By Crispian Fuller, School of Geography and Planning, Cardiff University, UK.

Introduction

In June 2016, 52% of the British population voted to exit from the European Union. Importantly, they did not vote for a particular exit agreement, but a rather a simple decision on whether to leave or not. The consequence of this and the May Government’s strategy of negotiating first with the EU, then presenting an agreement to Parliament, led to considerable political upheaval and a failure to pass this agreement into law. With the fall of the May Government, and subsequent Conservative Party election of Boris Johnson, a ‘no-deal’ Brexit has been conveyed by the new Government, much to the dismay of EU members. At the time of writing this, there remains considerable uncertainty regarding the final agreement, with a final attempt at resolving the Northern Ireland question still taking place. The importance of this contextual discussion is to illustrate the considerable uncertainty generated within the political realm, which has transferred into all aspects of British life, but most notably within the economic landscape! Of critical importance, in this regard, are the operations of foreign corporations in the UK. These in and of themselves are relational entities encompassing various forms of embeddedness within their home and host countries, and constant intracorporate and extra-corporate deliberations. Two critical aspects in this period have been subsidiaries experiencing impacts arising from pre-Brexit upheaval and uncertainties, and the corresponding need to mediate these conditions.

Intrinsic to the mediation of Brexit by subsidiaries and the impact of pre-Brexit upheaval and uncertainties is the actual role and status of the subsidiary within both the corporation and the global production network in which it is embedded. Here, there is a belief that subsidiaries with higher value-added production roles and responsibilities (i.e. ‘competence creating’), such as R&D, have greater importance to the corporation and significant autonomy and capabilities to respond, compared with subsidiaries with limited roles and capabilities (i.e. ‘competence exploiting’) (Cantwell and Mudambi, 2005). Subsidiary possession and access to specific capabilities (e.g. knowledge, skills) also strongly influences the nature of impacts, such as through those generated by way of other actors in global production networks. Subsidiaries are also ‘coupled’ with regions by way of the operation and geographies of the global production networks (GPNs) through which they work. Coupling denotes the extent to which global production networks, and corporations involved in these, are interdependent (Coe and Yeung, 2015). Coupling can range from ‘structural’ arrangements based more on low cost production and limited capabilities, to ‘functional’ arrangements where there can be stronger forms of interdependence through high value-added production. Change rather than stasis characterizes coupling, typically arising from the actions of corporations within GPNs, leading to processes such as decoupling (i.e. disinvestment and closure) and recoupling (i.e. reinvestment).

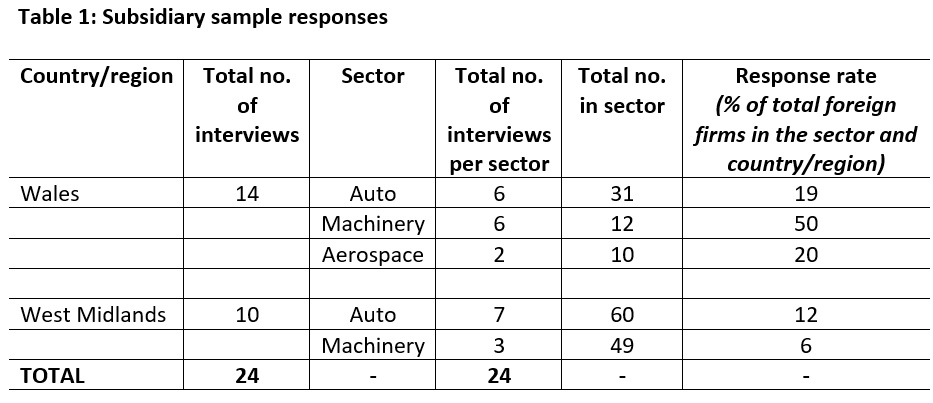

The purpose of this paper is to present results of an on-going study, funded by the Leverhulme Trust, into the impacts of pre-Brexit market and institutional upheaval and uncertainties on foreign-owned subsidiaries, and their mediation of these impacts leading up to a final agreement or a no-deal. The study examines the automotive, aerospace and machinery (SIC 26) sectors in the nation of Wales, and the English region of the West Midlands. These areas were chosen because of the prevalence and importance of these particular sectors in this region/nation, and because there are a range of competence creating and exploiting subsidiaries, accompanied by different forms of regional coupling. In total, 24 senior subsidiary managers, who have an active role in Brexit planning, were interviewed (See Table 1). Subsidiary case studies have been anonymized because of the intracorporate and market sensitivity of Brexit impacts and planning.

