The Role of Gender in Effects of Labor Market Status on Subjective Wellbeing across European Welfare Regimes

DOI reference: 10.1080/13673882.2018.00001027

By Judit Kalman Ph.D., Center for Economic and Regional Studies, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Hungary

In this Regional Insights article, Judit Kalman, as part of her Regional Studies Association Membership Research Grant Scheme (MeRSA), investigates what determines gender differences in subjective wellbeing across old and new EU member states and also across different welfare regimes. Judit concludes that there are a great variety of institutions, policies and macroeconomic, as well as social contexts, across Europe that affects differences in wellbeing. Her research confirms welfare and gender regime typology, as well as the finer measure of generosity of welfare provisions, to matter; as these not only affect individual decisions on labor market participation, education and fertility (many of which are desired policy goals) or outcomes, like subjective wellbeing, but also socioeconomic processes and even gender norms in the long run.

Introduction

By now there is ample (academic and policy) evidence that human capital is crucial for an inclusive growth and regional development. It is increasingly recognized by policymakers too, as shown by its importance in European Union (EU) policies such as the EU2020 goals and Cohesion policy, amongst others. In exercises of measuring progress in quality of life, subjective evaluations are also getting more and more attention besides the measurements based on GDP statistics. Subjective well-being is a complex concept; while it is recognized that inequalities in well-being are not only related to social–spatial issues, be it at a macro-region, country or regional level (e.g. Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi report, 2009, OECD How’s Life in your region series), but they are also very important for resilience and several societal outcomes too.

Economic crisis and austerity programs brought an increase in relative income poverty for many, a decrease in life satisfaction (especially in Southern Europe) and huge changes in welfare, family benefits and active labour market programs, amongst others. It is the welfare state policies however, that can trigger or smooth negative effects of unemployment, inactivity and poverty on subjective wellbeing, health and several other outcomes – especially for vulnerable groups.

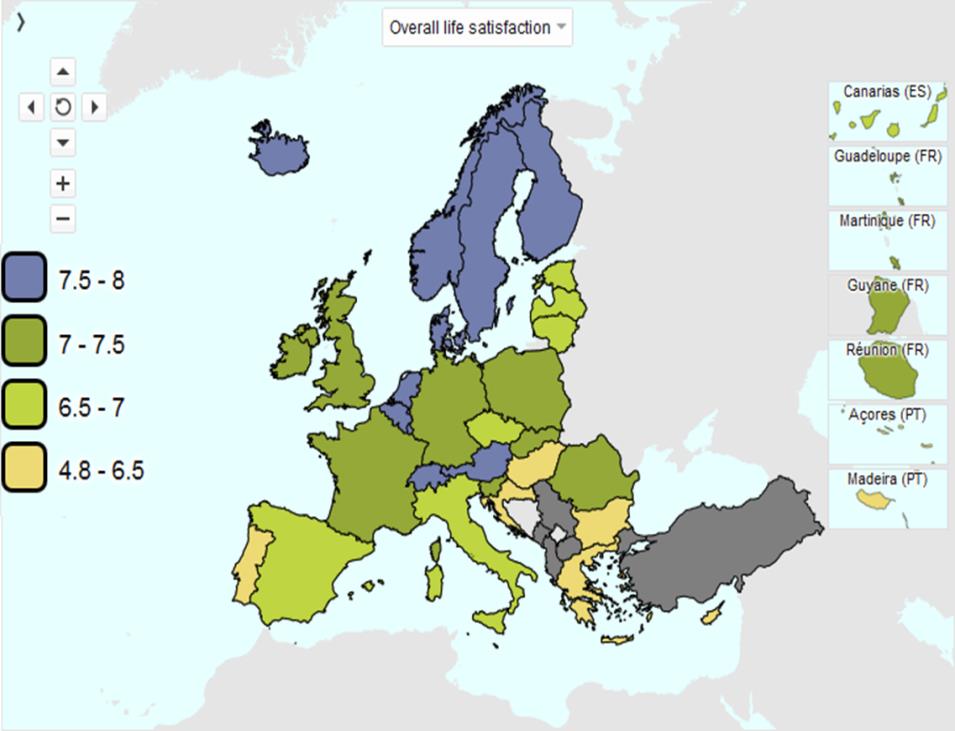

Figure 1. Life satisfaction across Europe 2013.

