By Matt Finch, University of Oxford’s Saïd Business School, UK and Marie Mahon, National University of Ireland Galway, Ireland

How will Europe’s urban-rural balance shift in years to come? In times of uncertainty, when tomorrow may not look like today, how can researchers and decision-makers best explore future relationships and dynamics between regions? In addition, how can such speculations be related back to pressing questions in the here and now?

In this Research Hack, we share our experiences using scenario planning to explore the future of regional development in Europe, and answer the question: why are serious researchers spending time dreaming of futures which may never happen?

Can we re-IMAJINE territorial inequality?

The IMAJINE project is a European Commission-funded Horizon 2020 project investigating territorial inequality. Geographical dynamics mean that an individual in one region of the European Union (EU) may not enjoy the same income, living standards, or opportunities as an individual with a similar job and background in another region. The EU principle of territorial cohesion directs policymakers and institutions to reduce disparities between regions and prevent territorial imbalances.

IMAJINE asks, how are territorial inequalities currently measured? What alternatives are available? Is it useful to frame inequalities in terms of “spatial justice”: whether different places are treated fairly, and whether people’s ability to realise their rights is compromised by where they live?

Our researchers explore these questions through a multidisciplinary approach which brings together scholars, public sector stakeholders, and civil society actors. IMAJINE’s scenarios draw on this work to create plausible futures for European territorial inequality.

These scenarios are neither predictions nor expressions of desired future states for the EU. Instead, they present alternative assessments of the future context for IMAJINE’s key questions, challenging current assumptions in ways which are useful to the project’s stakeholders.

Unlearning and reframing: the power of scenarios

COVID-19 has reminded us that decisions do not just depend on the information at our disposal or our capacity for good judgment. They are also shaped by our ability to imagine the future that those decisions and their consequences will inhabit. As the Centre for Economic Policy Research’s Beatrice Weder di Mauro put it, when interviewed last year regarding the global impact of COVID-19, “There was no imagination to see where something like this could come from.”(1)

Scenario planning emerged during the Cold War, when strategists from the United States recognised that they could not plan for unprecedented nuclear conflict with reference to past wars. Herman Kahn (February 15, 1922 – July 7, 1983) and others used accounts of hypothetical future events to sharpen leaders’ thinking. Subsequently, executives at Royal Dutch Shell (commonly known as Shell, a Dutch multinational oil and gas company headquartered in The Hague, Netherlands) developed scenarios as a tool for corporate strategy.

As Rafael Ramírez and Angela Wilkinson state in Strategic Reframing: The Oxford Scenario Planning Approach (Ramírez and Wilkinson, 2016), scenario planning “invites explicit consideration and contrast of alternative future possibilities to frame and reframe a situation”.

In Ramírez and Wilkinson’s approach, scenarios are defined as assessments of the future context, developed for a specific purpose, that contrast with the way the future context is currently being framed.

These imagined futures create a unique vantage point from which to understand an issue or decision which we face. Factors which sit in the blind spots of current understanding can be “framed in” as a future scenario reveals their significance, creating the broader imaginative vista which Weder di Mauro found lacking in economists’ anticipation of a global pandemic.

George Burt and Anup Karath Nair argue that the benefits of reframing may include what is unlearned by using scenarios: “Letting go or relaxing the rigidities of previously held assumptions and beliefs, rather than forgetting them” (Burt and Nair, 2020). The safe space of an imagined future can allow contemplation of issues which might otherwise be too challenging or discomforting to address.

For IMAJINE’s work on territorial cohesion, that means offering visions of Europe’s future, which challenge current framings of territorial inequality and spatial justice – including the urban-rural balance. The scenarios enable critiques of contemporary aspects of social and spatial development that give rise to injustices and inequalities. In the process, they nourish thought on the potential shape of fairer, more emancipatory futures.

Building scenarios for the future of European regional inequality

IMAJINE’s four scenarios are grounded in the business environment of DG-REGIO, the Directorate-General of the European Commission responsible for regional and urban policy.

The research team developed a map of contextual uncertainties which might affect that environment: everything from oil prices and the degree of public trust in European institutions, to flood levels in Strasbourg, France, the official seat of the European Parliament.

