Financialisation and urban densification: London and Manchester’s niche student housing markets.

DOI reference: 10.1080/13673882.2020.00001079

By Stefania Fiorentino, Nicola Livingstone, and Michael Short

In global cities, densification processes have frequently emerged as a rapid response to housing provision and longer-term urban sustainability. This Spotlight article discusses the wider implications of financialisation through densification processes, and specifically considers developments providing student accommodation, as an under-researched element of the UK’s housing market. We focus on ‘Purpose Built Student Accommodation’ (PBSA), drawing on evidence from London and Manchester. PBSA is framed as an alternative dimension of densification, one which is increasingly providing avenues for financialisation, and we use this piece as a provocation for further research on the topic.

‘Densification’ can be challenging to define due to subjective and myriad perspectives on how ‘density’ is understood. Adopted approaches in urban areas are frequently the cause of controversy. Densifying urban land can be construed as a sustainable approach to perpetuating the ‘compact city’, which encourages efficiency in managing resources such as land, energy and materials (Breheny, 1996) and can lead to the ‘creation of successful places’ (Tiesdell & Adams, 2012: 60). However, on the more negative flip side of this perspective, densification can be seen to split local communities, encourage gentrification and housing unaffordability (Immergluck & Balan, 2018), as a means of profit extraction for the developers and investors. So, does increasing density lead to increasing trends of so-called financialisation? Processes of financialisation – as a product of neoliberalism – reflect the dynamics of finance in contemporary capitalism, and can be defined as ‘the increasing dominance of financial actors, markets, practices, measurements and narratives at various scales, resulting in a structural transformation of economies, states and households’ (Aalbers, 2017: 544).

Literature on financialisation has highlighted the way the phenomenon has led to an inflation of housing prices, an oversupply of buildings and the deregulation of planning from the public to the private sector (Weber, 2015). Ultimately, such processes have undermined the essential right of providing houses and shelter to the wider population, that are intended as affordable places to live in relation to average wages and costs of living.

Notably less explored is the growth of private student housing facilities in the last decade, which actively contribute to densifying our city spaces, as land has been developed to provide for the burgeoning growth of student numbers in England across its largest cities: London and Manchester. Is densification through PBSA supporting processes of finanicialisation in the UK? Although PBSA serves a key purpose in providing temporary accommodation for students, as an asset it is an alternative type of housing, and a niche investment sector, which has become increasingly attractive to institutional investors in the last decade. It reflects a type of densification in cities which has received little scrutiny in terms of impact on investors, occupiers, localised housing markets and the wider urban economy.

This is somewhat ironic as the largest real estate transaction in 2020 so far, and reportedly the largest private transaction ever seen in the UK, has seen a portfolio of 69 PBSA properties (with almost 30,000 student units) exchange for £4.66bn, in a purchase by iQ Student (Blackstone) from Goldman Sachs and the Wellcome Trust (RCA, 2020). Included in this transaction were twelve PBSA developments in Manchester, primarily located around the University of Manchester, and fifteen across Greater London (RCA, 2020). This purchase illustrates how student accommodation is now becoming an institutional grade asset, with investors such as Blackstone expanding their PBSA portfolios. As an active equity fund, Blackstone has assets worth approximately £166.3 bn, across 725 markets in 35 countries, with the majority of capital in industrial (29%) and office property (30%) (RCA, 2020). To further demonstrate our point, in Manchester in the last five years the Unite Students REIT is the second largest investor across the city’s apartment sector, falling just behind Blackstone in terms of investment volume (RCA, 2020).

PBSA in the United Kingdom was also one of the most resilient and successful sectors for real estate development and investment in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). However, whilst the housing market crisis is consistently discussed in both the media and academic literature, the significant growth and impact of private student accommodation providers such as Unite students, Chapter and iQ, receive much less consideration. What was once a more alternative sector in the real estate market is now a more mature and institutionally appealing real estate investment. In Europe, the most remarkable case is London, where the densification through PBSA has visibly progressed alongside a steep population growth and an ongoing housing crisis.

Objective measures for defining residential density are provided through the London Plan (currently under review; GLA, 2016) density matrix and in Manchester’s Local Development Framework (adopted 2012), which provide indications of where densified development could be focussed, depending on accessibility, space efficiency and locational benefits. Local context clearly has a key role to play in densification debates, however the role of PBSA has expanded, as medium-high density developments provide amenities and accommodation in two of the UK’s most popular student destinations. However, concerns have been voiced which recognise that although students contribute economically and culturally to the cities, and require high-quality accommodation, such developments can be seen to potentially remove opportunities for the creation of housing and conventional homes (The Mayor’s Academic Forum, 2014). Moreover, indeed, PBSA itself needs to provide affordable and accessible lodgings for students. However, affordable for whom?

