Recognising demographically declining areas in EU Cohesion Policy: a Case-Study of Multilevel Coalition Building

DOI reference: 10.1080/13673882.2021.00001102

By Serafin Pazos-Vidal, Head of Brussels Office of the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities, Belgium

Introduction

Demographic decline or depopulation are issues that have had in recent years wide currency both at national level (“Empty Spain”, “Brain Drain” in Eastern Europe, “Shrinking Cities” in Eastern Germany, the “France oubliée” of the “Gillet Jaunes”) as well as at EU level itself as shown by the appointment of a Commission Vice President for Democracy and Demography, due to the link between the decline of these “Places that don’t matter” (Rodriguez-Pose, 2018) and political extremism. However, this diversity of approaches has a direct impact on the way EU decisions and policies to address this issue are framed, or fail to be.

The Regulation of the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) 2021-2027 includes for the first time a definition of what is a territory affected by a demographic decline (provinces or municipalities with less than 12.5 inhabitants per km2 or that have suffered an interannual demographic decline of more than 1% during 2007-2017) and thus subject to receiving priority ERDF funding in the new programming period.

Drawing from the Actor-Centred-Institutionalism paradigm and the participant observation method, this paper provides a narrative of the genesis and eventual framing of the first-ever definition of what is a demographically declining area for the purposes of EU regional funding, as well as the potential and the limits of narrow ad hoc multilevel coalitions (as in Hooghe and Marks, 2003) aiming to influence EU decisions.

EU Cohesion policy response to Demographic Decline: a case of multilevel policy entrepreneurialism

The EU has previously considered the issue of demographic decline (e.g. the 2006 European Commission’s Communication and European Parliament’s Report, and under the present Ursula Von der Leyen’s Commission has a dedicated Vice Presidency), although this has not had materialised into specific EU policy interventions (in EU Cohesion or Rural Development Policy funding), save for the ad hoc funding arrangement for sparsely populated northern Finland and Sweden. Neither is there an EU-wide definition of what is a demographically declining territory, other than to allow certain state aid subsidies based on very population density (territories below 12.5 hab./Km2 population density). The Treaty on the Functioning of the EU only contains in its article 174 only contains a very general commitment for the EU to support those areas.

However, the Commission’s 7th Report on Economic, Social and Territorial Cohesion (2017) appeared to signal that, for the 2021-2027 EU budget programming period, the new generation of EU Cohesion Policy funds and Regulations would make their EU Structural Funds have demographic decline as a cross-cutting priority of the EU Structural Funds, precisely building on some of the above-mentioned academic cases (some of that at least indirectly supported by the Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy (DG REGIO) and specifically some of its senior officials e.g. the “Geography of (anti) EU discontent” (Dijkstra et al. 2018)). However, nothing came about in the draft proposals tabled in May 2018.

As a result of this, a small ad hoc coalition of Spanish actors (no more than a dozen involving territorial representatives – this author included -, a mayor and academically supported by like-minded EU officials and MEPs) mobilized to fill that gap, starting with crafting and lobbying a definition of what is a demographically declining territory for the purposes of targeting EU cohesion fund to those areas.

Their national affiliation is not accidental, as the so-called concepts of “Empty Spain” and “demographic challenge” are unique compared to other EU Member States, high in the Spanish policy domain (even having a dedicated Deputy Prime Minister), and public consciousness (del Molino, 2016). The two key proposals to influence the Commission’s thinking for the 2021-2027 period were drafted by Spaniards – Herrera Campo Opinion at CoR (2016) and Iratxe Garcia’s Report at the European Parliament (2017).

