governance of protected areas: Regional nature parks in Switzerland. eco.mont 9 (Special Issue):75–84.

SECO (2017) The New Regional Policy of the Federal Government. Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research EAER and State Secretariat for Economic Affairs SECO, Bern, Switzerland.

Willi Y, Pütz M, Müller M (2018) Towards a versatile and multidimensional framework to analyse regional governance. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 36(5) 775–795.