By Dra. Ana Gutiérrez Sanchis, Researcher at Francisco de Vitoria University and Dra. Laura Gómez García, Professor at Francisco de Vitoria University, Madrid, Spain

1. Introduction

Security is a global challenge that affects the population. Population growth is increasing quickly in urban areas, where insecurity and its perception arise from the interplay of social, economic, and cultural factors that disrupt social cohesion and heighten the perception of risk. Spatial polarization in cities can concentrate criminality in specific areas due to left-behind places, poor public lighting and low levels of public investment, perpetuating social exclusion and fostering illicit activities (Wacquant, 2008; Moser, 2004; Sheptycki, 1997). Furthermore, pronounced economic crises, terrorism alert states or attacks exacerbate collective vulnerability, further increasing the sense of insecurity (Martínez Paricio, 2007). Also, some emergencies related to health can generate a feeling of insecurity among citizens (Huesca, 2022). Some examples in recent years are the COVID-19 pandemic and the scabies outbreak in Alcala de Henares (Madrid, Spain). Other types of emergencies like environmental disasters or fires can influence on security as well.

For this research, it is very important to consider that Casa de Campo is the biggest forest park in Madrid, with 1535.52 hectares. For an international comparison, Central Park in New York has 341 hectares. Casa de Campo is an area declared an Asset of Cultural Interest since 2010 as Historical Heritage (B.O.C.M., 2010). This statement establishes a protective environment that safeguards the Site History of possible environmental and urban conditions that may alter its uniqueness or undermine its landscape values.

This article considers Global Challenges like environmental issues, immigration, and organized crimes (such as drug trafficking, other crimes against public health, or human trafficking and smuggling), which are the leading known hotbeds of crime in the Lucero neighbourhood, at the Latina District in Madrid (Spain). Other crimes in the Lucero neighbourhood are shown in the crime maps, which will be explained.

2. Literature Review

Countries like the United Kingdom publish through the British Police their criminological map with some objective security data in maps. They are responsible for making this kind of publication online with objective security data, which enhances transparency and informs public policy. The British Police’s detailed crime reports, absent in Spain, demonstrate improved public perception and institutional trust (Quinton & Tuffin, 2007). Such initiatives promote an accurate understanding of crime and encourage citizen participation in prevention strategies (Innes, 2004).

This official and virtual criminological map is not made in Spain. Nevertheless, the 3 Criminological Atlas of Madrid made with official data provided by the Police were elaborated by Dr. Felipe Hernando Sanz (Hernando Sanz et al., 1999; Hernando, 2001).

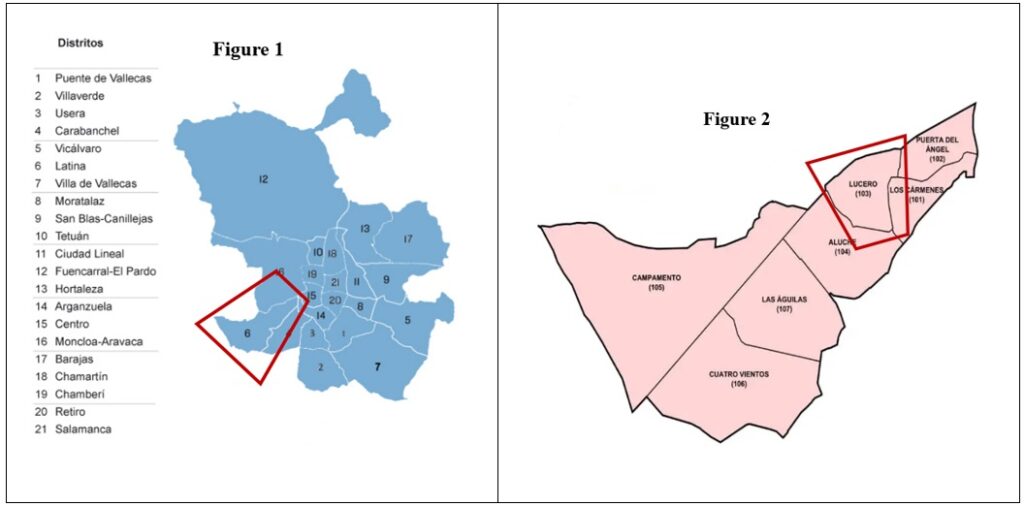

The city of Madrid is divided into 21 administrative districts (see Figure 1), and the area for the case study is the Lucero neighbourhood (see Figure 2), located in the Latina District, southwest of Madrid city.