Source: Eurostat

The puzzling gender gap in happiness

In high-income countries, women report a higher level of life satisfaction than men, but score lower on short-term positive and negative emotions and suffer from higher levels of depression. This positive gender gap in happiness is a puzzle (Kahneman and Kruger 2006, Clark and Senik 2010, Boarini et al. 2012,Senik 2016). Women have several objective reasons to be less satisfied with their life and their jobs, through persistent disadvantages in the labour market (lower wages, more part-time, glass-ceilings, see Eurofound 2016); yet there might also be effects through age, education, income, difference in aspiration, time-use, parenthood and other life-cycle events or different institutions, family and work patterns and gender norms across countries. Different female labor market participation, work-life balance, job insecurity, informal and unpaid work are major issues worldwide and among the EU goals, with different policy answers across countries; however, we know little about how these policy answers affect gender differences in wellbeing across different welfare state regimes.

Institutions matter even in subjective wellbeing

As for individual and societal determinants of subjective wellbeing (SWB, e.g. Dolan et al. 2008 offer a good review) identification and establishment of causal relationships is not easy due to imperfect data. Life satisfaction is usually higher for those with higher income(e.g. Clark et al. 2008, Clark &Lelkes, 2005 etc.), for the more educated, for married; in contrast is lower for the unemployed (Easterlin 2001, McKee-Ryan et al. 2005). The negative effect of unemployment is stronger than that of certain other life events, like divorce or loss of income (Frey-Stutzer 2002).

Across countries, people living in richer regions, often characterized by higher GDP, tend to have higher levels of SWB (Alesina et al. 2004, Easterlin et.al.2010). Researchers have identified trade-offs between inflation and aggregate unemployment (Di Tella et al. 2001, Di Tella et al. 2003), job security in public vs. private sectors, and the importance of social norms and adaptation techniques (Clark 2003, Stutzer_Lalive, 2010, Clark 2009 etc.). Importance of social context (Helliwell 2003, Helliwell et al. 2009) and social capital (Rodriguez-Pose-Berlepsch 2012) or the role of political institutions (Frey-Stutzer 2000)and inequalities within societies (OECD 2015) are also emphasized. Alesina et al. (2004) has indicated the strong role of institutions in differences of factors driving the happiness of Americans and Europeans – an approach my research applies along different welfare state regimes, whilst Boye (2011), for example, showed that those European countries whose institutions encourage the dual-earner model of the household, are also where both women and men report the highest level of subjective wellbeing. Moreover Senik(2016), Cooke (2006), Korpi(2000), Sjöberg(2004), Nieuwenhuis et al. (2012)suggest that institutions also shape gender norms within a country.

Country-/state specificities, in especially labor market, and welfare policies are important as they can trigger or smooth effects of unemployment/inactivity/poverty etc. – especially for vulnerable groups, for whom it may cause lasting effects on wage, re-employment, health or SWB. Such social protection is supposed to increase wellbeing of citizens– but the welfare state received relatively little attention in the SWB literature (Veenhoven, 2000; Ott, 2010; Bjrornskov et al. 2007). Using data from waves 1-7 of the European Social Survey (ESS) and doing pooled cross-section analyses, my research contributes by focusing on welfare regimes, the generosity of welfare policies and extends the approach of Pacek and Radcliff (2008) and Veenhoven (2000) in using the comprehensive welfare state measure of Scruggs (2014) and adding the gender aspect.

