Between Liberty and Regional Leviathan: Establishing engagement with Local governance in Leicestershire.

DOI reference: 10.1080/13673882.2018.00001015

By Martin Quinn, University of Leicester, UK.

Regional Studies Association early career grant holder, Martin Quinn employs classical social contract theory to interpret the success of efforts made by local government and governance institutions in Leicestershire to engage with local business and the wider community to deliver economic growth.

:Introduction:

The UK economy is generally acknowledged to be one of the most unbalanced in the developed world (Pike & Tomaney 2009, McCann 2016) with the bulk of private sector investment taking place in London or the Greater South East. Successive Governments have tried to address this through a series of sub-national interventions with limited success. This article discusses some of the initial findings from research funded by a Regional Studies Association Early Career Grant. In which, I use social contract theory to explore the efforts made by local government and governance institutions in the City of Leicester and County of Leicestershire in England to engage with their local businesses and communities. The inspiration for this research came from the Regional Studies Association conference in Izmir in 2014, where some friendly fire from a Geographer concerning the relative contributions scholars from geography (theory) and political science (case studies) make to our field of study, got me thinking about how I could use classical political theory in my own work.

Why social contract theory?

I turned to Social Contract theory to investigate (the lack of) engagement with sub-national institutions and policies in England. England’s political traditions draw on the principals of liberty and limited government espoused by enlightenment philosophers such as J.S. Mill (2010) and Bentham (2010). Social Contract theorists, such as Hobbes (1996), Locke (1980) and Rousseau (1993), explore the conditions that are required for populations to submit to political authority (Boucher & Kelly 1994), usually at the level of the Nation State and most famously expressed in the form of Hobbes’ ‘Leviathan’. My work argues that regions in England need to show they are able to bridge the gap between liberty and leviathan by reconsidering the work of Rousseau and Locke – i.e. if a regional leviathan could be seen to provide the conditions for liberty laid out by Mill et al then the populous would be prepared to sign a social contract with it. This article outlines some of the initial findings on what those conditions might be.

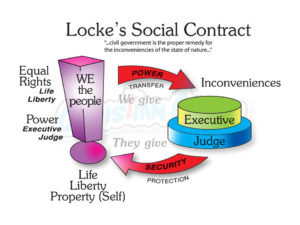

The research uses two particular takes on social contract theory, firstly from the work of John Locke, who outlined the things the State needs to offer to form a social contract with its population (Figure.1). Locke identifies security and protection of liberty and individual rights as being key to persuading people to willingly give power to a Government. One of the aims of this research is to reimagine the diagram below for sub-national engagement.

Figure 1: John Locke’s Social Contract. (Source: Democracy Chronicles)

The second take on social contract theory that I use comes from Rousseau’s work on the idea of ‘independent man’ and how authority needs to persuade them that they need to comply with rules. In the Geneva Manuscript of his social contract theory Rousseau writes:

“… ‘I admit that I do, indeed, see that this is the rule which I can consult; but I still do not see,’ out independent man will say, ‘the reason for subjecting myself to this rule. It is not a matter of teaching me what justice is; it is a matter of showing me what interest I have in being just’…” Rousseau, Geneva Manuscript Chapter Two, (cited in Lloyd Thomas 1995)

For the purposes of this research I treat the local business community as ‘independent man’ and the ‘rule’ as the economic development plans of the local governance structure. It is not enough to show local businesses that you have a plan as an economic development officer or City leader, you also need to demonstrate that they have a stake in those plans and strategies work in their interests.