Figures 1 and 2. Map of the city of Madrid by districts (Figure 1) and Map of the Latina district by neighbourhoods (Figure 2)

Source: City Hall of Madrid.

3. Methodology

These results are part of the previous pilot project in the Batan neighbourhood (2021-2022) and the current project, “Measuring the perception of insecurity, victimization, and fear of crime in the Lucero neighbourhood (Madrid).”

The main goal of this article is to present the Virtual Criminological Maps of the Lucero neighbourhood and surroundings.

The specific objectives are:

- Visualizing crime patterns and victimization. The data could only be collected through newspapers and social media information. Still, some of them were obtained through fieldwork, making victimization questionnaires, which is the only way to have access to some information of crimes due to Official Spanish Police data being difficult to access.

- Identifying high-crime areas, such as Batán-Casa de Campo and Cullera Street, to guide future policy interventions.

Another crucial scientific contribution is the new crime typology, which uses its codification to develop an international and unified crime typology. This typology improves the current one developed by the Ministry of Interior (Government of Spain) with the National Statistics Institute.

The inspiration for creating a new crime typology with codification is based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), a global standard for recording health information and causes of death. The ICD is developed and updated annually by the World Health Organization (WHO). Recently, another new Historical International Classification for Diseases (ICD10h) was created under the Cost Action European Project GREATLEAP (Reid et al., 2024).

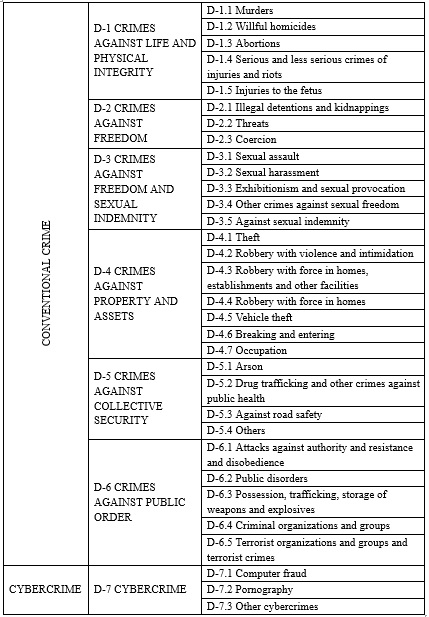

The new codification and typology of crimes (see Table 1) created is based on the Crime Balance by the Ministry of Interior and the Statistics of Convicts of the National Institute of Statistics.

On the crime map, they are classified into seven sections:

- Crimes against life and physical integrity (D-1): murders, willful homicides, serious and less serious crimes of injuries and riots, abortions and injuries to the fetus.

- Crimes against freedom (D-2): illegal detentions and kidnappings, threats and coercion.

- Crimes against sexual freedom (D-3): sexual assault, sexual harassment, exhibitionism and sexual provocation, sexual indemnity and other crimes against sexual freedom.

- Crimes against property and assets (D-4): theft, robbery with violence and intimidation, robbery with force in homes, establishments, and other facilities, vehicle theft, breaking and occupation.

- Crimes against public safety (D-5): arson, drug trafficking, and other crimes against public health, road safety, etc.

- Crimes against public order (D-6): Attacks against authority, resistance and disobedience, public disorders, possession, trafficking, and storage of weapons and explosives, criminal organizations and groups, terrorist organizations and groups and terrorist crimes.

- Cybercrime (D-7): Computer fraud, pornography and other cybercrimes.

Table 1. New codification and Typology of crimes

Source: Based on the National Statistics Institute (INE) and Crime Report (Ministry of Interior), 2023.