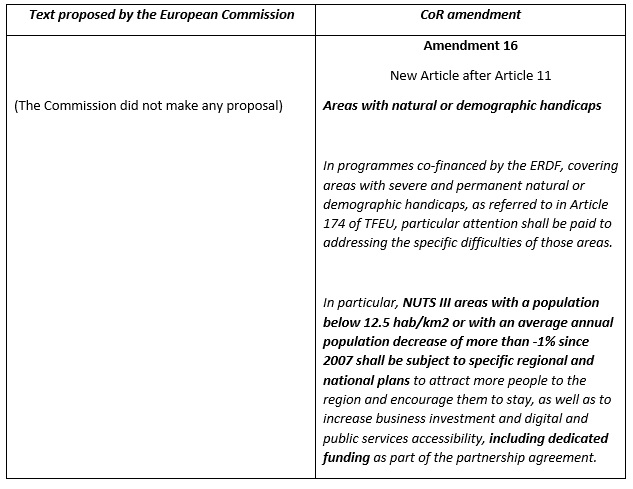

Making use of the Committee of the Regions (CoR) as an EU advisory role (yet a rather effective one in using its EU institutional embedding to act as a territorial policy entrepreneur to influence EU legislation (Piattoni and Schönlau, 2015)), the above mentioned small ad hoc group -this author included- suggested the CoR proposal on the European Regional Development Fund Regulation, the Rijsberman Opinion (2018) included the following definition:

Figure 1: The definition of areas with demographic haps

Source: Rijsberman CoR Opinion (2018)

This definition was a choice based on the existence of precedent and availability of data, hence the two complementary qualifying criteria: 12,15% hab/km2 is the criteria already used in state aid rules to support this kind of territories, and Eurostat NUTS3 level (mostly provinces, counties, départements in France) is where data is more reliable and widely available across the EU Member States. However, density is not the same as the decline in absolute population numbers, hence an alternative criterion was also added: the 1% annual decline over a period of time, as this is used already by geographical studies (in fact the map by Germany’s Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning and others from ESPON were specifically used as arguments of authority throughout this campaign). Overall an imperfect choice but one that was minimally robust against what was already expected to be a resistance from the Commission itself, and indeed the Member States and Regions (mostly classified as Eurostat NUTS 2 regions) themselves, who prefer continuity and were skeptical about further EU funding earmarks and too detailed policy direction being imposed from “Brussels” (i.e. the EU institutions based there). A sign of how ad hoc this coalition was is their inability to also replicate this definition in the ERDF Regulation also in the regulations of the other EU cohesion and rural funds.

With the support of the above-mentioned Garcia Perez (Socialist) and Valcárcel Siso (People’s Party), who were reassured by CoR’s endorsement in December 2018, this proposal then was tabled to amend the draft European Parliament ERDF negotiating position (Cozzolino Report, 2019). However, at least two other Spanish groups were at play, and Valcárcel Siso’s added yet other criteria (which was successfully voted in) of spatial targeting not only at NUTS 3, but optionally at Local Administrative Units (municipalities and groups of them), and that new criteria of 8 hab/km2 would be added on the basis that many Spanish provinces met at that territorial scale neither the density criteria nor the annual decrease one.

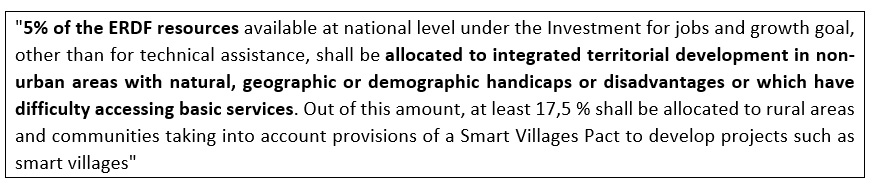

That expanded amendment was successfully voted in but, unexpectedly, the Parliament draftsperson (Andrea Cozzolino) added an even more ambitious clause, that of a 5% national earmark of ERDF funds to invest in policies against depopulation, mirroring the earmark that has long existed in the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) to develop non-farm local participatory investments (known as LEADER). Italy has a comprehensive strategy for its so-called internal areas hence the interest of receiving EU funding to support them.

Figure 2: ERDF depopulation ringfence

Source: Cozzolino Report (2020).