Leicestershire as a Site for Research

Leicester has undergone a remarkable transformation over the past decade and is an ideal location in which to explore the concept of a social contract at a sub-national scale. The Economist cited Leicester as having some of the fastest business growth rates in the UK outside of London and the governance structure first established by a Multi Area Agreement in 2008/9 has given the local economy a stable platform from which to develop through the Local Enterprise Partnership. The City has one of the few Elected Mayors in England and turnout at both elections to date (41% in 2011 and 59% in 2015) has been impressively high. The Local Government arrangements are complex and have the potential to cause some confusion with a Unitary Authority for the city, a two-tier structure of District Authorities and a County Council alongside hundreds of Parish Councils. At a slightly larger regional scale the City and County were once part of the remit of the now defunct East Midlands Development Agency and are now formally included in the strategic planning of the Midlands Engine initiative, although this research found little evidence of engagement with the Midlands Engine plans. For this research 50 in depth interviews were carried out with a range of key stakeholders from across Leicester and Leicestershire representing members of the various Local Authorities, the Mayor’s team, the Local Enterprise Partnership, local businesses and community groups.

Engaging Business

When considering business engagement the research assessed the situation from two angles – firstly what did the governance institutions need to offer in order to gain the buy in and engagement of the local business community, and secondly, what form might that engagement take. The second of these was an attempt to put some flesh on the often used phrase of ‘business led policy’, which policy makers and politicians use to give credibility to their policies without really explaining the roles available to business.

The economic development strategies created in Leicester and Leicestershire were developed in close collaboration between the Mayor, the City, County and District Councils and the Leicestershire Local Enterprise Partnership (LLEP). From the outset, the governance plans consulted widely with the local business community, something that was very much appreciated by respondents from the private sector. Part of the strategy involved recognising the need to treat start-ups and established businesses separately. The City built and launched a number of start-up and business accelerator facilities including the Leicester Creative Business Depot (LCBD), which is based in the Cultural Quarter of the city centre. LCBD offered new tech and creative businesses affordable office space in the city centre and access to a business mentoring scheme, where more established businesses could offer advice and support. The local authorities’ willingness to facilitate these networks rather than dictate how they ran was seen as crucial in building their credibility and trust in the economic development plans being developed.

“…create a network to help people meet each other. So it’s a bit more hands off. It recognises that the ideal purpose of a public sector should be to say I’ve got your back, rather than to say I’m going to lead you.” Private Sector Respondent 2018

At the other end of the scale the LLEP and the City worked together to attract blue chip companies into the City. A prime example was the relocation of IBM into office space in the city centre, a move that involved one of the local Universities, De Montfort, producing large numbers of computer science graduates to fill the new job opportunities being created. This and other developments were greatly helped by the decision making powers afforded to the Elected Mayor, Sir Peter Soulsby, who was able to take quick decisions backed by both the resources and power to get things done. This came across in several interviews as a positive for the city and business engagement.

“I’ve always found Peter Soulsby to be somebody who makes quick decisions. ..And I’ve always liked that about him. I’ve felt, compared with previous leaders he’s been like, right, let’s do it… And that’s an entrepreneurial spirit.” Private Sector Respondent 2018

Moving back to Locke’s social contract model (Figure.1), we can see that in order to create the conditions for business engagement at the lower tier it is crucial that speed of process and evidence of power to act are visible assets of local governance. The other crucial factor is the relevance of the geography involved. It was clear both from this set of interviews and my own previous research (Quinn 2013) that businesses in Leicester and Leicestershire were prepared to get involved with the plans of the LLEP because they could see a direct link to their own economic prospects. This is something that was absent at the wider East Midlands during the period of the Regional Development Agencies in England and even the current Midlands Engine initiative. Returning for a moment to Rousseau’s independent man, businesses could see both the ‘rule’ in the LLEP plans and the logic for them taking an active role in it.

In Figure 2, I present an initial attempt at redrawing the social contract diagram in Figure 1 as a social contract for local business engagement. As discussed above, the three crucial factors for gaining buy-in are speed of process, power to act and the right geography. In return for these, businesses in Leicester and Leicestershire were happy to offer their time and knowledge, to feed into the development of strategic economic plans for the City and County and also to publicly support these initiatives once announced, thus lending their credibility to new developments. In addition, they were also happy to give their time to mentoring new businesses in facilities such as the LCBD and other accelerators such as ‘Dock’ and ‘Makers Yard’.