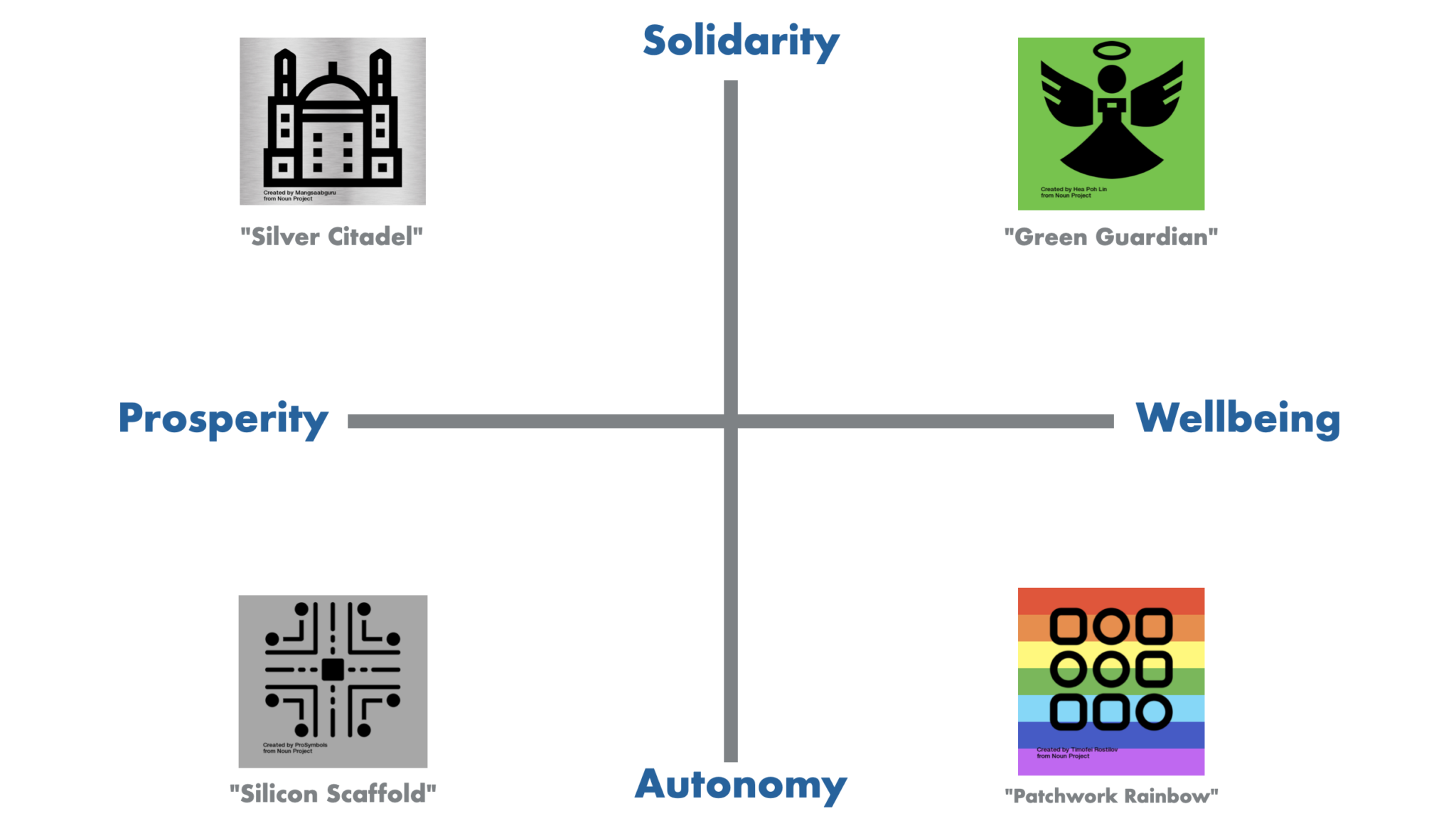

The team identified two key uncertainties which could be used to structure a scenario set: the degree of overall solidarity versus autonomy in EU policymaking, and whether the overall focus of European society was on economic prosperity or wellbeing.

Solidarity is a key concept underpinning EU territorial cohesion, with autonomy as a way to express concerns on spatial justice and perceived unfairness. Notions of prosperity suggest a greater emphasis on measures such as GDP, whilst wellbeing reflects more holistic measures of inequality. In the response to COVID-19, we have seen policymakers make these kinds of “wellbeing vs. prosperity” trade-offs as they weigh measures which may protect citizens while adversely impacting the economy.

Figure 1: IMAJINE Scenario Axes.

Source: IMAJINE Project’s Team

The two factors were placed on the axes of a grid, creating four scenarios characterised by combinations of solidarity versus autonomy and prosperity versus wellbeing.

These scenarios were elaborated by IMAJINE’s team in a series of workshops. Each draft was reviewed by external respondents with expertise across sectors including energy, sustainability, geopolitics, gender and sexuality, the media, and aerospace. Their comments helped us to build plausibility and flesh out the implications of each world.

DG-REGIO disburses regional development funds in seven-year planning cycles. Our scenarios were set in 2048, after four of these cycles have taken place: venturing far enough into the future that we would achieve a distinct vantage point from that offered by the assumptions of the present. The full scenario “sketches” that were issued to external respondents can be read online; we will merely summarise them here.