This package was officially voted as the EP negotiation position on ERDF, ostensibly because MEPs wanted to leave a popular legacy after the May 2014 elections, in the knowledge that it would be a new Parliament involved in the three-way negotiations (trilogues) with the Council of the EU (Member States) and the European Commission.

Thus, followed a long interregnum as a result of the European Parliament elections and the protracted selection of the Von der Leyen Commission, so by the time they started COVID-19 hit, negotiations were cancelled or delayed due to their virtual format, and the new Commission and Parliament were busy with the larger alternative to Cohesion Policy that is the new Next Generation EU. Furthermore, the creation of the first-ever EC Vice Presidency on Democracy and Demography shifted the attention away.

Taking all this together the chances of survival of the above-mentioned package through the many months of ERDF trilogues looked scant, if it were not for the original Spanish group. They approached yet another Spanish MEP, liberal Susana Solís, who as part of the Parliament negotiation team as “shadow Rapporteur”, mounted a significant resistance to scrapping the definition. The original group provided her with technical data (very often official data from the Commission itself) and arguments to keep the definition in the Regulation, in the wake of the Commission being openly (and publicly) skeptical, and the Member States resistant to being imposed new criteria and earmarks in the EU Cohesion legislative package.

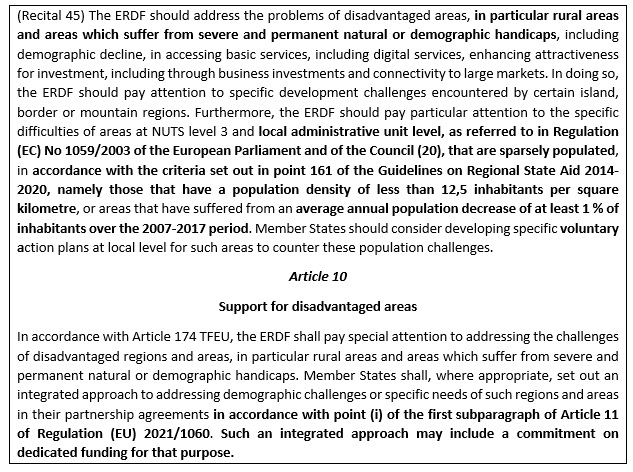

To avoid their veto MEP, negotiators accepted by September to scrap the 5% ERDF funding earmark, which was sacrificed on the basis that not all countries/regions suffer depopulation with the same intensity. Later in October, the definition of what is demographically declining was moved outside Article 10 of the Regulation up to the recitals, as ministerial negotiations considered that this would make it less binding.

To provide further reassurance to Member States and Commission, (and further ground for this new definition in precedent) the Spanish group suggested an explicit mention of the Regional State Aid rules for local areas with low population density. With all this, and not without strong insistence, this definition and supporting provisions were agreed upon in December 2020, making it into the final approved ERDF Regulation 2021-2027.

Figure 3. Demographic declining areas in ERDF Regulation (EU) 2021/1058

Source: Author´s elaboration.

Turning concepts into practice: the limits of multilevel coalitions and institutional resistance.

This protracted process of influence and sedimentation, led by a group (or constellation) of Spanish actors, shows both the potential of bottom-up, multilevel and territorial influencing of EU decisions, but it also shows the limits of a narrow ad hoc issue network has to have a lasting impact.

This is shown in the subsequent CoR opinions (2019, 2020); on the issue of depopulation, only token reference is made to this new definition as their focus is on individuals rather than territories (brain drain, aging), better reflecting the different approach towards depopulation in the eastern Member States (the rapporteurs were Karácsony from Hungary and Boc from Romania).

Any further reference to the new definition is the result of continued Spanish actors lobbying, lately belatedly being joined by Spanish regions as they were ironically not too warm to any mention of NUTS3 that might entail transfers of regional funding towards their provinces, (which belatedly came into view when mentioned to NUTS3, as in the Buda MEP report (2021) and the 2020 Employment EU ministerial Council conclusions of June 2020).