In what follows, the article will examine the: (1) impacts of the market and institutional upheaval and uncertainties arising from the Brexit vote, and on-going negotiations up to September 2019; and, (2) the mediation of these conditions, and the planning for various exit trading agreements, by subsidiaries. The main conclusions of this research are that the Brexit vote and negotiation process has, for the vast majority of subsidiaries, led to various negative consequences, and these impacts occur both within host regions and other regions involved in global production networks. Second, considerable resources have been diverted to mediating potential final Brexit agreements, reducing future capabilities, and potentially negatively impacting the nature of regional ‘coupling’ in the future.

The impacts of the Brexit vote and negotiation period on foreign subsidiaries

There have been a considerable number of surveys and media reports on the impacts of Brexit on various economic sectors corporations, with particular impacts relating to supply chains and investment (CIPS, 2019). What is critical about the impacts of Brexit on foreign subsidiaries is that, as with all companies, they are having to address forms of institutional upheaval and change that they have never encountered before. Institutions are essentially in place to produce economic and social stability, reducing uncertainties through various institutional means (e.g. legal contracts, regulations), to ensure confidence, security and certainty in economic and social life. The Brexit vote, and the problematic preparations for exit, have produced wide-ranging tangible and intangible negative impacts on foreign subsidiaries. The basis of rapid institutional change characterised by instability is for the creation of uncertainties that are generated when it is unclear what institutional forms will supersede those being replaced. For individual subsidiaries, the intangible consequences of this are substantial, not least because they are experiencing uncertainties that have produced and/or amplified broader, more tangible impacts. Subsidiary managers generally take the view that while Brexit will produce negative consequences, particularly for just-in-time supply chains in the manufacturing sectors, they could mediate this if they were aware of the final trading agreement. As they are not, the impacts of Brexit up to this point have been compounded because they are unsure of what countermeasures should ideally be undertaken. In the case of the automotive sector, this has led to c.£500m of additional spend on Brexit planning (SMMT, 2019).

Supply chain impacts

There have been significant cost pressures through the global production networks in which subsidiaries are working. Indeed, the implications of substantial institutional change in one country are such that impacts travel through global production networks and the regions in which elements of supply chains are located. The most common instance of this are the effects of the currency fluctuation of Sterling, making imports of components costlier for the automotive and machinery subsidiaries, resulting in cost-cutting measure such as redundancies. In other instances, the mainland European customers of subsidiaries have reduced orders for fear of a lack of supply or bottlenecks at the customs borders in ports. Even large OEMs, such as a global cable manufacturer in Wales, with considerable market power in terms of supply chain spend, has experienced first tier suppliers refusing to provide extra inventory, with the subsidiary manager noting that while Brexit is of critical concern for UK firms, it is far less important for mainland European suppliers serving a number of countries. Subsidiaries have faced extra costs relating to requests by suppliers for additional risk management procedures to be put in place, a trend that is notable across subsidiaries with different value chain positions and capabilities. In one particular example, a subsidiary in the aerospace sector has had to risk manage supply through the possibility of using air travel to ensure supply chains are maintained.

Further costs have related to the extra costs for stockpiling, returning to a production model of just-in-case during the lead up to the first exit date of the 31st March, a process that began again as 31st October approaches. This has characterised all manufacturing case study subsidiaries, with many reporting between a 20-25% increase in stocks, representing the crystallization of efforts to reduce uncertainties arising from a potential no deal Brexit. In one particular example in the machinery sector, the subsidiary has stockpiled an extra £200k worth of stock for the 31st March 2019 deadline, out of an annual stock budget of £900k, representing a 22% increase. The regional implications are for an increase in economic benefits where suppliers are located across mainland Europe leading up to the two Brexit deadlines, but with reduced demand between these the deadlines as subsidiaries work through their stocks.

Investment impacts

Arising from uncertainties around the final agreement, the majority of subsidiaries in all sectors have witnessed the decline or postponement of investment decisions by corporate HQs. Resources have instead been devoted to Brexit planning, typically around the worst case scenario of no-deal, a process which began with the 2016 vote. As one first tier subsidiary supplier manager notes: “It’s hard work convincing Head Office to even look at the UK at the moment because, you know, all they will see are the headlines. The headlines just scream uncertainty, and as we all know, uncertainty is the enemy of business” (author’s interview). This conforms to broader business surveys that report a considerable decline in firm investment, and particularly that in the manufacturing sectors (CIPS, 2019). Further factors producing declining corporate investment relate to concern around reducing consumer demand, both as a response to Brexit, but also concern at the possibility of a recession across Europe.