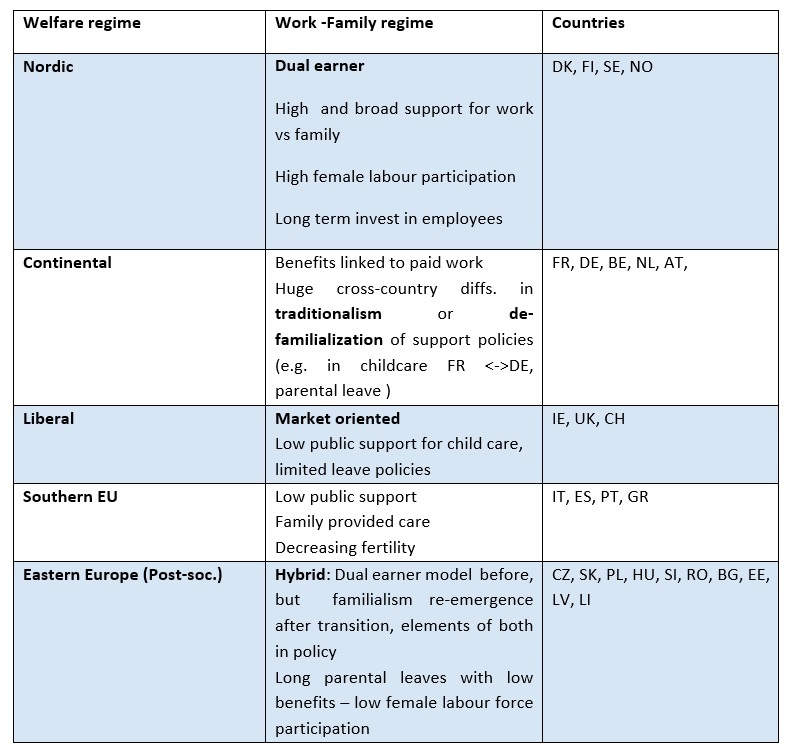

There exists broad regional or cultural country groupings of life satisfaction – which can be cut along several typologies. The welfare regime typology (extended since Esping-Andersen) and the VOC literature is just one, however widely used – although like all typologies, provides a somewhat crude grouping with always a few questionable cases or outliers. If we try to connect it (Table 1 ) with the vast literature on work-family regimes (Korpi 2000; Korpi et al 2013), and that on gender regimes ( Meyers-Gornick, 1999; Gornick-Meyers 2003, etc.), the picture gets even more complicated, but still a useful starting point.