Despite this initial success at the EU level, the diverse set of non-cooperative Spanish actor coalitions involved in the above narrative also discouraged the Spanish Government (despite the remarkable media attention to this campaign in Spain) to even mention it in either its draft demographic strategy (2019) or in its new programme of 130 measures (2020) to be mostly financed via Next Generation EU.

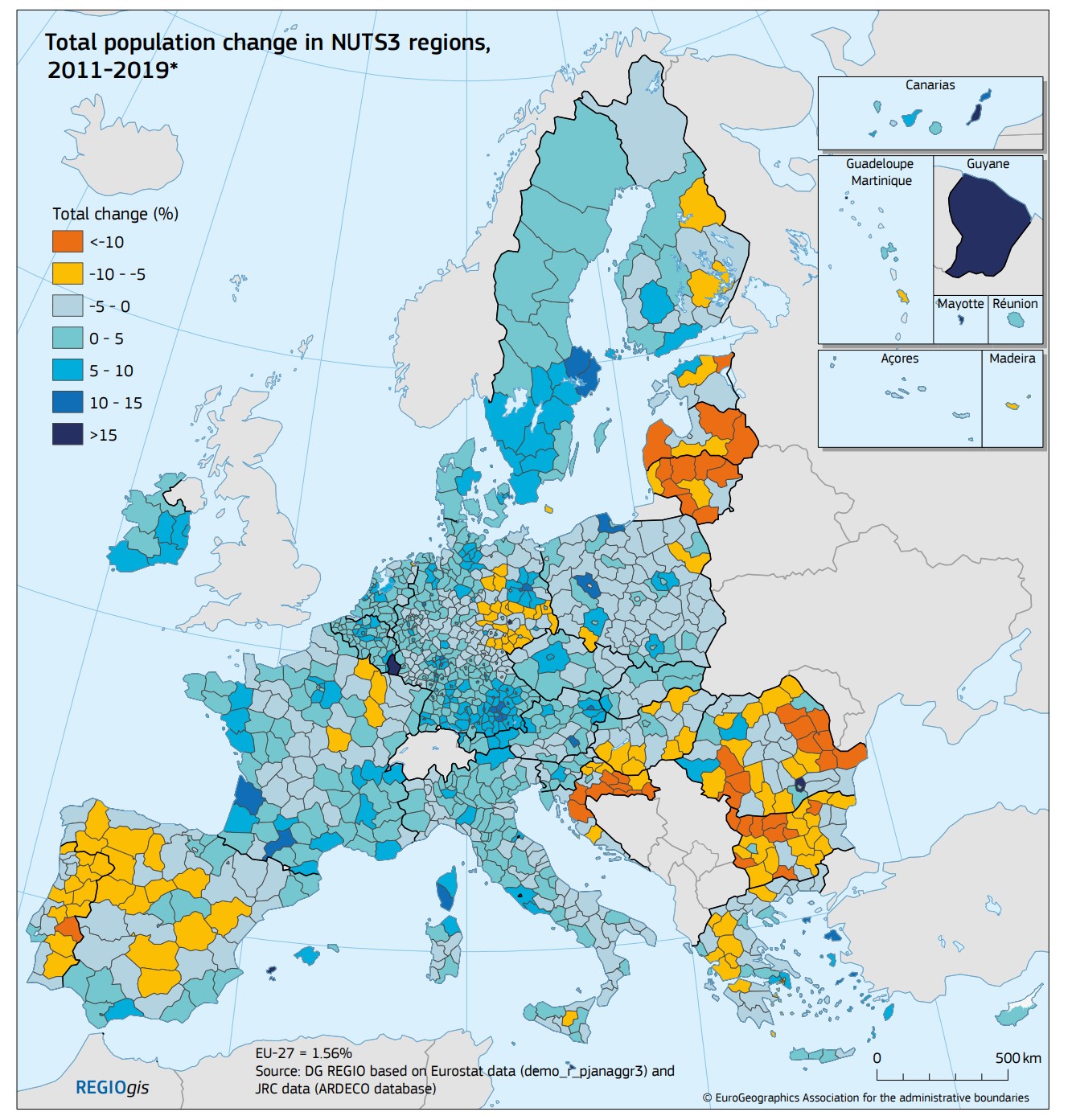

Map 1. Declining territories in EU27

Source: European Commission (2020: 21)