Figure 2: A Social Contract for Local Business Engagement

Community Engagement

The other aspect of this research was concerned with community engagement with local government and governance. Turnout in local elections is notoriously low in England and yet both elections so far for the elected mayor position in Leicester have seen turnouts significantly higher than for similar positions around the country – 41% in 2011 and 59% in 2015 compared to between 29-33% for the raft of elected metro mayors in 2017. The decision to introduce an elected mayor position to the City was a controversial one, especially as, unlike in other cities in England, the move was not subject to a local referendum. However, once the first election had been held a number of public meetings were held to outline the new role and introduce the new team in charge of the City.

“We introduced ‘meet the mayor’ sessions, which were held in the city centre and across the city. I was very keen that… certainly in that first six months or so, we had to capitalise on the newness of everything. That was the time really. … there was a very very short window in my view …to establishing the roles in the eyes of the public, and to try to secure that understanding.” Public Sector Respondent 2018

“the eyes of the public were able to try to separate, you know, this sort of political identity of the mayor and his leadership team away from the sort of, the very well established impression people had of, you know, in inverted commas, of ‘the council.’” Public Sector Respondent 2018

The mayoral role, as well as being attractive to the business community, had an additional impact on local democracy. Previously City Council leaders were chosen by the ruling party in the Council and had to answer to them rather than the public to keep their position, the move to Mayor gave the public a direct role in choosing the head of the City authority. Once elected, the Mayor embarked on a very public campaign of carrying out 100 pledges in the first 100 days in office to further emphasise the power and scope of the new role as Leicester’s figurehead. Away from the Mayor, local councillors across the City and County hold regular public ward meetings and are increasingly active on social media platforms to increase their connection to their constituents, both individually and through community groups and leaders. Leicester is one of, if not the, most ethnically diverse Cities in England, with a non-white population of 49.48% at the time of the last census, well on track to be the first City in England with a majority non-white population. As a result of this the City Council has long developed community engagement strategies which bring together the leaders of the various, disparate, community and religious groups in the City and this has helped to shape a culture of collaboration among the different groups with each other and the Council.

Another key finding that emerged during this phase of the research was the, sometimes hidden, role played by Parish Councils and community groups (the latter were largely located in the City as unlike most of the County the City is not Parished) in local engagement. In a, sometimes confusing, two-tier system it is not always clear which tier deals with which issues, although both the Districts and the County said they acted as referral points when issues not under their remit were brought to their attention. Following on from another round of Government funding cuts the County Council was faced with the decision to close some 36 local community libraries. Instead of outright closure the County worked closely with the Parish Councils to reposition them as community assets run by local committees of volunteers determined to keep their local library open. This move saw use of the space occupied by the libraries increase and increased overall engagement with local issues amongst the community.

Conclusions

This article has outlined some of the emerging findings from research using social contract theory to investigate engagement at the sub-national tier in England. Of particular importance here was the territory – Leicester and Leicestershire have strong identities and both people and businesses clearly saw the link between themselves and the governance structure. Secondly the local government institutions made concerted efforts to include local people and business in the development of their strategies and have been able to demonstrate their ability to get things done adding to their credibility and increasing the willingness of people and business to get involved.

References

Bentham, J., 2010, Bentham: A Fragment on Government, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Boucher, D. & Kelly. P., 1994, The Social Contract from Hobbes to Rawls, Routledge, London

Hobbes, T., 1996, Leviathan, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Lloyd Thomas, D.A., 1995, Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Locke on Government, Routledge, London

Locke, J., 1980, Second Treatise of Government, Hackett Publishing Co, Indiana, USA

McCann, P., 2016, The UK Regional National Economic Problem, Routledge, London

Mill, J.S., 2010, On Liberty, Penguin, London

Pike, A. & Tomaney, J., 2009, The State and Uneven Development: The Governance of Economic Development in England in the Post Devolution UK, Cambridge Journal of Regions Economy and Society 2 (1) pp 13 – 34

Quinn, M., 2013, New Labour’s Regional Experiment: Lessons from the East Midlands, Local Economy 28 (7/8) pp 738 – 751

Rousseau, J.J., 1993, The Social Contract and the Discourses, Everyman, London