Table 1. Welfare and work-family regimes across Europe

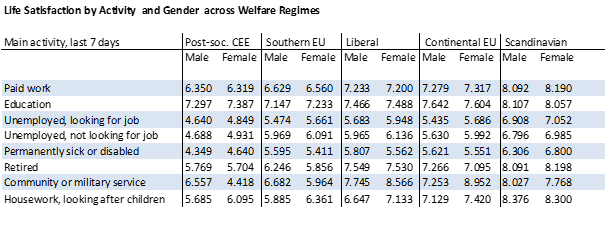

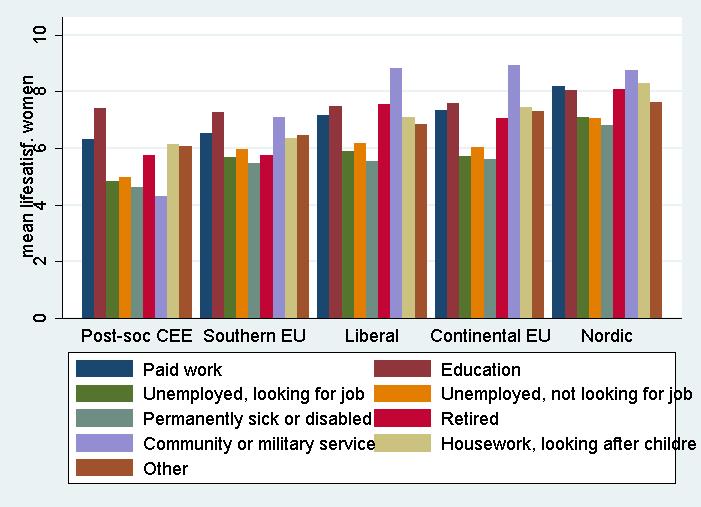

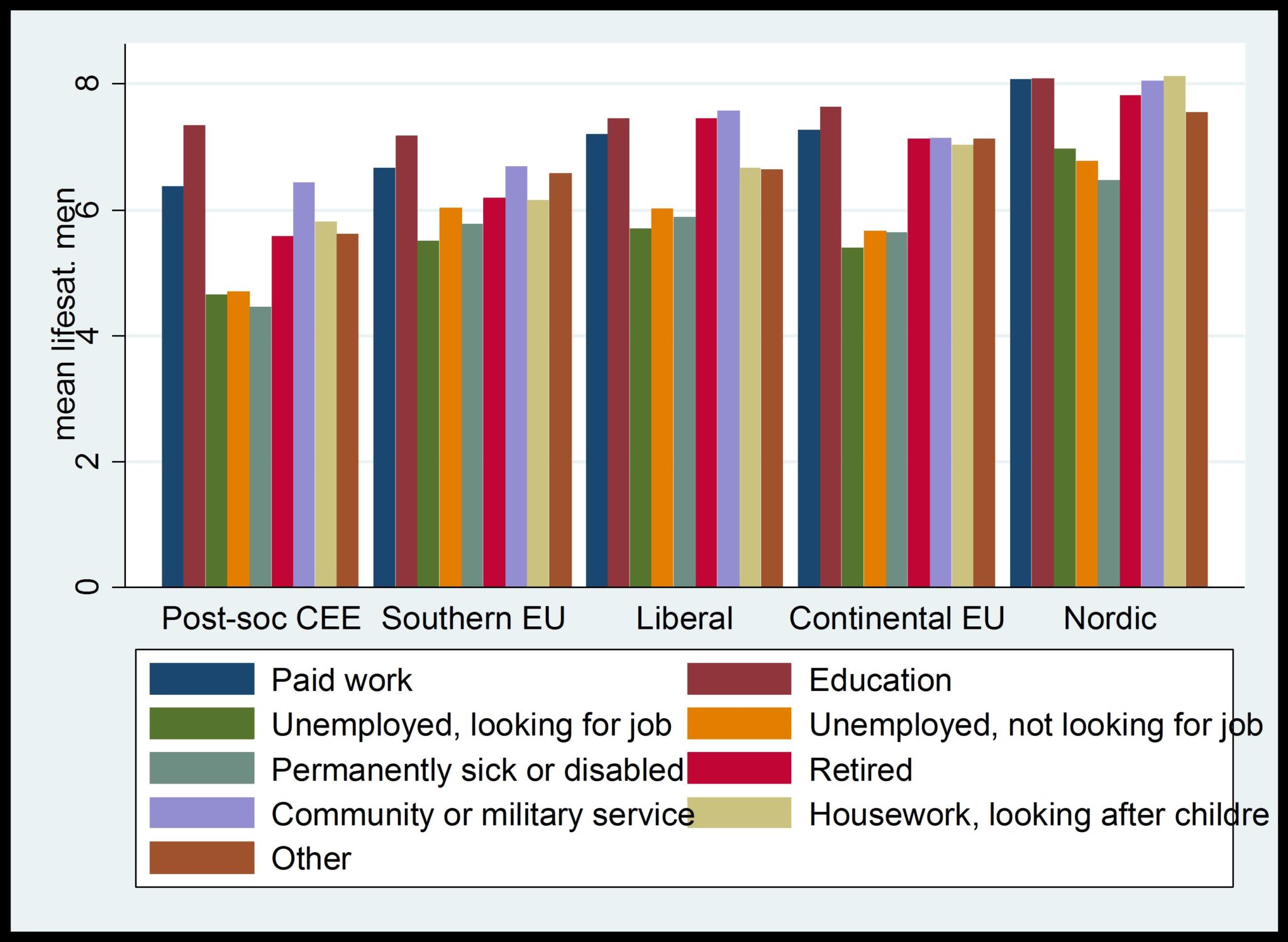

Life satisfaction across welfare regimes – Although European welfare states differ widely in their approaches and policies, using these typologies one can easily infer some of the main relationships. It is visible, that in general subjective wellbeing is lowest (Table 2, Figure 2 and Figure 3) in the post-socialist Eastern and Southern European countries, even among those with paid employment, but especially among the unemployed or disabled – who are more dependent on welfare benefits. Already from these means it is clear – also confirmed by multivariate analysis results not shown here – that unemployment has more negative effects on men than women across all welfare regimes.