Census data show a 10% growth in the local population since 2005 in Manchester and 20% in London, with the population aged between 18 and 24 mostly stable in both cities since 2005 (ONS, 2020). Numbers tell us that London registers a total of 385,200 students against a total population of 8,962,000 (around 4.3% of the population). In Manchester, there are 117,900 registered students (4.1% of the total), with a total population of 2,835,700, which makes it the second largest student population in the UK (ONS, 2020). HESA reports that 21% of full-time students in London live in PBSA, as compared to a 26% in Manchester. Student numbers have grown around 3-4% since 2005, but after a steeper growth post 2008, the more recent growth patterns show a slowdown to pre-2008 values possibly due to the impact of Brexit. Nevertheless, planning strategies addressing student housing and promoting densification strategies are continuing assuming a constant growth in the student population and a growing need of PBSAs.

For example, the current London Plan (Policy 3.8 – Housing Choice) estimates the annual requirement of PBSAs assumes a 33% to 40% annual growth of full-time students to release pressure on conventional homes. Manchester Local Development Framework (2012: Policy H12) identifies student accommodation in the city centre as a tool for urban regeneration. The document specifies preferred locations for densification, and while warning against the potential for oversupply of bedspaces in PBSA, it suggests prioritising land for university halls, followed by PBSAs (preferred over HMOs). A more recent update of the document (2019) promotes PBSAs as a way to provide necessary student accommodation more quickly. Debates in cities such as Plymouth and Cardiff, reflect on how PBSA developments have helped to revitalise the local area and positively reinforce the importance of students to local economies, but raise concerns over the vulnerability of universities and market oversupply (Hale & Evans, 2019).

In England, densification processes and major developments aim to create value – for developers, investors and local authorities. For local authorities this is usually the result of a discretionary planning process where authorities extract negotiated contributions through the mechanism of planning obligations – Section 106 or the Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) – and paid by developers. Typically, through these mechanisms developers indirectly contribute towards local amenities, infrastructure and affordable housing units. However, contributions are the result of a process of negotiation based on several rounds of financial viability appraisals undertaken by the developer (Crosby & Wyatt, 2019). Viability appraisal mechanisms reflect this financially driven approach with landowners rather than communities often being the primary beneficiary of densification processes (Sayce et al., 2017). However, such perspectives do not preclude positive trickle-down impacts from developments and planning gain in local community contexts; impact is subjective and diverse.

The Benchmark Land Value is the suitable return set for the landowner and achieving this may result in the delivery of higher than expected densities, supported by the discretion of local planning authorities. Before the late 2000s local authorities did not assess the commercial viabilities of sites when setting planning guidelines and density standards (Colenutt, Cochrane, & Field, 2014). In the late 2000s, with the availability of cheap mortgages, riskier lending and the so-called “privatised Keynesianism” (Crouch, 2009), the neoliberal market dynamics have been expanded to the real estate market as a consequence of progressive processes of deregulation to reduce public investments even in the provision of affordable homes (Peck & Tickell, 2017).

The other issue to take into account when considering densification processes in London and Manchester is indeed the rise in the financialisation of real estate assets with their progressive commodification. The securitised interests provided by real estate and mortgages became, in the late capitalism, a way of investing money in a safe and tradeable way: transforming housing into an intangible asset with high tradable potential (Aalbers, 2016). Because of the underlining political and socio-economic variables, just like densification processes, the issue of financialisation is highly dependent from the surrounding spatial, temporal, and cultural framework. Urban investments in London are the result of a dense international network of interactions. The housing market has progressively attracted foreign direct investments becoming a safe deposit box for “the transnational wealth elite” (Fernandez, Hofman, & Aalbers, 2016). As well as luxury housing developments, is the development of PBSA in more dense cities supporting further international investment and financialisation processes?

The PBSA sector is clearly facilitating global investment. The global capital flows into PBSA in London from 2011 to 2017 accounted for £2.8 billion, mainly coming from North America (£1.5bn), followed by Europe and Russia (£700m), Middle East (£100m), and Asia Pacific (£500m) (JLL, 2017). In terms of costs, the average rent for a private sector en-suite (around 13 m sq.) is £154 per week in Manchester and £232 per week in London, 46% more than the average rent in the rest of the UK (Cushman & Wakefield, 2019). The average PBSA would accommodate around 500 students, but prices can vary a lot according to the amenities provided and the location. We have analysed the case of Unite group, the UK leading provider with assets in 27 cities. In London prices range from an average of £400 for a studio in Zone 1 in St. Pancras Way (including services like several common and private study rooms, a gym and outdoor terraces with panoramic view), to a cheaper £149 in North Lodge for an en-suite with 10 other flatmates in Zone 3 (shared kitchen and only one common room).