This research focused on creating a crime map of this neighbourhood and its surroundings using newspaper data. Media communication also significantly reinforces the perception of insecurity (Silva & Guedes, 2023; Huesca, 2022) and provides information that police, emergency services, victims, witnesses, and neighbours use for crime prevention.

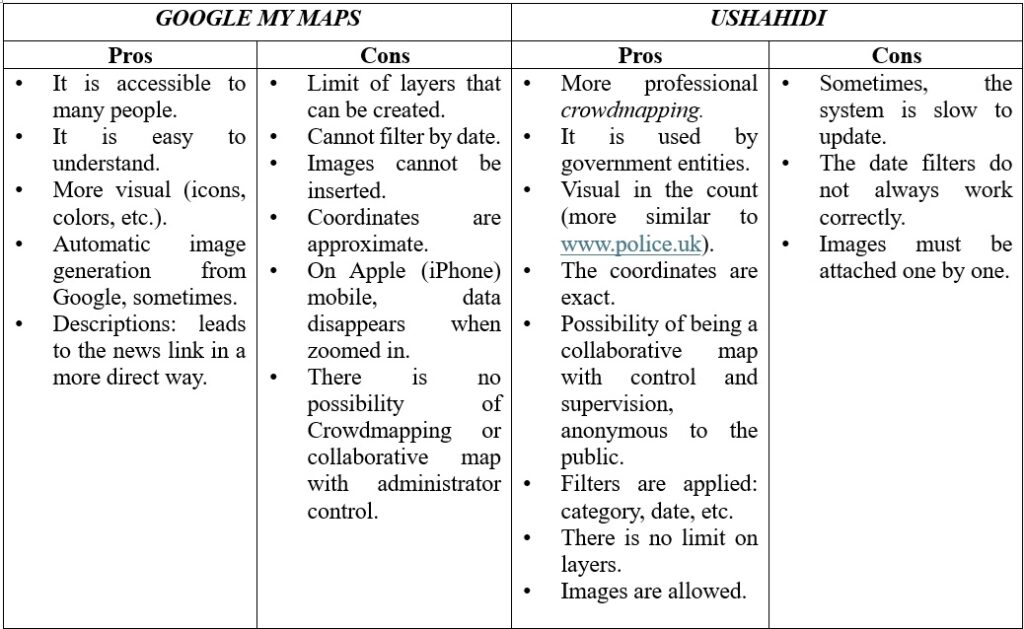

In Table 2, there is a Comparison of Geographical Tools between Crowdmapping and Virtual Maps, with comments of pros and cons for each geographical tool. Ushahidi is a good geographical tool for crowdmapping. It could be used to research the dark figure of crime, providing authorities with precise information for targeted interventions. This innovative approach integrates public participation into crime prevention and policymaking, advancing the understanding of local security issues. By fostering community engagement and transparency, the study enhances citizen awareness and the effectiveness of public security measures.

Table 2. Pros and cons Comparison of Geographic Tools: Crowdmapping or Virtual Maps

Source: own elaboration.

4. Results: Virtual Crime Maps in the Lucero neighbourhood and surroundings

The study introduces the criminological maps accessible via Google Maps and Ushahidi, offering a tool for citizens to visualize crime data. We can see that the Lucero neighbourhood, which is in the Latina District, is one of the most populated districts in Madrid.

There are two known hotbeds of crime:

- It is close to Batan-Casa de Campo, where the crime rate increased by 611% in 2020 after the Richard Schirrmann Youth Hostel became a Centre for Unaccompanied Minors. Some arson happens, as it is illustrated in the virtual criminological maps.

- The other is in Cullera St., Madrid’s largest drug-trafficking hub. It is a place left behind by authorities, evidencing the lack of public policy action. These dynamics push residents to leave the place, selling their houses below market price or adopt self-protection measures, reflecting a perceived lack of institutional protection (Jackson & Gray, 2010; Chataway & Hart, 2019).

Lucero is the only neighbourhood in Madrid to have had fixed National Police devices in recent years.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study combines principles of environmental criminology and crime geography by creating crime maps that enhance access to information. Available on Google Maps and Ushahidi, these tools significantly contribute to the Geography of Crime in Madrid. Its interactive and digital nature allows for future citizen involvement, enabling individuals to report crimes, even those not officially recorded.