Table 2.

Figure.2 Mean life satisfaction of women and men by activity status across welfare regimes

Women

Men

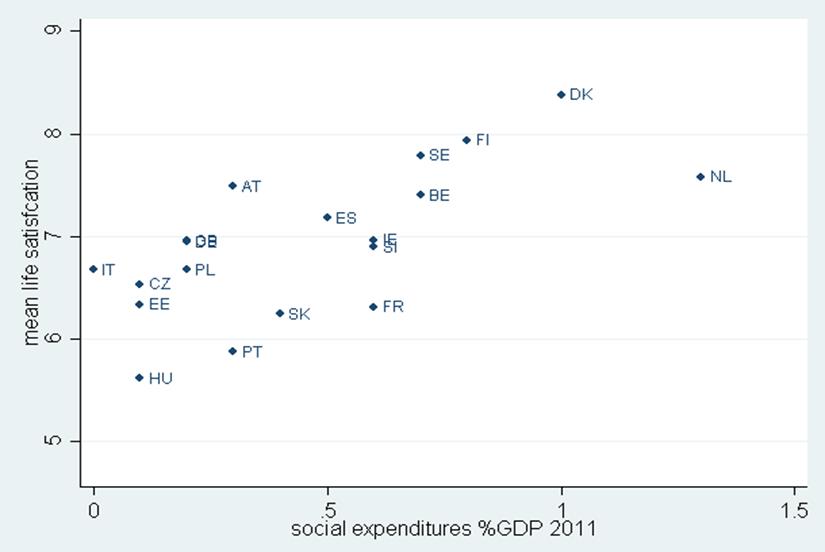

To illustrate the importance of welfare state policies – as also evidenced by the literature above – one can take a look at some plots showing a few policies and mean life satisfaction across countries (Figures 3 and 4). Due to space limitations, only one is shown here – on the relationship of social expenditures as a percentage of country GDP and subjective wellbeing (mean life satisfaction) reported in ESS (Figure 3). It is quite clearly that the existence of country clubs got reinforced in multivariate analyses. However, it is also notable that the position of some Central and Eastern Europe(CEE) or southern countries (e.g. Slovenia or Spain) is contrary to expectations or the vague welfare regime typology, seemingly sharing some features with more continental regimes. While Ireland and the UK – both representing the liberal, market oriented regime in the original classification – are further apart. Multivariate analyses – ordinary least squares (OLS) and multilevel models with various specifications and interactions – confirm these, but still welfare regimes or the generosity indicator stay always significant among explanatory factors.

Figure 3. Social expenditures as % of GDP and subjective wellbeing across EU member states.

Source: own calculations based on data from ESS 1-7 and OECD.

Out of the different macroeconomic and institutional context variables used in the analyses, the measure for the overall generosity of welfare states coming from the Comparative Welfare Entitlements Dataset (CWED database) (see Scruggs et al. 2014) always stayed positive and significant, just like welfare regimes, while active labour market policy (ALMP) expenditures in % of GDP were contradictory, and social expenditure were not necessarily significant on their own, but had moderating effects in interactions. Compared to Nordic countries, there is subjective wellbeing (SWB) penalty in all, i.e. liberal, Anglo-Saxon and continental regimes, but also in post-socialist CEE (where it is generally fairly low).

In terms of individual level factors, after controlling for several socio-demographic characteristics, unemployment is confirmed to be strongly negative especially for the life satisfaction of men, worst in liberal and southern regimes, whilst the effect of education (both the level and student-status) disappears after controls were introduced. Subjective general health strongly contributes to individual SWB of both sexes, but more for women; the same is true for social contacts, however it seems that living together with children in the household or no. of children is somewhat negative (though not significantly) for women, but not men.