The impact of Brexit are interwoven with much broader market trends and corporate decision-making, particularly in relation to the automotive sector. The existence of OEMs producing automobiles in the UK is a fundamental condition for the sector. There has been declining outputs of cars at these OEMs for some time, with the likes of Honda down to 130,000 to 140,000 cars per year, with a belief that you need around 200,000 per year to ensure strong profitability (author’s interview). This forms part of a much broader cyclical trend in the automotive sector, with the highest UK car manufacturing and sales in 2017, but having been followed by a downward trend, particularly in relation to the reduction in diesel car sales. Automotive subsidiary managing directors in the West Midlands and Wales believe this will take place over a four to five-year period, while production adjusts to market demand, and new hybrid and electric cars are introduced, but that this requires considerable OEM investment in European OEM sites.

Such trends have been significantly compounded by Brexit. On the one hand, Brexit is a major issue for foreign subsidiaries in the UK, with these broader trends of secondary importance in the short term. On the other hand, their corporate HQs view Brexit as aggravating these medium to long term market and institutional changes. Future investment by the OEMs across the UK will be very much dependent on a favourable trade agreement that maintains just-in-time systems. Up to this point in time, the corporate HQs of first and second tier automotive suppliers have typically postponed investment in UK subsidiaries, and in certain cases are diverting investment to subsidiaries in European regions. The longer term consequences of this are that since 2016 capabilities (e.g. technologies, machinery, skills) have not been developed to attract future rounds of investment as new products are introduced for hybrid and electric cars. Such processes have negatively affected both competence exploiting and creating subsidiaries, but with the latter far more dependent on investment in capabilities, suggesting that the roles of Wales and the West Midlands automotive GPNs are also likely to be negatively affected in the future. Going forward, the introduction of the EU-Japan free-trade deal in 2019 will see import tariffs on cars reduce to zero, meaning that the attractiveness of reshoring production to Japan has increased for certain OEMs, potentially leading to disinvestment and closure.

Subsidiary mediation of the Brexit vote and negotiation period

In contrast to the uneven Brexit planning taking place in SMEs across the UK, and given the considerable uncertainty since 2016, a characteristic of all subsidiaries (both competence creating and exploiting) in the study has been Brexit planning focusing on the worst case scenario, namely a no-deal Brexit where trading terms revert to WTO principles and tariffs. Through such processes there has been a substantial reconfiguration of costs and capabilities, from one based on the EU regulatory regime, to one focused on a no-deal trading framework. This represents substantial extra costs as the basis of no-deal planning is to ensure continuing production and value creation. Nonetheless, it is generally viewed by subsidiary managers in terms of an ‘indemnity’ to be written off in the event of a trading agreement taking place, but which has been characterised by considerable intracorporate deliberations with HQs. A further aspect of this is to balance this short term viability, by way of measures to ensure continuing viable production at subsidiaries, with the long term viability of a subsidiary in the UK, based on the ability to create value in the future. In the context of the uneven and problematic negotiation of a final agreement in 2019, such efforts have proven to be challenging for subsidiary managers. As explored below, such efforts will potentially have a significant impact on Wales and the West Midlands in the future, but this is likely to be very uneven. Going forward, competence creating subsidiaries possessing specific capabilities are in a stronger position in which to attract further investment and maintain their corporate roles.

Short term viability has involved a focus on contingency planning with suppliers and customers in the manufacturing sectors in Wales and the West Midlands. The most publicized aspect to this has been stockpiling of inventory, a material manifestation of the need to risk manage uncertainties. This has led to significant front-ending of subsidiary spending before the Brexit deadlines in March and October 2019, and boosting profits for GPN suppliers in mainland European and Southeast Asian regions. There are significant limits in terms of the amount of components that can be stockpiled for certain firms. Mainland European suppliers have struggled to produce extra amounts because of increasing demand as part of this stockpiling, while efforts at reshoring can only contribute to fulfilling certain component requirements, since certain UK-based suppliers have been inundated with orders. Competence creating subsidiaries, requiring higher value-added components, have particularly struggled with this, since there are a lack of suitable suppliers in the UK. This compares with competence exploiting subsidiaries that work through more hierarchically organized production networks.

A further critical aspect has been the deliberation around how long potential disruption will last in the case of a no-deal Brexit, and what stockpile levels will be required. The actual space available determines the amount of stock held, with the vast majority of subsidiaries reporting that very little space is available. On the other hand, subsidiary managers have cognitively constructed particular temporalities about how long potential disruption will occur, typically informed by three monthly financial reporting temporalities. Yet, in reality, they have had very little insight into how long any disruption will actually last. Stockpiling has therefore not been a straightforward exercise for subsidiaries in the manufacturing sectors.