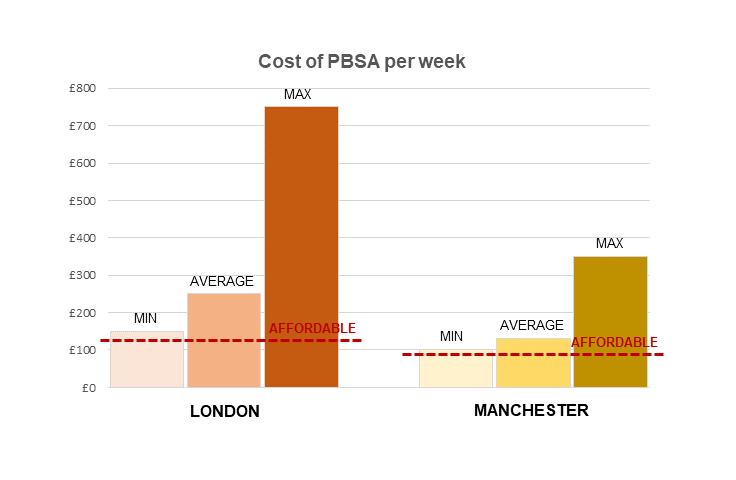

Figure 1. The chart shows average prices of PBSAs in London and Manchester (source: JLL, updated to 2019) as compared to the affordable rent per week calculated following the given planning standard updated to the current academic year.

In London over 200,000 students are unable to access PBSA, despite the sector having grown by 125% since 2007 with a further expected rental growth at 3-4% to be maintained until 2021 (JLL, 2017). These large-scale, dense PBSA blocks are clearly addressing a market need in both cities, although there is unsurprisingly a premium for London. However, it raises the question of who pays for the accommodation, and whether the costs make it unaffordable and potentially inequitable for students, combined with questions around viability and inflated land costs, as well as extractive processes of financialisation. Will the resilience experienced in the PBSA in the UK in recent decades continue following the burgeoning impacts of Brexit and the coronavirus?

In Manchester, Unite offers rooms from £99 (shared bathroom and up to seven flatmates), or £129 (en-suite, single bed) in the cheapest New Medlock House, to £202 for a classic en-suite or £225 for a studio in the more expensive Bridgewater Heights (closer to universities and better services). All prices are weekly. This is very different from what a full-time student can afford. The London Plan (section 4.17.7) defines the affordable rental cost for student housing as: “equal to or below 55% of the maximum income that a new full-time student studying in London and living away from home could receive from the Government’s maintenance loan for living costs for that academic year.” This would equate to £95/week in Manchester and £123/week in London. The highlighted examples would also explain why the student accommodation market in London and Manchester is undersupplied and still in demand, despite the planning compliance with growth and densification.

This article suggests that PBSA, is increasingly seen as an important investment asset for investment portfolios as being a counter-cyclical income stream that proves resilient when other real estate sectors may be experiencing cyclical downturns. University courses often see an increase in student numbers when unemployment levels go up and the wider economy is under pressure, which could be why student housing was so resilient following the GFC and potentially following the ongoing coronavirus crises. However, just like in the wider housing market the financialisation of PBSA is affecting their affordability and increasingly relocating the offer towards a prime sector. In London this is even more evident. For example, in Chapter’s Spitalfields (Greystar and Public Sector Pension Investment Board are among the shareholders) prices range from £269 per person per week for a 2 beds apartment (approx. £2150 per month) to £349 for an en-suite, £564 for a one bed studio, and £734 for a loft studio. All solutions offer the possibility of paying in instalments with 2% interest raise on each instalment. Additional amenities include: panoramic view, ground floor coffee bar, private study rooms, auditorium, on-site private gym and karaoke rooms. Here the luxury offerings are very clear and showing that PBSA is becoming something very different to the standard university accommodation, and only accessible to those students who are able to afford it.

Figure 2. Chapter Living student accommodation in Lewisham, London, part of the densification scheme for the area.

Global institutional investors have the weight of capital and the capacity to facilitate the development and longer-term investment into the PBSA sector in key university cities. Manchester and London are seen as strong and resilient markets with attractive yields and the potential for market monopolies. After all, large players seem to dominate the PBSA market, making financialisation processes more apparent. The current pandemic has further exposed the issue and the wider consequences of the financialisation of student accommodation, creating pressures on universities and their operation. However, some universities see the provision of accommodation by PBSA as one less cost for them to bear and operate, and often support the development of PBSA or enter into partnerships with providers, to counteract competition issues.