We conclude that improving security requires public policies tailored to the neighbourhood’s needs, blending community-driven interventions with infrastructure enhancements. This initiative informs the public and equips authorities with precise data for more effective decision-making, laying the groundwork for a replicable model in other urban neighbourhoods facing similar challenges.

The Virtual Criminological Maps, accessible via Google Maps and Ushahidi, are a key tool for visualizing and analysing crime patterns. They can encourage citizen participation, allowing users to report crimes and uncover the dark figure of unreported incidents. This approach mirrors successful international initiatives, such as in the UK, where publishing objective security data enhances public trust and institutional transparency (Quinton & Tuffin, 2007; Innes, 2004). By integrating digital tools and fostering collaboration between citizens and authorities, the study offers a replicable model for other urban neighbourhoods, aiming to improve perceptions of security and public policies, ultimately contributing to safer and more cohesive communities.

6. REFERENCES

Abdullah, A., Hedayati Marzbali, M., & Bahauddin, A. (2015). Broken windows and collective efficacy: Do they affect fear of crime? SAGE Open. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2158244014564361

B.O.C.M. (2010). Decreto 39/2010, de 15 de julio, del Consejo de Gobierno, por el que se declara Bien de Interés Cultural, en la categoría de Sitio Histórico, la Casa de Campo de Madrid., Boletín Oficial de la Comunidad de Madrid, No. 275. https://diario.madrid.es/cieacasadecampo/wp-content/uploads/sites/61/2020/10/BIC.BOCM-20101117-5.pdf

Chataway, M. L., & Hart, T. C. (2019). A social-psychological process of “fear of crime” for men and women: Revisiting gender differences from a new perspective. Victims & Offenders.

Hernando Sanz, F. J., Bosque Maurel, J., & Universidad Complutense de Madrid Facultad de Geografía e Historia Departamento de Geografía Humana. (1999). Espacio y delincuencia : atlas criminológico de Madrid (1983-1997) [Dissertation].

Hernando Sanz, F. J. (2001). Espacio y delincuencia. Consejo Económico y Social.

Huesca González, A. M. (2022). El sentimiento de inseguridad en los ciudadanos, producto de la realidad que transmiten los medios. El ejemplo del COVID-19. Madrid: Tirant Lo Blanch.

Innes, M. (2014). Signal crimes and signal disorders: Notes on deviance as communicative action. The British Journal of Sociology, 55(3), 335-355.

Jackson, J., & Gray, E. (2010). Functional fear and public insecurities about crime. The British Journal of Criminology, 50(1), 1-22.

Martínez Paricio, J. I. (2007). Seguridad e inseguridad en la opinión pública de la Unión Europea. Observatorio de Seguridad. Ayuntamiento de Madrid.

Moser, C. O. N. (2004). Urban violence and insecurity: An introductory roadmap. Environment and Urbanization, 16(2), 3-16.

Quinton, P., & Tuffin, R. (2007). Neighbourhood change: The impact of the National Reassurance Policing Programme. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 1(2), 149-160

Reid, A., Garrett, E., Hiltunen Maltesdotter, M., & Janssens, A. (2024). Historic cause of death coding and classification scheme for individual-level causes of death – Codes. Apollo – University of Cambridge Repository. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.109961

Sheptycki, J.W.E. (1997). Transnational Policing and the Makings of a Post-modern State. Trends Organ Crim 2, 100–101 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02901640

Silva, C., & Guedes, I. (2023). The role of the media in the fear of crime: A qualitative study in the Portuguese context. Criminal Justice Review.

Wacquant, L. (2008). Ordering insecurity: Social polarization and the punitive upsurge. Radical Philosophy Review, 11(1), 1-12.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to acknowledge the contribution of the academic institutions, collaborative researchers and internships that made this research contribution possible, by Francisco de Vitoria University, Complutense University of Madrid and Comillas Pontifical University. Last but not least, to the State Security Forces, Private Security Personnel, and Health and Emergency Services.