- In “Silver Citadel”, characterised by a high level of solidarity in policymaking and a focus on economic prosperity, regional inequalities were understood in terms of territorial variation in GDP, which was addressed via centralised policymaking augmented by advanced artificial intelligence.

- “Green Guardian”, the scenario characterised by high solidarity and a focus on wellbeing, saw the EU serving as the protector of sustainability in a climate-ravaged postcapitalist world where notions of ‘yield’ and ‘fair share’ replaced ‘profit’ and ‘net worth’. The old poles of urban-rural imbalance flipped, with Europeans fleeing crowded cities in fear of pandemics and coastal regions abandoned as sea levels rose: this was a future in which the Netherlands had been claimed by the waves, and Dutch climate refugees were scattered across Europe.

- In “Silicon Scaffold”, exploring the combination of a focus on prosperity with radical autonomy in policymaking, the EU existed in a weakened form, providing infrastructure for a highly digitalised world dominated by transnational corporations. The lines between government and business blurred, so that in this future a 2020s business location like “Tesla Brandenburg” came to serve as a ‘city-state’ in its own right. Some regions thrived thanks to their world-spanning corporate connections, but territorial inequalities were intensified and complicated in this world, as a non-territorial economy formed in digital space.

- Finally, “Patchwork Rainbow”, combining autonomy and wellbeing, saw a Europe where different regions embraced wildly varied and often conflicting values. In this future, the EU brokered the last talking shop for a patchwork continent, where regions could barely even agree on common standards of truth.

Each of these four scenarios stretched plausibility and challenged assumptions about how the future context in which regional development, including Europe’s urban-rural balance, would play out.

Putting the IMAJINE scenarios to work

Scholarship on urban-rural relations increasingly looks to what Jones and Woods (2014) and Brown and Shucksmith (2017) describe as place-based forms of ‘coherence’, both material and imagined; developing a coherent future vision that transcends traditional urban and rural categorisations. A precursor to this is the notion of ‘soft spaces’ (Brown and Shucksmith, 2017, 290) where collaboration with stakeholders happens more informally and experimentally. Scenario planning has a natural home in such spaces, providing scholars and stakeholders with a methodology to explore imagined futures and pathways.

IMAJINE’s scenarios are now being used with policymakers, institutions, and civil society actors across Europe. Users are invited to imagine themselves in each future and reflect on its implications: “How would we fare in such a world? How would that future look back on the choices we are making today? What signals are there in our own immediate environment that we are moving towards one or other of these scenarios?”

If spatial justice comes to mean equitable distribution of wealth by a centralised machine intelligence, what steps do urban or rural regional administrations need to take to ensure this aligns with their particular goals, values and priorities? What signs are there of such centralisation already? How might rural regions choose to accommodate requests from internal climate migrants to be granted refuge from pandemic-struck cities and flooded coastal areas? Will regionalist movements offer alternative governance models that can temper the potential extremes of wealth of the hypothetical city-state of ‘Tesla-Brandenburg’ with rural areas? What signs are there of such pitfalls already? In spatial justice terms, what does it reveal about attitudes to transfers of wealth?

The scenarios can serve to “wind tunnel” policy proposals for robustness and resilience, or to trigger new conversations about the future of fairness in regional development. They provide an intellectual sandbox to play with alternative notions of spatial justice and territorial inequality, to consider who might survive, thrive, or struggle in worlds characterised by these factors. It turns out that, properly deployed, the imagined future might be one of the most useful tools in understanding the rural-urban balance in times to come.

References

(1) Martin Sandbu, “Coronavirus: the moment for helicopter money“, Financial Times, March 10, 2021, accessed 29 May, 2021.

Brown, D. and Shucksmith, M. (2017) Reconsidering territorial governance to account for enhanced rural-urban interdependencies in America. Ann. Am. Acad. Soc. Polit. Sci., 672 (1) pp. 282-301

Burt, G. and Nair, A.K. (2020) ‘Rigidities of imagination in scenario planning: Strategic foresight through ‘Unlearning’’, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 153, p.119927.

IMAJINE (2021), Scenarios For The Future of European Spatial Justice – Expert Respondents’ Draft.

Jones, M., and Woods, M. (2014). New localities. Regional Studies 47 (1): 29–42.

Ramírez, R. and Wilkinson, A. (2016) Strategic Reframing: The Oxford Scenario Planning Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

About the authors

Matt Finch is an Associate Fellow of the University of Oxford’s Saïd Business School, where he teaches and serves as Lead Facilitator on the award-winning Oxford Scenarios Programme. He currently serves as a consultant to the IMAJINE project.

Marie Mahon is Senior Lecturer in Human Geography at National University of Ireland Galway. Her research interests focus on urban-rural change & development and on specific processes of change in rural communities. She is currently leader of the foresight component of the Horizon 2020-funded IMAJINE project.