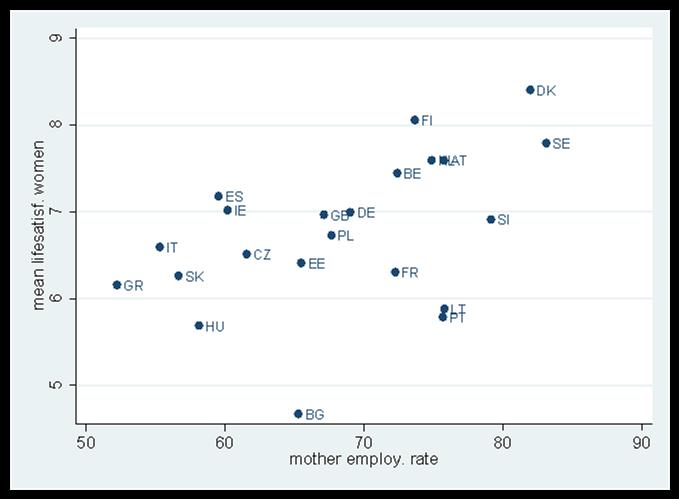

This leads to the need for further checking some gender norms and gender-specific variables, as it seems the devil is in the detail if one is interested in the female happiness puzzle. Figure 4 on maternal employment rates and female happiness reflects the different work-family regimes and their policy mix, which affects both.

Figure 4. Mean employment rate of mothers and women life satisfaction across EU member states.

Source: own calculations based on data from ESS 1-7 and OECD.

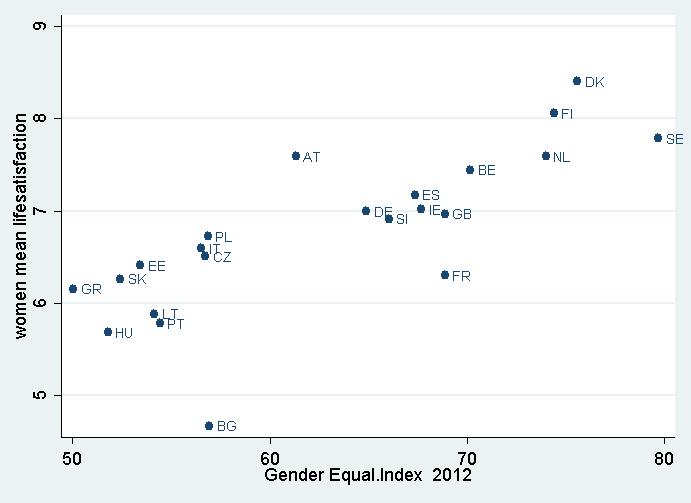

Indeed once the overall Gender Equality Index is introduced in estimations, it becomes clear how strongly significant and negative the effect of the Post-socialist and Southern welfare regimes become. This is also highlighted by Figure 5, with traditional gender norms still prevailing in these countries and their hybrid family-based policies (Korpi et al.2013; Boye 2011; Ferrarini-Sjöberg 2010), hard reconciliation of work and family that makes the situation especially hard for women, and thus their life satisfaction is somewhat lower than men in southern and eastern Europe (i.e. the female happiness puzzle is not true there). It is again notable however, that there is quite a diversity among CEE and southern countries, e.g. Slovenia is outstanding – whilst it is also clear that the other three regimes are closer, more levelling, with less difference along groups by activity or gender.

Figure 5. Gender Equality Index 2012 and women life satisfaction across EU member states

Conclusion

Even from this short snapshot, it is clear that not only is there a great variety of institutions, policies and macroeconomic, as well as social contexts (summarized as welfare regimes) across Europe that affect differences in wellbeing and its subjective perception across different countries, regions or communities; but also these different welfare state regimes, their policy generosity, policy solutions and reforms shape norms and incentives, shape informal and formal institutions, affect the economy and the web of society as well as individual outcomes. Thus it indeed matters a lot what work-family policy combo and service provision any given country applies, as this will not only affect individual choices and decisions about labor market participation, education and fertility (many of which are desired policy goals) and individual outcomes like income or happiness (as confirmed by this research), but also socioeconomic processes and even, for example, gender norms in the long run. Policymakers must be aware of such short and longer term consequences as well as the myriad different policy solutions and combinations they can select from.