Equally the Commission is not enthusiastic about a definition it did not propose itself. The new guidance on using Structural Funds to tackle demographic decline will not use this new definition despite now officially included in the ERDF Regulation. Instead, it prefers to refer to the above-mentioned EU Council Employment ministerial conclusion. Ironically the new Just Transition Fund (a key proposal of the Von der Leyen Commission) uses a similar definition to regenerate declining territories with carbon-intensive industries which will allocate €17.5bn to NUTS3 regions, further highlighting the inconsistency of policy interventions between EU funds.

Most tellingly, despite the rising of the demographic issue in the EU agenda as signalled by the new Commission’s Vice Presidential position (led by former Dubrovnik mayor Dubravka Šuica) neither her sponsored Report on the ”Impact of Demographic Change in Europe” (EC, 2020), nor the long-awaited Communication, on a “Long Term Vision for the EU Rural Areas” (EC, 2021), make any reference to this new definition (though the 2020 report does use a rather similar one to illustrate the territorial impact of demographic decline, vid. supra). More widely in both documents, the role of EU Regional Policy (i.e. ERDF) only deserves a passing reference.

This contrasts with the consideration given to EU rural development policy concepts (e.g. “Rural Pact”, “EU Rural Action Plan” “rural proofing”, “smart villages”) included in the Long Term Vision document, despite the fact that ERDF non-farm investment in rural areas is much larger than that of EU rural development funding. This dispersion no doubt harms EU policy interventions in declining territories, regardless of which definition, if any, is used. Just as with the outside actors trying to influence the EU policies on depopulation, the same dynamics to frame and capture interests take place within the EU institutions themselves.

Conclusion

Framing this definition of demographic declining territories and getting it into EU legislation is a case in point of the contingent and transactional nature of EU decisions. The inbuilt resistance to formally recognise areas facing a structural decline in the very EU funding that were precisely created to address territorial disparities is highly revealing of the prevalence of multilevel rent-seeking and competing for ad hoc coalitions against the background of already established path dependencies and policy communities, both at EU and domestic levels.

The process that led to the recognition of such territories is also a case study of the very diverse domestic narratives of these “places that don’t matter” and how this affects influencing EU decisions.

It was also very revealing on the logic of collective action dynamics in that a small coalition of Spanish actors managed to exploit their available windows of opportunity within the EU institutional framework, but this also shows the limits of securing lasting impact in EU decisions if coalitions are not sufficiently wide to secure utility maximisation across the Member States and within the EU institutions themselves.

References

Del Molino, S. (2016) La España vacía: viaje por un país que nunca fue. Madrid: Turner.

Dijkstra, L., Poelman, H. and Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2018) ´The geography of EU discontent´, Working Papers. European Commission, WP 12/2018.

Hooghe, L. and Marks, G. , (2003) ´Unraveling the central state, but how? Types of multi-level governance´ American political science review, 97(2), pp.233-243.

Pazos-Vidal, S. (2019) Subsidiarity and EU Multilevel Governance: Actors, Networks and Agendas. Routledge.

Piattoni, S. and Schönlau, J. (2015) Shaping EU policy from below: EU democracy and the committee of the regions. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2018) ´The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it)´. Cambridge journal of regions, economy and society, 11(1), pp. 189-209.

About the Author

Dr. Serafin Pazos-Vidal is Head of Brussels Office of the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities. Academic researcher on multilevel governance, EU territorial cohesion, comparative territorial reforms. He is a member of the Regional Studies Association research network on EU Cohesion Policy. (Google Scholar profile; ORCiD).