Further longer-term impacts in the aftermath of Covid-19 and post-Brexit are likely, but inherently uncertain. Looking at the geography of markets it remains to be seen whether this is a UK peculiarity or whether the trend is expanding to other world university cities. Will PBSA saturate the market, can such dense developments be adapted and reused for other purposes if necessary, for example co-living? At present, returns from PBSA are solid, but will we see more caution and concern for returns from investors over the future? PSBA is facilitating international investment and supporting densification processes. How will this continue to impact on the quality and operation of universities and on student numbers? Additional research is needed to address the universities perspectives and the occupier perspectives on the issue. Mainly to investigate what are the satisfaction rates and what moves a student to live in a private PBSA rather than in student halls provided by the university. The Brexit impact could actually be beneficial for international students as Sterling weakens, and the education and accommodation become cheaper due to exchange rate differences. Nevertheless, would this mean that the UK market is saturated for investors and they will move elsewhere? If so, just like in many other real estate sectors, a great challenge opens up for the years to come in re-structuring the current planning structure and re-inventing entire urban economic systems, within which financialisation is likely to remain a key influence.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to acknowledge that this research was supported by funding from the ORA, as part of an ongoing research project on ‘What is Governed in Cities’.

Bibliography:

Aalbers, M. (2016). The financialization of housing: a political economy approach. Abingdon: Routledge.

Aalbers, M. (2017) The Variegated Financialization of Housing. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(4): 542-554.

Breheny, M. (1996) Centrists, Decentrists and Compromisers: Views on the Future of Urban Form. In The Compact city: a sustainable urban form? 1st edition. Edited by M. Jenks, Elizabeth Burton and Katie Williams, 13-35. London/ Melbourne: E & FN Spon.

Colenutt, B., Cochrane, A., & Field, M. (2014). The rise and rise of viability assessment. Town and Country Planning, 84(10), 453–458.

Crosby, N., & Wyatt, P. (2019). What is a ‘competitive return’ to a landowner? Parkhurst Road and the new UK planning policy environment. Journal of Property Research, 36(4), 367–386.

Crouch, C. (2009). Privatised Keynesianism: An unacknowledged policy regime. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 11(3), 382–399.

Cushman & Wakefield (2019) UK student accommodation report 2019/20.

Fernandez, R., Hofman, A., & Aalbers, M. B. (2016). London and New York as a safe deposit box for the transnational wealth elite. Environment and Planning A, 48(12), 2443–2461.

Greater London Authority (GLA) (2016) London Plan. London: GLA.

Manchester City Council (2012) Manchester’s local Development Framework. Core Strategy 2012 to 2027.

JLL (2017) London Student Housing.

Hale, T. & Evans, J. (2019) Higher education: is Britain’s student housing bubble set to burst? Financial Times, 15th September 2019.

Immergluck, D. & Balan, T. (2018) ‘Sustainable for whom? Green urban development, environmental gentrification and the Atlanta Beltline’. Urban Geography 34(4):546-562.

Peck, J., & Tickell, A. (2017). Neoliberalizing space. Economy: Critical Essays in Human Geography, 475–499.

The Mayor’s Academic Forum (2014) Strategic planning issues for student housing in London. Mayor of London, London.

RCA (2020) Real Capital Analytics, Transactions database.

Sayce, S., Crosby, N., Garside, P., Harris, R., & Parsa, A. (2017). Viability and the planning system: the relationship between economic viability testing, land values and affordable housing in London.

Tiesdell, S. & Adams, D. (2011) Urban design in the real estate development process. Wiley Blackwell.

Weber, R. (2015) From Boom to Bubble: how finance built the new Chicago. The University of Chicago Press.

About the authors

Stefania Fiorentino is Senior Teaching Associate in Planning, Growth and Urban Regeneration at the University of Cambridge, Department of Land Economy and honorary lecturer to the Bartlett School of Planning (UCL). Before that she has worked between UCL and London South Bank University and she has previous working experience in international consultancies in planning and economic development. Her research interest focus on ways to reconcile planning and local economic development for more inclusive urban regeneration strategies.

Nicola Livingstone is Associate Professor in Real Estate at the Bartlett School of Planning (UCL). Nicola completed her PhD in Urban Studies at Heriot-Watt University before coming to work at UCL in 2014. Her research interests are interdisciplinary, spanning real estate, planning and social theory. Currently Nicola is involved in a European research project into residential investment flows, and her other research interests include densification processes and office market responses to the covid-19 crisis.

Michael Short is Principal Teaching Fellow in Planning and Urban Conservation at the Bartlett School of Planning (UCL). An urbanist and conservator, his work covers issues of design quality in planning and conservation processes. He has a particular interest in debates about increased building height and density in environments where heritage and character of place are relevant. He runs a studio on density with his MPlan City Planning students at UCL.