Maintaining existing, rather than re-configuring, supply chains have tended to be prioritised by subsidiary managers, suggesting that existing regional economic links are being maintained, and that the degree of change to production networks and regional coupling is limited at this time. This is largely because of the substantial costs associated with introducing new suppliers, including the need for due diligence to ensure they can supply at suitable levels of quality and quantity. Mediation of Brexit upheaval by way of global production networks has therefore been heavy constrained, representing neither offensive (e.g. new investment) or defensive (e.g. cost cutting) restructuring, but the continuation of a status quo during a period of significant institutional and regulatory upheaval. This adheres more broadly to the desire of managers of competence creating subsidiaries (where autonomy is evident) and corporate HQ managers with greater influence over competence creating subsidiaries, to maintain stability with suppliers whilst institutional and market instabilities occur.

Longer term efforts at ensuring the viability of subsidiaries has tended to be of lesser importance, in both types of subsidiary. What we have seen is the prioritization of issues and tasks based on the immediacy of their impact, such as in stockpiling. Moreover, the considerable subsidiary resources devoted to Brexit planning has diverted resources away from investment plans, such as in new technologies and operational processes. This includes expanding existing capabilities in logistics and regulatory compliance working on the basis of a potential no-deal. Only a minority of subsidiaries have pursued new market opportunities within and beyond the EU, as well as, in the case of OEMs, looking at re-configuring their production networks to beyond the EU.

What this represents is not ‘passive downgrading’ (Blazek, 2015), but efforts at ‘stasis’ and ‘stability’ at a time of uncertainty. In the present context, therefore, we are not witnessing the declining ‘value capture trajectories’ of subsidiaries, characterised by disinvestment and potential closure. However, as emphasised by Szalavetz (2016), an important dimension of corporate restructuring is the effects of longer term strategic planning, in that actions within the present context have important temporal impacts in the future. For manufacturing sectors, and especially for the automotive sector, investment has to be continuous in order to maintain market competitiveness. Yet this has not been the case for these subsidiaries, meaning that when coming to the end of particular product life cycles, there is the potential for investment to go elsewhere in the corporation where capabilities are much stronger, thus producing regional decoupling. Only in the case of three subsidiaries, all operating in the machinery sectors in the West Midlands, is there overt investment in capabilities as a means in which to fulfil expanded and new roles, and generate greater value capture. While operating within different machinery sub-sectors, and having disparate global production roles, they are subsidiaries that have experienced continuous levels of growth, possess significant corporate autonomy, and have access to strong regional capabilities, most notable, highly skilled engineers and low cost semi-skilled workers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Brexit has produced significant uncertainties for foreign subsidiaries operating in the automotive, aerospace and machinery sectors in Wales and the West Midlands. The immediacy of maintaining stability has meant that there is considerable stasis in these sectors and regions. On the one hand, such efforts are significant as they seek to reduce potential disinvestment and closure. On the other hand, there are important temporal dimensions that will only be manifest in the future, as corporate HQs potentially closure subsidiaries and decouple from regions where capabilities are lacking. The future is thus potentially one of a major economic disruption and change to existing regional institutional path dependencies, but where new forms of path creation will depend on decisions that have been made in the present.

This research will funded as part of a Leverhulme Trust Fellowship on ‘Brexit, foreign corporations and regional development’ (RF-2018-195\7).

References

Cantwell, J. and Mudambi, R. (2005) MNE Competence-Creating Subsidiary mandates. Strategic Management Journal, 26, : 1109–1128.

Blazek, J. (2016) Towards a typology of repositioning strategies of GVC/GPN suppliers: the case of functional upgrading and downgrading. Journal of Economic Geography, 16: 849–869.

Coe, N., Yeung, H. (2015) Global Production Networks: Theorizing Economic Development in an Interconnected World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply (CIPS) (2019) The Brexit Storm. London: CIPS.

Society of Motor Manufacturer and Traders (SMMT) (2019). UK Automotive Trade Report. London: SMMT.

Szalavetz, A. (2016) Post-crisis developments in multinational corporations’ global organizations. Competition & Change, Vol. 20(4) 221–236.

About the author

Dr Crispian Fuller, Senior Lecturer in Economic Geography, School of Geography and Planning, Cardiff University. His research centres on the examination of urban politics and governance, and the organisational geographies of corporations, particularly in relation to global production networks.