Policy choices in this field too are context-dependent, one element brings or denies the other – there is no one size fits all solution to, for example female labour participation or fertility; althought there are, however, some win-win combinations – as reflected among others by higher female wellbeing figures. There is ample room for further research; however there are questions as to what is the best way, and with what source of data, so as to incorporate such policy effects and contexts into estimations on subjective wellbeing – especially when moving down to the sub-national level, where sample sizes and available data are smaller. Contributing to both the happiness and welfare state literature, as well as gender regimes, this research – that is, work in progress –provides at least some input for highly prioritized public policy themes and the measurement of social progress or inclusive growth; hence can perhaps help the future formulations of more effective and gender-aware policy interventions in labour market policies, family policies, social and education spending.

Acknowledgements

Judit Kalman acknowledges the financial support received from the RSA MERSA Grant scheme. You can contact Judit via judit.kalman@krtk.mta.hu

References

Alesina, A.; DiTella, R.; MacCulloch, R.J 2004, ‘Inequality and Happiness: Are Europeans and Americans Different?’, Journal of Public Economics, 2004, Vol. 88, p.2009 -2042

Bjørnskov, C., Dreher, A., & Fischer, J. A. (2007). The bigger the better? Evidence of the effect of government size on life satisfaction around the world. Public Choice, 130(3), 267-292.

Boarini, R. et al. (2012), “What Makes for a Better Life?: The Determinants of Subjective Well-Being in OECD Countries – Evidence from the Gallup World Poll”, OECD Statistics Working Papers, 2012/03, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k9b9ltjm937-en

Bohle,B.- Greskovits,B : Capitalist diversity on Europe’s periphery, Cornell University Press 2012

Boye, K. 2011Work and Well-being in a Comparative Perspective—The Role of Family Policy, European Sociological Review VOLUME 27 NUMBER 1 2011 16–30 16DOI:10.1093/esr/jcp051,

Clark, A. E. (2003), ‘Unemployment as a Social Norm: Psychological Evidence from Panel Data’, Journal of Labour Economics, 21, 2, 2003, pp. 323-351.

Clark, A. E. (2009), ‘Work, Jobs and Well-being across the Millennium’, IZA Discussion Paper No. 3940, January 2009, p. 44.

Clark, A. E. &Knabe, A. &Rätzel, S. (2009), ‘Boon or Bane? Others’ Unemployment, Well-being and Job Insecurity’, IZA Discussion Paper No. 4209, June 2009, p. 23.

Clark, A.E &Lelkes,O. (2005), ’Deliver us from evil: religion as insurance,’ PSE Working Papers halshs-00590570, HAL

Clark, A. E. & Oswald, A. J. (1994), ‘Unhappiness and Unemployment’, The Economic Journal, 104, 424, 1994, pp. 648-659.

Clark, A. E. &Frijters, P. & Shields, M. A. (2008), ‘Relative Income, Happiness, and Utility: An Explanation for the Easterlin Paradox and Other Puzzles’, Journal of Economic Literature, 46, 1, 2008, pp. 95-144.

Clark. A.E. & Claudia Senik, 2010. “Who Compares to Whom? The Anatomy of Income Comparisons in Europe,” Economic Journal, Royal Economic Society, vol. 120(544), pages 573-594, May.

Cooke, L.P. (2006). “Doing” gender in context: household bargaining and risk of divorce in Germany and the United States. American Journal of Sociology, 112 (2),442-472.

Di Tella, R. &MacCulloch, R. J. & Oswald, A. J. (2001), ‘Preferences over Inflation and Unemployment: Evidence from Surveys of Happiness’, American Economic Review, 91, 1, 2001, pp. 335-341.

Di Tella R., R. MacCulloch, A. Oswald, (2003), “The Macroeconomics of Happiness”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 85 (4), pp. 809-827.

EU DG Employment (2013) Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2013 http://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=738&langId=en&pubId=7684

Easterlin, Richard A.. 2001. “Income and Happiness: Towards a Unified Theory.” The Economic Journal, 111(473): 465-484

Easterlin, R. A., McVey, L. A., Switek, M., Sawangfa, O., & Zweig, J. S. (2010). The happiness–income paradox revisited. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(52), 22463-22468.

Esping-Andersen, Gøsta (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780069028573.

Eurofound (2016). The Gender employment gap: Challenges and Solutions, Publications Office of the European Union,Luxembourg

Ferrarini-Sjöberg 2010 Social policy and health: transition countries in a comparative perspective, International Journal of Social Welfare 2010: 19: S60–S88DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2397.2010.00729.x

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2005), ‘Income and Well-being: An Empirical Analysis of the Comparison Income Effect’, Journal of Public Economics, 89, 2005, pp. 997-1019.

Frey, B. S. & Stutzer, A. (2002), ‘Happiness and Economics’, Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002, p. 220.

Gornick, Janet C., and Marcia K. Meyers. 2003. Families that Work: Policies for Reconciling Parenthood and Employment. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Helliwell JF (2003). How’s life? Combining individual and national variables to explain subjective well-being. Economic Modelling 20(2): 331–360.

Kahneman, D. and Krueger, A. B. (2006) Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1), 3-24.

KORPI; W. Faces of Inequality: Gender, Class, and Patterns of Inequalities in Different Types of Welfare States, Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, Volume 7, Issue 2, 1 July 2000, 127–191, https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/7.2.127

Korpi, W., Tommy Ferrarini and Stefan Englund (2013) Women’s Opportunities under Different Family Policy Constellations: Gender, Class, and Inequality Tradeoffs in Western Countries Re-examined

Lalive, R., and Stutzer, A. (2010) Approval of equal rights and gender differences in well-being, Journal of Population Economics, Vol. 23, pp.933–962. Social Politics 2013 Volume 20 Number 1

McKee-Ryan, F., Song, Z., Wanberg, C. R., &Kinicki, A. J. (2005). Psychological and physical well-being during unemployment: a meta-analytic study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 53.

Meyers, M. K., Gornick, J. C. and Ross, K. E. (1999). Public childcare, parental leave, and employment. In Sainsbury, D. (Ed.), Gender and Welfare State Regimes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nieuwenhuis,R.Ariana Need, and Henk Van der Kolk2012. Institutional and Demographic Explanations of Women’s Employment in 18 OECD Countries, 1975 – 1999Journal of Marriage and Family 74 (June 2012): 614 – 630 DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00965.x

OECD [2015]: How’s Life?: Measuring well-being, OECD Publishing.

Ott, J. C. (2010). Good governance and happiness in nations: Technical quality precedes democracy and quality beats size. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(3), 353-368.

Pacek, A. C., & Radcliff, B. (2008). Welfare policy and subjective wellbeing across nations: An individual-level assessment. Social Indicators Research, 89(1), 179-191.

Rodriguez-Pose, A. – von Berlepsch, V. 2012. ’ Social Capital and Individual Happiness in Europe’, Brueges European Economic Research Papers 25/2012

Scruggs, L., Jahn, D., &Kuitto. (2014a). Comparative Welfare Entitlements Dataset 2. Version 2014-03. University of Connecticut & University of Greifswald

Senik,C.(2016), ‘ Gender Gaps in Subjective Wellbeing’, ENEGE Research Report for EC-DG Justice

Sjöberg,O.2010 Social Insurance as a Collective Resource: Unemployment Benefits, Job Insecurity and Subjective Well-being in a Comparative Perspective March 2010Social Forces 88(3):1281-1304 DOI: 10.1353/sof.0.0293

Stevenson, B., and Wolfers, J. (2009). The paradox of declining female happiness(No. w14969). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Stiglitz,JSen,AFitoussi, J.P. 2009 Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/118025/118123/Fitoussi+Commission+report

Veenhoven, R. (2000). Well‐being in the welfare state: Level not higher, distribution not more equitable. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 2(1), 91-125.